Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark

Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark (1796) is a personal travel narrative by the eighteenth-century British feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft.

While the book initially inspired readers to travel to Scandinavia, it failed to retain its popularity after the publication of Godwin's Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman in 1798, which revealed Wollstonecraft's unorthodox private life.

In 1790, at the age of thirty-one, Wollstonecraft made a dramatic entrance onto the public stage with A Vindication of the Rights of Men, a work that helped propel the British pamphlet war over the French Revolution.

[citation needed] One month after her attempted suicide, Wollstonecraft agreed to undertake the long and treacherous journey to Scandinavia in order to resolve Imlay's business difficulties.

[citation needed] Although Wollstonecraft appears as only a tourist in Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, during her travels she was actually conducting delicate business negotiations on behalf of Imlay.

For almost two hundred years, it was unclear why she had travelled to Scandinavia, but in the 1980s historian Per Nyström uncovered documents in local Swedish and Norwegian archives that shed light on the purpose of her trip.

On 18 June 1794, Peder Ellefsen, who belonged to a rich and influential Norwegian family, bought a ship called the Liberty from agents of Imlay in Le Havre, France.

Leaving Fanny and her nurse Marguerite behind, she embarked for Strömstad, Sweden, where she took a short detour to visit the fortress of Fredriksten, and then proceeded to Larvik, Norway.

Wollstonecraft's political commentary extends the ideas she had presented in An Historical and Moral View of the French Revolution (1794); her discussion of prison reform, for example, is informed by her own experiences in revolutionary France and those of her friends, many of whom were jailed.

[18] After overturning the conventions of political and historical writing, Wollstonecraft brought what scholar Gary Kelly calls "Revolutionary feminism" to yet another genre that had typically been considered the purview of male writers,[18] transforming the travel narrative's "blend of objective facts and individual impressions ... into a rationale for autobiographical revelation".

[19] As one editor of the Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark writes, the book is "nothing less than a revolution in literary genres"; its sublimity, expressed through scenes of intense feeling, made "a new wildness and richness of emotional rhetoric" desirable in travel literature.

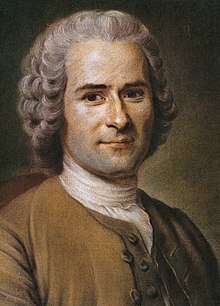

[22] Several of Rousseau's themes appear in the Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, such as "the search for the source of human happiness, the stoic rejection of material goods, the ecstatic embrace of nature, and the essential role of sentiment in understanding".

[24] Heavily influenced by Rousseau's frank and revealing Confessions (1782), Wollstonecraft lays bare her soul in Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, detailing not only her physical but also her psychological journey.

The impetuous dashing of the rebounding torrent from the dark cavities which mocked the exploring eye, produced an equal activity in my mind: my thoughts darted from earth to heaven, and I asked myself why I was chained to life and its misery?

Still the tumultuous emotions this sublime object excited, were pleasurable; and, viewing it, my soul rose, with renewed dignity, above its cares – grasping at immortality – it seemed as impossible to stop the current of my thoughts, as of the always varying, still the same, torrent before me – I stretched out my hand to eternity, bounding over the dark speck of life to come.

As one scholar puts it, "because Wollstonecraft is a woman, and is therefore bound by the legal and social restrictions placed on her sex in the eighteenth century, she can only envisage autonomy of any form after death".

Some scholars contend that Wollstonecraft uses the imagination to liberate the self, especially the feminine self; it allows her to envision roles for women outside the traditional bounds of eighteenth-century thought and offers her a way to articulate those new ideas.

I tried to correct this fault, if it be one, for they were designed for publication; but in proportion as I arranged my thoughts, my letter, I found, became stiff and affected: I, therefore, determined to let my remarks and reflections flow unrestrained, as I perceived that I could not give a just description of what I saw, but by relating the effect different objects had produced on my mind and feelings, whilst the impression was still fresh.

[39] However, Wollstonecraft still views civilization's tragedies as worthier of concern than individual or fictional tragedies, suggesting that, for her, sympathy is at the core of social relations:[40] I have then considered myself as a particle broken off from the grand mass of mankind; — I was alone, till some involuntary sympathetic emotion, like the attraction of adhesion, made me feel that I was still a part of a mighty whole, from which I could not sever myself—not, perhaps, for the reflection has been carried very far, by snapping the thread of an existence which loses its charms in proportion as the cruel experience of life stops or poisons the current of the heart.

As in previous works, she discusses concrete issues such as childcare and relationships with servants, but unlike her more polemical books such as Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1787) or the Rights of Woman, this text emphasizes her emotional reactions to nature and maternity.

With trembling hand I shall cultivate sensibility, and cherish delicacy of sentiment, lest, whilst I lend fresh blushes to the rose, I sharpen the thorns that will wound the breast I would fain guard – I dread to unfold her mind, lest it should render her unfit for the world she is to inhabit – Hapless woman!

While the Rights of Woman argued that women should be "useful" and "productive", importing the language of the market into the home, Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark adopts the values of the domestic space for the larger social and political world.

[51] Although Wollstonecraft spends much of Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark musing on nature and its connection to the self, a great deal of the text is actually about the debasing effects of commerce on culture.

Throughout Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, she attaches criticisms of commerce to the anonymous lover who has betrayed her: A man ceases to love humanity, and then individuals, as he advances in the chase after wealth; as one clashes with his interest, the other with his pleasures: to business, as it is termed, every thing must give way; nay, is sacrificed; and all the endearing charities of citizen, husband, father, brother, become empty names.

[56] Wollstonecraft spends several large sections of Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark speculating about the possibilities of social and political revolution and outlining a trajectory for the progress of civilization.

In comparing Norway with Britain and France, for example, she argues that the Norwegians are more progressive because they have a free press, embrace religious toleration, distribute their land fairly, and have a politically active populace.

[68] As Favret argues, almost all of the responses to Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark placed the narrator/Mary in the position of a sentimental heroine, while the text itself, with its fusion of sensibility and politics, actually does much to challenge that image.

[70] Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark was republished at the end of the nineteenth century and Robert Louis Stevenson, the author of Treasure Island, took a copy on his trip to Samoa in 1890.

"[73] The book's combination of progressive social views with the advocacy of individual subjective experience influenced writers such as William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

[75] Her book also had a significant influence on Coleridge's Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1797–99) and Percy Shelley's Alastor (1815); their depictions of "quest[s] for a settled home" strongly resemble Wollstonecraft's.