Magnitude (mathematics)

Magnitude as a concept dates to Ancient Greece and has been applied as a measure of distance from one object to another.

In physics, magnitude can be defined as quantity or distance.

An order of magnitude is typically defined as a unit of distance between one number and another's numerical places on the decimal scale.

[2] They did not consider negative magnitudes to be meaningful, and magnitude is still primarily used in contexts in which zero is either the smallest size or less than all possible sizes.

is usually called its absolute value or modulus, denoted by

The absolute value (or modulus) of z may be thought of as the distance of P from the origin of that space.

The formula for the absolute value of z = a + bi is similar to that for the Euclidean norm of a vector in a 2-dimensional Euclidean space:[5] where the real numbers a and b are the real part and the imaginary part of z, respectively.

Mathematically, a vector x in an n-dimensional Euclidean space can be defined as an ordered list of n real numbers (the Cartesian coordinates of P): x = [x1, x2, ..., xn].

This is equivalent to the square root of the dot product of the vector with itself: The Euclidean norm of a vector is just a special case of Euclidean distance: the distance between its tail and its tip.

Two similar notations are used for the Euclidean norm of a vector x: A disadvantage of the second notation is that it can also be used to denote the absolute value of scalars and the determinants of matrices, which introduces an element of ambiguity.

Examples include the loudness of a sound (measured in decibels), the brightness of a star, and the Richter scale of earthquake intensity.

In the natural sciences, a logarithmic magnitude is typically referred to as a level.

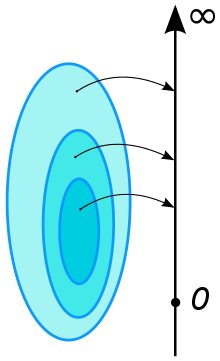

Orders of magnitude denote differences in numeric quantities, usually measurements, by a factor of 10—that is, a difference of one digit in the location of the decimal point.

In mathematics, the concept of a measure is a generalization and formalization of geometrical measures (length, area, volume) and other common notions, such as magnitude, mass, and probability of events.

These seemingly distinct concepts have many similarities and can often be treated together in a single mathematical context.

Measures are foundational in probability theory, integration theory, and can be generalized to assume negative values, as with electrical charge.