Joseph Johnson (publisher)

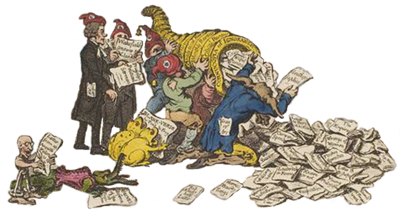

In the 1790s, Johnson aligned himself with the supporters of the French Revolution, and published an increasing number of political pamphlets in addition to a prominent journal, the Analytical Review, which offered British reformers a voice in the public sphere.

[5] At the age of fifteen, Johnson was apprenticed to George Keith, a London bookseller who specialized in publishing religious tracts such as Reflections on the Modern but Unchristian Practice of Innoculation.

As Gerald Tyson, Johnson's major modern biographer, explains, it was unusual for the younger son of a family living in relative obscurity to move to London and to become a bookseller.

Two of his early publications were a kind of day planner: The Complete Pocket-Book; Or, Gentleman and Tradesman's Daily Journal for the Year of Our Lord, 1763 and The Ladies New and Polite Pocket Memorandum Book.

Through Priestley's recommendation, Johnson was able to issue the works of many Dissenters, especially those from Warrington Academy: the poet, essayist, and children's author Anna Laetitia Barbauld; her brother, the physician and writer, John Aikin; the naturalist Johann Reinhold Forster; the Unitarian minister and controversialist Gilbert Wakefield; the moralist William Enfield; and the political economist Thomas Malthus.

"[14] By printing the works of Priestley and other of the Warrington tutors, Johnson also made himself known to an even larger network of Dissenting intellectuals, including those in the Lunar Society, which expanded his business further.

[21] The late 1760s was a time of growing radicalism in Britain, and although Johnson did not participate actively in the events, he facilitated the speech of those who did, e.g., by publishing works on the disputed election of John Wilkes and the American Revolution.

With some difficulty, as Unitarians were feared at that time and their beliefs held illegal until the Doctrine of the Trinity Act 1813, Johnson obtained the building for Essex Street Chapel and, with the help of barrister John Lee, who later became Attorney-General, its licence.

[33] For example, he published the Reverend George Gregory's 1787 English translation of Bishop Robert Lowth's seminal book on Hebrew poetry, De Sacra Poesi Hebraeorum.

[34] Yet, as Helen Braithwaite writes in her study of Johnson, his "enlightened pluralistic approach was also seen by its opponents as inherently permissive, opening the door to all forms of unhealthy questioning and scepticism, and at odds with the stable virtues of established religion and authority".

[36] Johnson continued his series of anti-government, pro-American pamphlets by publishing Fast Day sermons by Joshua Toulmin, George Walker, Ebenezer Radcliff, and Newcome Cappe.

[37] Braithwaite describes these as "well-articulated critiques of government" that "were not only unusual but potentially subversive and disruptive", and she concludes that Johnson's decision to publish so much of this material indicates that he supported the political position it espoused.

[2] Not only did Johnson encourage the writing of British children's literature, but he also helped sponsor the translation and publication of popular French works such as Arnaud Berquin's L'Ami des Enfans (1782–83).

[29][50] Although Johnson had begun his career as a relatively cautious publisher of religious and scientific tracts, he was now able to take more risks and he encouraged friends to recommend works to him, creating a network of informal reviewers.

Johnson issued Cowper's Poems (1782) and The Task (1784) at his own expense (a generous action at a time when authors were often forced to take on the risk of publication) and was rewarded with handsome sales of both volumes.

[58] He also published the work of James Earle, a prominent surgeon, whose significant book on lithotomy was illustrated by William Blake, and Matthew Baillie's Morbid Anatomy (1793), "the first text of pathology devoted to that science exclusively by systematic arrangement and design".

[66] Although there were few regulars, except perhaps for Johnson's close London friends (Fuseli, Bonnycastle and, later, Godwin), the large number of high-profile guests, including Thomas Paine, attests to the reputation of these dinners.

[2][72] As radicalism took hold in Britain in the 1790s, Johnson became increasingly involved in its causes: he was a member of the Society for Constitutional Information, which was attempting to reform Parliament; he published works defending Dissenters after the religiously motivated Birmingham Riots in 1791; and he testified on behalf of those arrested during the 1794 Treason Trials.

[29] Johnson published works championing the rights of slaves, Jews, women, prisoners, Dissenters, chimney sweeps, abused animals, university students forbidden from marrying, victims of press gangs, and those unjustly accused of violating the game laws.

Johnson's determination to publish political and revolutionary works, however, fractured his Circles: Dissenters were alienated from Anglicans during efforts to repeal the Test and Corporation Acts and moderates split from radicals during the French revolution.

Thomas Cooper, who had also written a response to Burke, was later informed by the Attorney General that "although there was no exception to be taken to his pamphlet when in the hands of the upper classes, yet the government would not allow it to appear at a price which would insure its circulation among the people".

[89] Johnson continued to publish the poetic works of Aikin and Barbauld as well as those of George Dyer, Joseph Fawcett, James Hurdis, Joel Barlow, Ann Batten Cristall and Edward Williams.

In particular, he promoted the translation of the works of persecuted French Girondins, such as Condorcet's Outlines of an Historical View of the Progress of the Human Mind (1795) and Madame Roland's An Appeal to Impartial Posterity (1795), which he had released in English within weeks of its debut in France.

Founded by his neighbour Richard Phillips and edited by his friend John Aikin, it was associated with Dissenting interests and was responsible for importing much German philosophical thought into England.

Despite having retained Thomas Erskine as his lawyer, who had successfully defended Hardy and Horne Tooke at the 1794 Treason Trials, and character references from George Fordyce, Aikin, and Hewlett, Johnson was fined £50 and sentenced to six months imprisonment at King's Bench Prison in February 1799.

Braithwaite speculates: If the conduct of the Attorney-General and the Anti-Jacobin are to serve as any kind of barometer of government opinion, then other scores were clearly being settled and it was not merely for [Johnson's] involvement in the sale of Wakefield's pamphlet but his tenure ... as a stubbornly independent-minded publisher in St Paul's Churchyard, prominently serving the irreligious and unconstitutional interests of 'rational' dissent and dangerously sympathetic to the ideas of foreigners (most visibly through the pages of the Analytical) that Joseph Johnson was ultimately being brought to book.

[29][110] Johnson's authors became increasingly frustrated with him towards the end of his life, Wakefield calling him "heedless, insipid, [and] inactive" and Lindsey describing him as "a worthy and most honest man, but incorrigably [sic] neglectful often to his own detriment".

[111] Priestley, by then in Pennsylvania, eventually broke off his forty-year relationship with the publisher, when his book orders were delayed several years and Johnson failed to communicate with him regarding the publication of his works.

[116] William Godwin's obituary of 21 December 1809 in the Morning Chronicle was particularly eloquent,[117] calling Johnson an "ornament to his profession" and praising his modesty, his warm heart, and the integrity and clarity of his mind.

His friend John Aikin explained that he had "a decided aversion to all sorts of puffing and parade";[126] Johnson's unassuming character has left historians and literary critics sparse material from which to reconstruct his life.

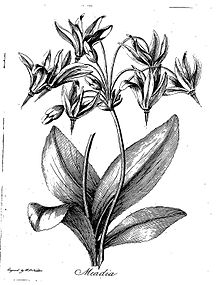

MEADIA's soft chains five suppliant beaux confess,

And hand in hand the laughing belle address;

Alike to all, she bows with wanton air,

Rolls her dark eye, and waves her golden hair. (I.61–64) [ 90 ]