Literature of al-Andalus

The 20th century Moroccan scholar of literature Abdellah Guennoun cites the Friday sermon of the Amazigh general Tariq ibn Ziyad to his soldiers upon landing in Iberia as a first example.

[5] The content of the conquerors' poetry was often boasting about noble heritage, celebrating courage in war, expressing nostalgia for homeland, or elegy for those lost in battle, though all that remains from this period is mentions and descriptions.

[7] The bustling economy of al-Andalus allowed al-Hakam I to invest in education and literacy; he built 27 madrasas in Cordoba and sent missions to the east to procure books to be brought back to his library.

[7] al-Fakhoury cites Reinhart Dozy in his 1881 Histoire des Musulmans d'Espagne: "Almost all of Muslim Spain could read and write, while the upper class of Christian Europe could not, with the exception of the clergy.

[5] Religious study grew and spread, and the Iberian Umayyads, for political reasons, adopted the Maliki school of jurisprudence, named after the Imam Malik ibn Anas and promoted by Abd al-Rahman al-Awza'i.

It was also heralded by Ibn Hazm, a polymath at the forefront of all kinds of literary production in the 11th century, widely acknowledged as the father of comparative religious studies,[8] and who wrote Al-Fisal fi al-Milal wa al-Nihal [ar] (The Separator Concerning Religions, Heresies, and Sects).

[5] The most important of these was told the history of al-Andalus from the Islamic conquest to the time of the author, as seen in the work of the Umayyad court historian and genealogist Ahmed ar-Razi (955) News of the Kings of al-Andalus (أخبار ملوك الأندلس وخدمتهم وغزواتهم ونكباتهم) and that of his son Isa, who continued his father's work and whom Ibn al-Qūṭiyya cited.

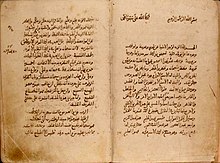

[18] The collection Al-ʿIqd al-Farīd by Ibn Abd Rabbih (940) could be considered the first Andalusi literary work, though its contents relate to the Mashriq.

[7] The muwashshah has gained importance recently among Orientalists because of its possible connection to early Spanish and European folk poetry and the troubadour tradition.

[22] Court poetry followed tradition until the 11th century, when it took a bold new form: the Umayyad caliphs sponsored literature and worked to gather texts, as evidenced in the library of al-Hakam II.

[5] However, urban Andalusi poetry started with Ibn Darraj al-Qastalli (1030), under Caliph al-Mansur, who burned the library of al-Hakam fearing that science and philosophy were a threat to religion.

[5] Ibn Shahid [ar] led a movement of poets of the aristocracy opposed to the folksy muwashshah and fanatical about eloquent poetry and orthodox Classical Arabic.

[26] Qasmuna Bint Ismā'īl was mentioned in Ahmed Mohammed al-Maqqari's Nafah at-Tīb [ar] as well as al-Suyuti's 15th century anthology of female poets.

[3] He wrote Dialogi contra Iudaeos, an imaginary conversation between a Christian and a Jew, and Disciplina Clericalis, a collection of Eastern sayings and fables in a frame-tale format present in Arabic literature such as Kalīla wa-Dimna.

[29][30] Joseph ben Judah ibn Aknin (c. 1150 – c. 1220) was polymath and prolific writer born in Barcelona and moved to North Africa under the Almohads, settling in Fes.

[33][35] Among the Latin works of early Mozarabic culture, historiography is especially important, since it constitutes the earliest record from al-Andalus of the conquest period.

The political unification of Morocco and al-Andalus under the Almoravid dynasty rapidly accelerated the cultural interchange between the two continents, beginning when Yusuf Bin Tashfiin sent al-Mu'tamid ibn Abbad into exile in Tangier and ultimately Aghmat.

[43][44] In the Almoravid period two writers stand out: the religious scholar and judge Ayyad ben Moussa and the polymath Ibn Bajja (Avempace).

The abolishment of the dhimmi status further stifled the once flourishing Jewish Andalusi cultural scene; Maimonides went east and many Jews moved to Castillian-controlled Toledo.

[53] With the continents united under empire, the development and institutionalization of Sufism was a bi-continental phenomenon taking place on both sides of the Strait of Gibraltar.

[5] Ibn Sab'in was a Sufi scholar from Ricote who wrote the Sicilian Questions in response to the inquiries of Frederick II of Sicily.

[5] Ṣafwān ibn Idrīs (d. 1202) of Murcia wrote a biographical dictionary of recent poets, Zād al-musāfir wa-ghurrat muḥayyā ʾl-adab al-sāfir.

[60] The prophetic biography Kitab al-anwar (or Libro de las luces) of Abu al-Hasan Bakri—or else the work on which his final redaction was based—was in circulation in al-Andalus in the 12th century, when a translation into Latin was made for the Corpus Cluniacense.

[5] Ibn Sahib al-Salat wrote al-Mann bi ʾl-imāma ʿala ʾmustaḍʿafīn bi-an jaʿalahum Allāh al-aʿimma wa-jaʿalahum al-wārithīn, although only the second volume survives, covering the years 1159–1172.

[62] Muhammad al-Idrisi stood out in geography and in travel writing: Abu Hamed al-Gharnati [ar], Ibn Jubayr, and Mohammed al-Abdari al-Hihi.

[5] Abu Ishaq Ibrahim al-Kanemi, an Afro-Arab poet from Kanem, was active in Seville writing panegyric qasidas for Caliph Yaqub al-Mansur.

[5] Abu al-Qasim ash-Shāṭibī of Játiva went to Cairo and authored Ḥirz al-amānī fī wajh al-tahānī or al-Qaṣīda al-shāṭibiyya [ar], a didactic book in verse teaching Abu'Amr ad-Dani's [es] al-Taysīr fī l-qirāʼāt al-sabʽ [ar] on Quranic readings[18] of the Imams Nafiʽ, Ibn Kathir, Abu Amr, Ibn Amir, Aasim, Hamzah, and Al-Kisa'i.

[3][69] The agriculturalist Ibn al-'Awwam, active in Seville in the late 12th century, wrote Kitab al-Filaha [ar], considered the most comprehensive medieval book in Arabic on agriculture.

[81] A famous example is la Verdadera historia del rey don Rodrigo by Miguel de Luna [es].

[82] Dwight Fletcher Reynolds describes a 'rhyme revolution' in al-Andalus that occurred in the late tenth or early eleventh century with the strophic muwaššah and zajal genres, which broke with the meter and mono-endrhyme of Arabic courtly song traditions.