Lenz's law

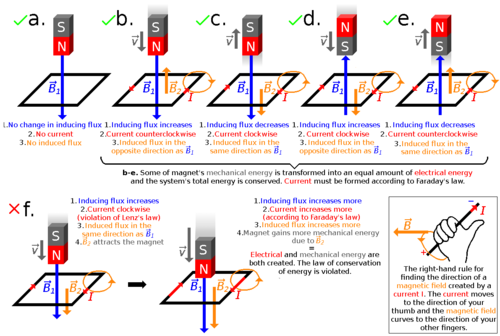

It is a qualitative law that specifies the direction of induced current, but states nothing about its magnitude.

Lenz's law predicts the direction of many effects in electromagnetism, such as the direction of voltage induced in an inductor or wire loop by a changing current, or the drag force of eddy currents exerted on moving objects in the magnetic field.

[4] Lenz's law states that: The current induced in a circuit due to a change in a magnetic field is directed to oppose the change in flux and to exert a mechanical force which opposes the motion.Lenz's law is contained in the rigorous treatment of Faraday's law of induction (the magnitude of EMF induced in a coil is proportional to the rate of change of the magnetic flux),[5] where it finds expression by the negative sign:

[6] This means that the direction of the back EMF of an induced field opposes the changing current that is its cause.

When a voltage is generated by a change in magnetic flux according to Faraday's law, the polarity of the induced voltage is such that it produces a current whose magnetic field opposes the change which produces it.

When net positive work is applied to a charge q1, it gains speed and momentum.

When q2 is inside a conductive medium such as a thick slab made of copper or aluminum, it more readily responds to the force applied to it by q1.

The energy of q1 is not instantly consumed as heat generated by the current of q2 but is also stored in two opposing magnetic fields.

However, the situation becomes more complicated when the finite speed of electromagnetic wave propagation is introduced (see retarded potential).

[9] Famous 19th century electrodynamicist James Clerk Maxwell called this the "electromagnetic momentum".