Lancashire, Derbyshire and East Coast Railway

The Nottinghamshire coalfield continued to develop throughout the first half of the twentieth century, and several new connections to the former LD&ECR line were made.

There were plans to exploit the mineral deposits, but local transport links were unsatisfactory at the time, and Arkwright realised that he needed better railway connections to his property.

In fact several minor railways had been authorised in the past: in most cases their powers had long since lapsed, but the routes had been surveyed and were therefore presumably practicable.

[1][2] Elliott-Cooper and Emerson Muschamp Bainbridge, an eminent Engineer and the largest lessee of the North Derbyshire coalfield collaborated in the task of formulating a practicable scheme for the line.

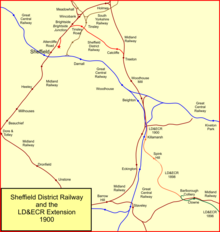

In the circumstances, the GER became the dominant force in the company, and it insisted on the first construction being limited to the main line between Chesterfield and Lincoln, with a branch to Beighton, which it was hoped would give access to Sheffield by running powers over the MS&LR.

The LD&ECR authorised lines west of Chesterfield were abandoned by the Lancashire, Derbyshire and East Coast Railway Act 1895 (58 & 59 Vict.

A junction with the Midland Railway at Clowne, and branches to Creswell, Langwith and Warsop Main collieries, as well as the north curve to the Great Northern at Tuxford were brought into use on the same date.

After several extensions of time granted by Parliament it was formally abandoned under the Lancashire, Derbyshire and East Coast Railway Act 1900 (63 & 64 Vict.

[16] In 1901 the Great Northern Railway completed its Leen Valley Extension line from Annesley, making a connection into the LD&ECR at Langwith Junction.

On 1 September 1902 the LD&ECR began running over the Leen Valley extension to and from Pleasley, Teversall, Silverhill and Kirkby collieries.

Until 1914 the spur and the LD&ECR line were used by boat trains from St Pancras to Heysham for the Isle of Man ferries on Saturdays.

[16] The LD&ECR had always wanted to reach Sheffield, but running powers over the MS&LR from Beighton were consistently refused.

[20] In 1897 construction of the LD&ECR Beighton branch north-westwards from Barlborough colliery junction was in progress; the Spink Hill tunnel of 501 yards was the chief engineering feature.

Its extension to the connection with the Midland Railway at Killamarsh (Beighton Junction), a further 1+1⁄2 miles, was opened on 29 May 1900 for goods traffic, and the following day for passengers.

[note 2][20] The Great Eastern Railway got access to Sheffield through its running powers agreement with the LD&ECR, a considerable benefit to that company, cheaply obtained.

[note 3][23] Six trains were operated each way daily between Langwith Junction and Sheffield with LD&ECR engines and rolling stock.

The last train of the day arrived at Sheffield Midland at 8.27 p.m. (Saturdays excepted), and was worked back empty to Attercliffe yard and attached to the LD&ECR goods train which left for Langwith Junction at 9.30 p.m.[17] In the autumn of 1896 the company was able to discard earlier plans to build a branch from Edwinstowe to Mansfield, when the Midland Railway agreed to give the LD&ECR and the Great Eastern Railway running powers for goods and coal traffic from Shirebrook to Mansfield.

[24] The passenger business in the eastern part of the system was disappointing, and early in 1902, the service between Langwith Junction and Lincoln was reduced from three to two trains each way, Mondays to Fridays.

The reversal of the Mansfield trains at Warsop was inconvenient, and on 1 October 1904 the Midland Railway commissioned a west curve to the LD&ECR at Shirebrook / Langwith Junction.

The Great Eastern Railway had the access it needed by virtue of its running powers, so it had no motivation to purchase the LD&ECR.

The LD&ECR route had originally been planned as a mineral railway, and in the twentieth century it struggled to sustain a passenger service.

[note 4] The trains between Chesterfield and Shirebrook North (later Langwith Junction) stopped from 3 December 1951, due to structural problems in Bolsover Tunnel.

[32] Goods trains continued to run to Chesterfield using the Duckmanton connections until March 1957, when the service was cut back to Arkwright Town.

[34] The last passenger usage of the line was a subsidised annual day trip organised by the Ollerton and Bevercotes Miners Welfare for the benefit of the local community.

Goods ceased over the remaining route east of High Marnham in 1980 after an accident at Clifton-on-Trent damaged the track beyond economic repair.

[40] The only substantial part of the line still in use is (2019) at the Tuxford Rail Innovation & Development Centre, formerly known as the High Marnham Test Track, and the connection to it from junctions at Shirebrook.

The projected route was to start from an inland port on the Manchester Ship Canal at Latchford, near Warrington, with also a short spur to the River Mersey; it was to proceed south eastward, and pass to the south of Knutsford where a short spur would make a branch with the Cheshire Lines Railway, giving access from Chester.

[citation needed] This was still proceeding when passenger train services began and, until it was finished, traffic had to be worked single line between Bolsover and Scarcliffe.

[55] In 1898, by the granting of running powers over the Great Northern Railway from Langwith to Kirkby Summit, access to four more collieries was obtained.

[2] Several more were connected later by new branch lines, in many cases after acquisition by the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway, and subsequent organisational ownership changes: sidings.