Keynesian economics

In regards to employment, the condition referred to by Keynes as the "first postulate of classical economics" stated that the wage is equal to the marginal product, which is a direct application of the marginalist principles developed during the nineteenth century (see The General Theory).

A number of the policies Keynes advocated to address the Great Depression (notably government deficit spending at times of low private investment or consumption), and many of the theoretical ideas he proposed (effective demand, the multiplier, the paradox of thrift), had been advanced by authors in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Numerous concepts were developed earlier and independently of Keynes by the Stockholm school during the 1930s; these accomplishments were described in a 1937 article, published in response to the 1936 General Theory, sharing the Swedish discoveries.

[13] In 1930, he published A Treatise on Money, intended as a comprehensive treatment of its subject "which would confirm his stature as a serious academic scholar, rather than just as the author of stinging polemics",[14] and marks a large step in the direction of his later views.

[19] Keynes's younger colleagues of the Cambridge Circus and Ralph Hawtrey believed that his arguments implicitly assumed full employment, and this influenced the direction of his subsequent work.

The Liberal Party fought the 1929 General Election on a promise to "reduce levels of unemployment to normal within one year by utilising the stagnant labour force in vast schemes of national development".

[24] David Lloyd George launched his campaign in March with a policy document, We can cure unemployment, which tentatively claimed that, "Public works would lead to a second round of spending as the workers spent their wages.

"[25] Two months later Keynes, then nearing completion of his Treatise on money,[26] and Hubert Henderson collaborated on a political pamphlet seeking to "provide academically respectable economic arguments" for Lloyd George's policies.

[28] This became the mechanism of the "ratio" published by Richard Kahn in his 1931 paper "The relation of home investment to unemployment",[29] described by Alvin Hansen as "one of the great landmarks of economic analysis".

On page 174, Kahn rejects the claim that the effect of public works is at the expense of expenditure elsewhere, admitting that this might arise if the revenue is raised by taxation, but says that other available means have no such consequences.

"[44] Later the same year, speaking in a newly created Committee of Economists, Keynes tried to use Kahn's emerging multiplier theory to argue for public works, "but Pigou's and Henderson's objections ensured that there was no sign of this in the final product".

Later in the same chapter he tells us that: Ancient Egypt was doubly fortunate, and doubtless owed to this its fabled wealth, in that it possessed two activities, namely, pyramid-building as well as the search for the precious metals, the fruits of which, since they could not serve the needs of man by being consumed, did not stale with abundance.

Two pyramids, two masses for the dead, are twice as good as one; but not so two railways from London to York.But again, he does not get back to his implied recommendation to engage in public works, even if not fully justified from their direct benefits, when he constructs the theory.

On the contrary he later advises us that ... ... our final task might be to select those variables which can be deliberately controlled or managed by central authority in the kind of system in which we actually live ...[61]and this appears to look forward to a future publication rather than to a subsequent chapter of the General Theory.

Keynes takes note of this view in Chapter 2, where he finds it present in the early writings of Alfred Marshall but adds that "the doctrine is never stated to-day in this crude form".

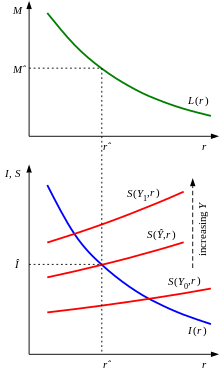

But under his Chapter 15 model a change in the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital has an effect shared between the interest rate and income in proportions depending on the partial derivatives of the liquidity preference function.

The term "liquidity trap" was coined by Dennis Robertson in his comments on the General Theory,[73] but it was John Hicks in "Mr. Keynes and the Classics"[74] who recognised the significance of a slightly different concept.

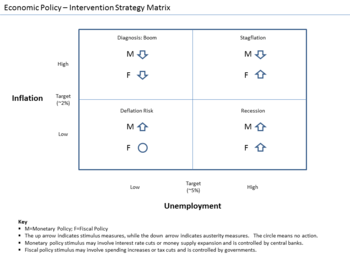

[78] An example of a counter-cyclical policy is raising taxes to cool the economy and to prevent inflation when there is abundant demand-side growth, and engaging in deficit spending on labour-intensive infrastructure projects to stimulate employment and stabilize wages during economic downturns.

The two governing principles of the plan were that the problem of settling outstanding balances should be solved by 'creating' additional 'international money', and that debtor and creditor should be treated almost alike as disturbers of equilibrium.

In the words of Geoffrey Crowther, then editor of The Economist, "If the economic relationships between nations are not, by one means or another, brought fairly close to balance, then there is no set of financial arrangements that can rescue the world from the impoverishing results of chaos.

From the crisis of 1929 onwards, noting the commitment of the British authorities to defend the gold parity of the pound sterling and the rigidity of nominal wages, he gradually adhered to protectionist measures.

[92] On 5 November 1929, when heard by the Macmillan Committee to bring the British economy out of the crisis, Keynes indicated that the introduction of tariffs on imports would help to rebalance the trade balance.

[92] In 1932, in an article entitled The Pro- and Anti-Tariffs, published in The Listener, he envisaged the protection of farmers and certain sectors such as the automobile and iron and steel industries, considering them indispensable to Britain.

While participating in the MacMillan Committee, he admitted that he no longer "believed in a very high degree of national specialisation" and refused to "abandon any industry which is unable, for the moment, to survive".

[92][93] In the Daily Mail of 13 March 1931, he called the assumption of perfect sectoral labour mobility "nonsense" since it states that a person made unemployed contributes to a reduction in the wage rate until he finds a job.

[94] He notes in National Self-Sufficiency:[94][92] A considerable degree of international specialization is necessary in a rational world in all cases where it is dictated by wide differences of climate, natural resources, native aptitudes, level of culture and density of population.

[96] Through the 1950s, moderate degrees of government demand leading industrial development, and use of fiscal and monetary counter-cyclical policies continued, and reached a peak in the "go go" 1960s, where it seemed to many Keynesians that prosperity was now permanent.

[110][111] The financial crisis of 2007–08, however, has convinced many economists and governments of the need for fiscal interventions and highlighted the difficulty in stimulating economies through monetary policy alone during a liquidity trap.

In the article Kalecki predicted that the full employment delivered by Keynesian policy would eventually lead to a more assertive working class and weakening of the social position of business leaders, causing the elite to use their political power to force the displacement of the Keynesian policy even though profits would be higher than under a laissez faire system: The elites would not care about risking the higher profits in the pursuit of reclaiming prestige in the society and the political power.

Keynes was largely supported by business leaders, bankers and conservative parties, or tripartite third way Catholics eager to avoid socialism after the Second World War.