Languages of Taiwan

In the last 400 years, several waves of Han emigrations brought several different Sinitic languages into Taiwan.

Taiwan's long colonial and immigration history brought in several languages such as Dutch, Spanish, Hokkien, Hakka, Japanese, and Mandarin.

The situation had slightly changed since the 2000s when the government made efforts to protect and revitalize local languages.

It is common for young and middle-aged Hakka and aboriginal people to speak Mandarin and Hokkien better than, or to the exclusion of, their ethnic languages.

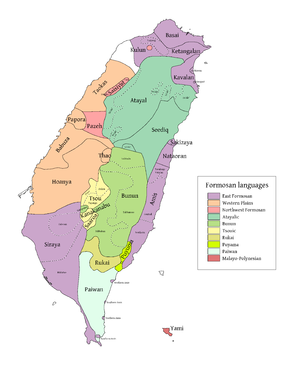

The governmental agency Council of Indigenous Peoples maintains the orthography of the writing systems of Formosan languages.

In recent decades the government started an aboriginal reappreciation program that included the reintroduction of Formosan mother tongue education in Taiwanese schools.

Some other language revitalization movements are going on Basay to the north, Babuza-Taokas in the most populated western plains, and Pazeh bordering it in the center west of the island.

Mandarin is commonly known and officially referred to as the national language (國語; Guóyǔ) in Taiwan.

In 1945, following the end of World War II, Mandarin was introduced as the de facto official language and made compulsory in schools.

Since then, Mandarin has been established as a lingua franca among the various groups in Taiwan: the majority Taiwanese-speaking Hoklo (Hokkien), the Hakka who have their own spoken language, the aboriginals who speak aboriginal languages; as well as Mainland Chinese immigrated in 1949 whose native tongue may be any Chinese variant.

Many Taiwanese, particularly the younger generations, speak Mandarin better than Hakka or Hokkien, and it has become a lingua franca for the island amongst the Chinese dialects.

Literary Taiwanese, which was originally developed in the 10th century in Fujian and based on Middle Chinese, was used at one time for formal writing but is now largely extinct.

Recent work by scholars such as Ekki Lu, Sakai Toru, and Lí Khîn-hoāⁿ (also known as Tavokan Khîn-hoāⁿ or Chin-An Li), based on former research by scholars such as Ông Io̍k-tek, has gone so far as to associate part of the basic vocabulary of the colloquial language with the Austronesian and Tai language families; however, such claims are not without controversy.

There are a reported 87,719 Hongkongers residing in Taiwan as of the early 2010s;[26] however, it is likely that this number has increased following emigration following political tension from the Anti-Extradition Ordinance Amendment Bill Movement protests in 2019 and 2020, and the Hong Kong national security law in 2020.

[27] Traditional Chinese characters are widely used in Taiwan to write Sinitic languages including Mandarin, Taiwanese Hokkien, Hakka and Cantonese.

Today, pure Classical Chinese is occasionally used in formal or ceremonial occasions and religious or cultural rites in Taiwan.

Buddhist texts, or sutras, are still preserved in Classical Chinese from the time they were composed or translated from Sanskrit sources.

[30] For example, most official notices and formal letters are written with a number of stock Classical Chinese expressions (e.g. salutation, closing).

Personal letters, on the other hand, are mostly written in the vernacular, but with some Classical phrases, depending on the subject matter, the writer's level of education, etc.

With the early influences of European missionaries, writing systems such as Sinckan Manuscripts, Pe̍h-ōe-jī, and Pha̍k-fa-sṳ were based on in Latin alphabet.

Currently, the official writing systems of Formosan languages are solely based on Latin and maintained by the Council of Indigenous Peoples.

The textbooks of Taiwanese Hokkien and Hakka are written in a mixed script of traditional Chinese characters and the Latin alphabet.

However, in August 2008, the central government announced that Hanyu Pinyin would be the only system of romanization of Standard Mandarin in Taiwan as of January 2009.

Bopomofo symbols are also mapped to the ordinary Roman character keyboard (1 = bo, q = po, a = mo, and so forth) used in one method for inputting Chinese text when using a computer.

The sole purpose of Zhuyin in elementary education is to teach standard Mandarin pronunciation to children.

School children learn the symbols so that they can decode pronunciations given in a Chinese dictionary and also so that they can find how to write words for which they know only the sounds.

[32] Many famous Taiwanese figures, including former Taiwanese President, Lee Teng-hui, and the founder of Nissin and inventor of instant ramen, Momofuku Ando, were considered to be native Japanese speakers due to being born in Japanese Taiwan.