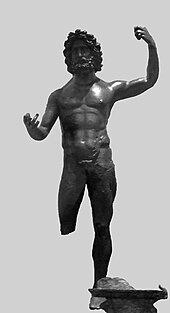

Jupiter (god)

His identifying implement is the thunderbolt and his primary sacred animal is the eagle,[8][9] which held precedence over other birds in the taking of auspices[10] and became one of the most common symbols of the Roman army (see Aquila).

When Marcus Manlius, whose defense of the Capitol against the invading Gauls had earned him the name Capitolinus, was accused of regal pretensions, he was executed as a traitor by being cast from the Tarpeian Rock.

[22] Jupiter was served by the patrician Flamen Dialis, the highest-ranking member of the flamines, a college of fifteen priests in the official public cult of Rome, each of whom was devoted to a particular deity.

As the senate did not accede to the proposal of a total debt remission advanced by dictator and augur Manius Valerius Maximus the plebs retired on the Mount Sacer, a hill located three Roman miles to the North-northeast of Rome, past the Nomentan bridge on river Anio.

It was Valerius, according to the inscription found at Arezzo in 1688 and written on the order of Augustus as well as other literary sources, that brought the plebs down from the Mount, after the secessionists had consecrated it to Jupiter Territor and built an altar (ara) on its summit.

The amnesty was granted by the senate and guaranteed by the pontifex maximus Quintus Furius (in Livy's version) (or Marcus Papirius) who also supervised the nomination of the new tribunes of the plebs, then gathered on the Aventine Hill.

[41] A dominant line of scholarship has held that Rome lacked a body of myths in its earliest period, or that this original mythology has been irrecoverably obscured by the influence of the Greek narrative tradition.

[44] Jacqueline Champeaux sees this contradiction as the result of successive different cultural and religious phases, in which a wave of influence coming from the Hellenic world made Fortuna the daughter of Jupiter.

Tarquin's wife Tanaquil interpreted this as a sign that he would become king based on the bird, the quadrant of the sky from which it came, the god who had sent it and the fact it touched his hat (an item of clothing placed on a man's most noble part, the head).

[74] This competition has been compared to the Vedic rite of the vajapeya: in it seventeen chariots run a phoney race which must be won by the king in order to allow him to drink a cup of madhu, i. e.

Romans themselves acknowledged analogies with the triumph, which Dumézil thinks can be explained by their common Etruscan origin; the magistrate in charge of the games dressed as the triumphator and the pompa circensis resembled a triumphal procession.

Linguistic studies identify the form *Iou-pater as deriving from the Proto-Italic vocable *Djous Patēr,[7] and ultimately the Indo-European vocative compound *Dyēu-pəter (meaning "O Father Sky-god"; nominative: *Dyēus-pətēr).

[130] To the same atmospheric complex belongs the epithet Elicius: while the ancient erudites thought it was connected to lightning, it is in fact related to the opening of the rervoirs of rain, as is testified by the ceremony of the Nudipedalia, meant to propitiate rainfall and devoted to Jupiter.

[151][152] In a similar manner one can explain the epithet Victor, whose cult was founded in 295 BC on the battlefield of Sentinum by Quintus Fabius Maximus Gurges and who received another vow again in 293 by consul Lucius Papirius Cursor before a battle against the Samnite legio linteata.

Moreover, January sees also the presence of Veiovis who appears as an anti-Jupiter, of Carmenta who is the goddess of birth and like Janus has two opposed faces, Prorsa and Postvorta (also named Antevorta and Porrima), of Iuturna, who as a gushing spring evokes the process of coming into being from non-being as the god of passage and change does.

According to Augustine,[164] Varro drew on the pontiff Mucius Scaevola's tripartite theology: Georg Wissowa stressed Jupiter's uniqueness as the only case among Indo-European religions in which the original god preserved his name, his identity and his prerogatives.

Wissowa considered Jupiter also a god of war and agriculture, in addition to his political role as guarantor of good faith (public and private) as Iuppiter Lapis and Dius Fidius, respectively.

The art of augury was considered prestigious by ancient Romans; by sending his signs, Jupiter (the sovereign of heaven) communicates his advice to his terrestrial colleague: the king (rex) or his successor magistrates.

As a further proof, Dumézil cites the story of Tullus Hostilius (the most belligerent of the Roman kings), who was killed by Jupiter with a lightning bolt (indicating that he did not enjoy the god's favour).

[184] Praeneste offers a glimpse into original Latin mythology: the local goddess Fortuna is represented as milking two infants, one male and one female, namely Jove (Jupiter) and Juno.

[188] Dumézil has elaborated an interpretative theory according to which this aporia would be an intrinsic, fundamental feature of Indoeuropean deities of the primordial and sovereign level, as it finds a parallel in Vedic religion.

[189] The contradiction would put Fortuna both at the origin of time and into its ensuing diachronic process: it is the comparison offered by Vedic deity Aditi, the Not-Bound or Enemy of Bondage, that shows that there is no question of choosing one of the two apparent options: as the mother of the Aditya she has the same type of relationship with one of his sons, Dakṣa, the minor sovereign.

Wissowa argued that while Jupiter is the god of the Fides Publica Populi Romani as Iuppiter Lapis (by whom important oaths are sworn), Dius Fidius is a deity established for everyday use and was charged with the protection of good faith in private affairs.

[213] This is in accord with the definition of the Penates of man being Fortuna, Ceres, Pales and Genius Iovialis and the statement in Macrobius that the Larentalia were dedicated to Jupiter as the god whence the souls of men come from and to whom they return after death.

[215] Dumézil sees the opposition Dius Fidius versus Summanus as complementary, interpreting it as typical to the inherent ambiguity of the sovereign god exemplified by that of Mitra and Varuna in Vedic religion.

In other words, Veiove is indeed the Capitoline god himself, who takes up a different, diminished appearance (iuvenis and parvus, young and gracile), in order to be able to discharge sovereign functions over places, times and spheres that by their own nature are excluded from the direct control of Jupiter as Optimus Maximus.

[258] The ambivalence in the identity of Veiove is apparent in the fact that while he is present in places and times which may have a negative connotation (such as the asylum of Romulus in between the two groves on the Capitol, the Tiberine island along with Faunus and Aesculapius, the kalends of January, the nones of March, and 21 May, a statue of his nonetheless stands in the arx.

[266] A. Pasqualini has argued that Veiovis seems related to Iuppiter Latiaris, as the original figure of this Jupiter would have been superseded on the Alban Mount, whereas it preserved its gruesome character in the ceremony held on the sanctuary of the Latiar Hill, the southernmost hilltop of the Quirinal in Rome, which involved a human sacrifice.

[284] In Dumézil's analysis, the function of Iuventas (the personification of youth), was to control the entrance of young men into society and protect them until they reach the age of iuvenes or iuniores (i.e. of serving the state as soldiers).

[290] According to Varro the Penates reside in the recesses of Heaven and are called Consentes and Complices by the Etruscans because they rise and set together, are twelve in number and their names are unknown, six male and six females and are the cousellors and masters of Jupiter.