Writing systems of Africa

This is not to say writing was not present there prior to modern times; Tifinagh has been used by the Tuareg people since antiquity, as has the Geʽez script and its derivatives in the Horn of Africa.

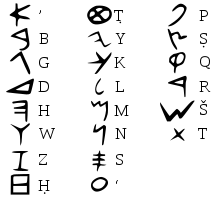

It was used from 300 BCE to 400 CE.The Tifinagh alphabet is still actively used to varying degrees in trade and modernized forms for writing of Berber languages (Tamazight, Tamashek, etc.)

[7] The symbols are at least several centuries old: early forms appeared on excavated pottery as well as what are most likely ceramic stools and headrests from the Calabar region, with a range of dates from 400 (and possibly earlier, 2000 BC[8]) to 1400 CE.

[13] Adinkra iconography has been adapted into several segmental scripts, including Lusona is a system of ideograms that functioned as mnemonic devices to record proverbs, fables, games, riddles and animals, and to transmit knowledge.

Neo-Tifinagh is an alphabet developed by Berber Academy to adopt Tuareg Tifinagh for use with Kabyle; it has been since modified for use across North Africa.

The adapted form of the script is also called Ajami, especially in the Sahel, and sometimes by specific names for individual languages, such as Wolofal, Sorabe, and Wadaad's writing.

Though the Latin Script was used to write Latin throughout Roman Africa and a handful of Latin-script inscriptions in the Punic language (more commonly written in the Phoenician script, as noted above) also survive,[45][46] the first systematic attempts to adapt it to African languages were probably those of Christian missionaries on the eve of European colonization (Pasch 2008).

One of the challenges in adapting the Latin script to many African languages was the use in those tongues of sounds unfamiliar to Europeans and thus without writing convention they could resort to.

Some resulting orthographies, such as the Yoruba writing system established by the late 19th century, have remained largely intact.

In the case of Hausa in Northern Nigeria, for instance, the colonial government was directly involved in determining the written forms for the language.

Since the colonial period, there have been efforts to propose and promulgate standardized or at least harmonized approaches to using the Latin script for African languages.

Braille, a tactile script widely used by the visually impaired, has been adapted to write several African languages- including those of Nigeria, South Africa and Zambia.

Around 1930, the English typewriter was modified by Ayana Birru of Ethiopia to type an incomplete and ligated version of the Amharic alphabet.

[49] The 1982 proposal for a unicase version of the African Reference Alphabet made by Michael Mann and David Dalby included a suggested typewriter adaptation.

[50] With early desktop computers it was possible to modify existing 8-bit Latin fonts to accommodate specialized character needs.

The earliest computer output of the Fidel was developed for a nine-pin dot matrix printer in 1983, by a team that included people from the Bible Society of Ethiopia, churches, and missions.

Unicode in principle resolves the issue of incompatible encoding, but other questions such as the handling of diacritics in extended Latin scripts are still being raised.

A number of contemporary and historic African scripts including Adlam, Bamum, Bassa Vah, Coptic, Egyptian Hieroglyphs, Garay, Ge'ez, Medefaidrin, Mende Ki-ka-ku, Meroitic, N'Ko, Osmanya, Tifinagh, and Vai are currently included in the Unicode standard, as are individual characters to other ranges of languages used, such as Latin and Arabic.