Lewis Carroll

An avid puzzler, Carroll created the word ladder puzzle (which he then called "Doublets"), which he published in his weekly column for Vanity Fair magazine between 1879 and 1881.

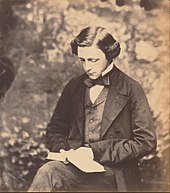

[27] The young adult Charles Dodgson was about 6 feet (1.83 m) tall and slender, and he had curly brown hair and blue or grey eyes (depending on the account).

Dodgson himself seems to have been far more acutely aware of it than most people whom he met; it is said that he caricatured himself as the Dodo in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, referring to his difficulty in pronouncing his last name, but this is one of the many supposed facts often repeated for which no first-hand evidence remains.

He lived in a time when people commonly devised their own amusements and when singing and recitation were required social skills, and the young Dodgson was well equipped to be an engaging entertainer.

[30] William Tuckwell, in his Reminiscences of Oxford (1900), regarded him as "austere, shy, precise, absorbed in mathematical reverie, watchfully tenacious of his dignity, stiffly conservative in political, theological, social theory, his life mapped out in squares like Alice's landscape".

In The Life and Letters of Lewis Carroll, the editor states that "his Diary is full of such modest depreciations of himself and his work, interspersed with earnest prayers (too sacred and private to be reproduced here) that God would forgive him the past, and help him to perform His holy will in the future.

[39] In 1856, Dean Henry Liddell arrived at Christ Church at Oxford University, bringing with him his young family, all of whom would figure largely in Dodgson's life over the following years, and would greatly influence his writing career.

It has been noted that Dodgson himself repeatedly denied in later life that his "little heroine" was based on any real child,[40][41] and he frequently dedicated his works to girls of his acquaintance, adding their names in acrostic poems at the beginning of the text.

[41] Information is scarce (Dodgson's diaries for the years 1858–1862 are missing), but it seems clear that his friendship with the Liddell family was an important part of his life in the late 1850s, and he grew into the habit of taking the children on rowing trips (first the boy, Harry, and later the three girls) accompanied by an adult friend[42] to nearby Nuneham Courtenay or Godstow.

Indeed, according to one popular story, Queen Victoria herself enjoyed Alice in Wonderland so much that she commanded that he dedicate his next book to her, and was accordingly presented with his next work, a scholarly mathematical volume entitled An Elementary Treatise on Determinants.

[62] Dodgson also made many studies of men, women, boys, and landscapes; his subjects also include skeletons, dolls, dogs, statues, paintings, and trees.

[64] During the most productive part of his career, he made portraits of notable sitters such as John Everett Millais, Ellen Terry, Maggie Spearman, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Julia Margaret Cameron, Michael Faraday, Lord Salisbury, and Alfred Tennyson.

[69][70] Another invention was a writing tablet called the nyctograph that allowed note-taking in the dark, thus eliminating the need to get out of bed and strike a light when one woke with an idea.

[82] Robbins' and Rumsey's investigation[83] of Dodgson condensation, a method of evaluating determinants, led them to the alternating sign matrix conjecture, now a theorem.

[86] The two volumes of his last novel, Sylvie and Bruno, were published in 1889 and 1893, but the intricacy of this work was apparently not appreciated by contemporary readers; it achieved nothing like the success of the Alice books, with disappointing reviews and sales of only 13,000 copies.

[90] Dodgson died of pneumonia following influenza on 14 January 1898 at his sisters' home, "The Chestnuts", in Guildford in the county of Surrey, just four days before the death of Henry Liddell.

It explored the possibility that Dodgson's rift with the Liddell family (and his temporary suspension from the college) might have been caused by improper relations with their children, including Alice.

The research for the documentary found a "disturbing" full frontal nude of Alice's adolescent sister Lorina during filming,[94] and speculated on the "likelihood" of Dodgson taking the photo.

[101] Edward Wakeling's paper/review "Eight or nine wise words on documentary making" [1] appeared in March 2015 as part of the Lewis Carroll society newsletter Bandersnatch.

[105] Cohen goes on to note that Dodgson "apparently convinced many of his friends that his attachment to the nude female child form was free of any eroticism", but adds that "later generations look beneath the surface" (p. 229).

[110] He claims that Dodgson's diaries contained numerous entries that reveal an appreciation for adult women, as well as their appearance in art and theatre, even "vulgar" entertainment.

Lebailly claims that studies of child nudes were mainstream and fashionable in Dodgson's time and that most photographers made them as a matter of course, including Oscar Gustave Rejlander and Julia Margaret Cameron.

Lebailly concludes that it has been an error of Dodgson's biographers to view his child-photography with 20th- or 21st-century eyes, and to have presented it as some form of personal idiosyncrasy, when it was a response to a prevalent aesthetic and philosophical movement of the time.

She argues that the allegations of paedophilia rose initially from a misunderstanding of Victorian morals, as well as the mistaken idea – fostered by Dodgson's various biographers – that he had no interest in adult women.

She drew attention to the large amounts of evidence in his diaries and letters that he was also keenly interested in adult women, married and single, and enjoyed several relationships with them that would have been considered scandalous by the social standards of his time.

[112] She argues that suggestions of paedophilia emerged only many years after his death, when his well-meaning family had suppressed all evidence of his relationships with women in an effort to preserve his reputation, thus giving a false impression of a man interested only in little girls.

Similarly, Leach points to a 1932 biography by Langford Reed as the source of the dubious claim that many of Carroll's female friendships ended when the girls reached the age of 14.

Until a primary source is discovered, the events of 27 June 1863 will remain in doubt; however, a 1930 letter from the younger Lorina Liddell to Alice may shed light on the matter.

[129] Some authors, Sadi Ranson in particular, have suggested that Carroll had temporal lobe epilepsy in which consciousness is not always completely lost but altered, and in which the symptoms mimic many of the same experiences as Alice in Wonderland.

Carroll had at least one incident in which he suffered full loss of consciousness and awoke with a bloody nose, which he recorded in his diary and noted that the episode left him not feeling himself for "quite sometime afterward".