Litvinism

[1] The Polish historian Feliks Koneczny used the terms letuwskije, Letuwa and letuwini to describe the "fake Lithuanians" in his book Polska między Wschodem i Zachodem, 'Poland between East and West', and other works.

[1] M. Yermalovich considers Samogitia as the country's sole Baltic territory, while Aukštaitija is an artificially conceived ethnographic region occupying a part of the Belarusian lands.

[1] Litvinism is mostly espoused in books published in Belarus and on the Internet, as well as in English, which target a foreign audience in an attempt to disseminate M. Yermalovich's "discoveries" and the "real" history of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

The Litvinists underline their closeness to Lithuanians, Poles and Ukrainians (Ruthenians) viewing the Grand Duchy of Lithuania as a common heritage of the nations that live on its former territory.

[46] Moreover, Syrokomla described his experience talking with a Lithuanian villager near Kernavė as follows: "tu kiedym się chciał wieśniaka o cóś rozpytać, niezrozumiał mię i zbył jedném słowem ne suprantu.

[54] Subsequently, according to Sahanovič, there was a major shift in the 1930s and 1940s when historians in the Byelorussian SSR presented Russia positively, while the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was then described as "predatory" and "alien" country for the Belarusian statehood.

[19] On 7 October 1939, a rally was held in the Lukiškės Square which demanded to attach the Vilnius Region to the Byelorussian SSR, whose numbers of attendees the Soviet propaganda had inflated to 75,000 people.

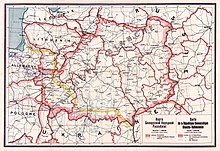

[9] Arłou claims that the Vilnius Region was historically and ethnically Belarusian since the early Middle Ages and that for centuries the Belarusians-Lićviny (Беларусы-ліцьвіны) composed the majority of its population.

[58] In 1972, Urban published a book In the light of historical facts (У сьвятле гістарычных фактаў) where he equated Lithuania ("Litva") and Litvins ("ліцьвіны [Lićviny]") to Western Baltic Slavs.

[62] However, in 1992 Piatro Kravchanka, the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Belarus, told the Reuters correspondent that the Vilnius Region should belong to Belarus (the ministry later apologized for these words), while Zianon Pazniak, the founder and leader of the Belarusian Popular Front, spoke about possible Belarusian claims to the territories of the Republic of Lithuania during his visit to the Supreme Council of the Republic of Lithuania in Vilnius.

"[68] On 20 May 2000, a group of mostly Belarusian Litvinists in Novogrudok signed the Act of Proclamation of the Litvin nation, while its members consider that in 1900-1922 the Old Lithuania died and the name "Lithuanians" was assigned to the Samogitians.

[75] On January 22, 2009, a public organizing committee Lithuania Millennium was formed to commemorate the first mentioning of the name of Lithuania in written sources in 1009 (its chairman was professor Anatol Hrytskievich and it also included: writer Voĺha Ipatava [be], historian Alexander Kravtsevich, professor Alieś Astroŭski [be], biologist Aliaksiej Mikulič [be], archeologist Edvard Zajkoŭski [be], painter Aliaksiej Maračkin [be], priest Lieanid Akalovič, writer Zdzislaŭ Sićka [be]).

[24] Also, according to Pazniak, due to struggle in the Belarusian–Russian relations during the national revival in the 19th century, the Samogitians (Belarusian: Жамойць), who according to him allegedly did not even have their own writing system, benefited by choosing the name "Літва [Litva]" and built a fantastic state ideology.

[17] According to Alvydas Nikžentaitis, the director of Lithuanian Institute of History, this theory is not new, but has been known for a long time and has its fans and followers in Belarus; however, even some Belarusian historians regard Alexander Kravtsevich as a radical and refuse to cooperate with him.

[86][87][88] Belsat TV show where historians gather and promote Litvinism is called Intermarium, which is named after Józef Piłsudski's post-World War I geopolitical plan of a future federal state in Central and Eastern Europe dominated by Poland.

[18] Furthermore, according to Sańko, Moscow made two "expensive gifts" to Lithuania when it "gave Vilnius from us [Belarus]" in 1939 and "organized" the 1995 Belarusian referendum to change the national state symbols.

[31] According to Viačorka and Šupa, every Belarusian should know that Lithuania is also his ancient country and "childish complexes" about it should be discarded, while the imposition of a word "Letuva" is "monstrous" and instead there is a necessity of historical education.

[14][96] According to Aleś Čajčyc, the Information Secretary of the Rada of the Belarusian Democratic Republic,[97] the Litvinism article on English Wikipedia was written by "Lithuanian marginals".

[98] However, the same year after secretary's statement the official Twitter account of the exiled government tweeted that the coat of arms is "a symbol of centuries of friendship between Belarusians and Lithuanians".

[115] On 27 October 2023, Čajčyc suggested to make Belarusian, Lithuanian ("летувіскую [letuviskuju]") and Polish as semi-official languages in the region compromising of Białystok, Vilnius, and Grodno.

[121][122] On 24 March 2024, Pazniak congratulated the Belarusians with Freedom Day and claimed that factually in 1918 the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was restored but with a name Belarus, while in the territory of Samogitia appeared "Letuva".

[178] Petras Auštrevičius, Member of the European Parliament, also named Litvinism as a hybrid warfare designed to antagonize nations, create mistrust and historical revanchism.

[187] According to Justinas Dementavičius, a scientist of the Vilnius University Institute of International Relations and Political Science, Litvinism is a romantic or radical form of Belarusian nationalism, which questions the fact that historically the Lithuanians created the State of Lithuania.

[188] One of the members of the Lithuanian coalition government, Liberals' Movement, announced that the purpose of the discussion in Seimas Palace was searching for ways to stop the radical Litvinism ideology.

[6] Moreover, Savukynas pointed out to the fact that in the early 20th century a monument was unveiled in Vilnius dedicated to the Russian Empress Catherine the Great with inscription "separated to recover".

[6] In an interview held by Lietuvos rytas, the Belarusian journalist Alesis Mikas stated that the Russian Government could be using the new phenomenon of Litvinism in Belarus as a form of hybrid warfare against Lithuania.

Lev Krishtapovich claims that:In fact, under the guise of Belarusian nationalism, or the so-called Litvinism, a Polish gentry clique stands aimed at transforming Belarus into Poland's eastern frontiers.

[194][195] According to another strategy, it is claimed that the GDL also supposedly was a Russian (Ruthenian) state ("more democratic"), which has nothing to do nor with the 20th century "Samogitian" statehood of Lithuania, nor with Ukraine and Belarus as historical entities.

[205] In 2011, Belarusian Exarchate of the Moscow Patriarchate initiated the canonization of the former Metropolitan of Vilnius Joseph Semashko who was the primary organizer of the Synod of Polotsk in 1839 during which the 1596 Union of Brest was abolished.

[206] Consequently, Lithuanian and Belarusian Uniates became part of the Russian Orthodox Church and Joseph Semashko assisted to formulate ethnopolitical ideology of "Western Russia".