Language

[1] Human languages possess the properties of productivity and displacement, which enable the creation of an infinite number of sentences, and the ability to refer to objects, events, and ideas that are not immediately present in the discourse.

Language is thought to have gradually diverged from earlier primate communication systems when early hominins acquired the ability to form a theory of mind and shared intentionality.

[3][4] This development is sometimes thought to have coincided with an increase in brain volume, and many linguists see the structures of language as having evolved to serve specific communicative and social functions.

Humans acquire language through social interaction in early childhood, and children generally speak fluently by approximately three years old.

This definition stresses that human languages can be described as closed structural systems consisting of rules that relate particular signs to particular meanings.

[21][22] In the philosophy of language, the view of linguistic meaning as residing in the logical relations between propositions and reality was developed by philosophers such as Alfred Tarski, Bertrand Russell, and other formal logicians.

[28] However, one study has demonstrated that an Australian bird, the chestnut-crowned babbler, is capable of using the same acoustic elements in different arrangements to create two functionally distinct vocalizations.

[29] Additionally, pied babblers have demonstrated the ability to generate two functionally distinct vocalisations composed of the same sound type, which can only be distinguished by the number of repeated elements.

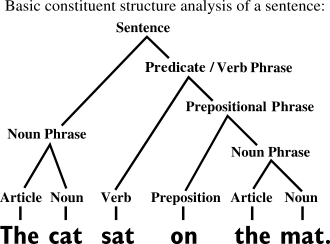

[32] Human languages differ from animal communication systems in that they employ grammatical and semantic categories, such as noun and verb, present and past, which may be used to express exceedingly complex meanings.

[35] Some theories are based on the idea that language is so complex that one cannot imagine it simply appearing from nothing in its final form, but that it must have evolved from earlier pre-linguistic systems among our pre-human ancestors.

The opposite viewpoint is that language is such a unique human trait that it cannot be compared to anything found among non-humans and that it must therefore have appeared suddenly in the transition from pre-hominids to early man.

Early human fossils can be inspected for traces of physical adaptation to language use or pre-linguistic forms of symbolic behaviour.

Among the signs in human fossils that may suggest linguistic abilities are: the size of the brain relative to body mass, the presence of a larynx capable of advanced sound production and the nature of tools and other manufactured artifacts.

"[46] Though cautioning against taking this story literally, Chomsky insists that "it may be closer to reality than many other fairy tales that are told about evolutionary processes, including language.

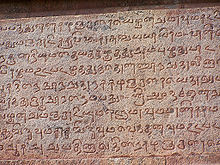

[49] The formal study of language is often considered to have started in India with Pāṇini, the 5th century BC grammarian who formulated 3,959 rules of Sanskrit morphology.

Early in the 20th century, Ferdinand de Saussure introduced the idea of language as a static system of interconnected units, defined through the oppositions between them.

People with a lesion in this area of the brain develop receptive aphasia, a condition in which there is a major impairment of language comprehension, while speech retains a natural-sounding rhythm and a relatively normal sentence structure.

[60][61] With technological advances in the late 20th century, neurolinguists have also incorporated non-invasive techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and electrophysiology to study language processing in individuals without impairments.

[58] Spoken language relies on human physical ability to produce sound, which is a longitudinal wave propagated through the air at a frequency capable of vibrating the ear drum.

Suprasegmental phenomena encompass such elements as stress, phonation type, voice timbre, and prosody or intonation, all of which may have effects across multiple segments.

[67] Human languages display considerable plasticity[1] in their deployment of two fundamental modes: oral (speech and mouthing) and manual (sign and gesture).

[87] Many other word classes exist in different languages, such as conjunctions like "and" that serve to join two sentences, articles that introduce a noun, interjections such as "wow!

[15] First language acquisition proceeds in a fairly regular sequence, though there is a wide degree of variation in the timing of particular stages among normally developing infants.

For example, in the Australian language Dyirbal, a married man must use a special set of words to refer to everyday items when speaking in the presence of his mother-in-law.

It makes it possible to store large amounts of information outside of the human body and retrieve it again, and it allows communication across physical distances and timespans that would otherwise be impossible.

Sound change is usually assumed to be regular, which means that it is expected to apply mechanically whenever its structural conditions are met, irrespective of any non-phonological factors.

A complex social process of "language making"[135] underlies these assignments of status and in some cases even linguistic experts may not agree (e.g. the One Standard German Axiom).

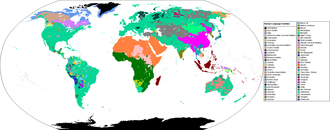

Linguists recognize many hundreds of language families, although some of them can possibly be grouped into larger units as more evidence becomes available and in-depth studies are carried out.

The Austronesian languages are considered to have originated in Taiwan around 3000 BC and spread through the Oceanic region through island-hopping, based on an advanced nautical technology.

[139] The areas of the world in which there is the greatest linguistic diversity, such as the Americas, Papua New Guinea, West Africa, and South-Asia, contain hundreds of small language families.