Loline alkaloid

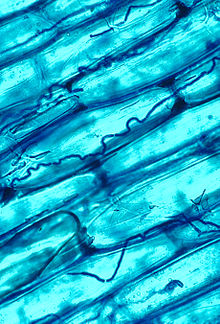

The lolines are insecticidal and insect-deterrent compounds that are produced in grasses infected by endophytic fungal symbionts of the genus Epichloë (anamorph species: Neotyphodium).

Lolines increase resistance of endophyte-infected grasses to insect herbivores, and may also protect the infected plants from environmental stresses such as drought and spatial competition.

Different substituents at the C-1 amine, such as methyl, formyl, and acetyl groups, yield loline species that have variable bioactivity against insects.

)[1] Studies in the 1950s and 1960s by Russian researchers established the name loline and identified the characteristic 2,7 ether bridge in its molecular structure.

Lolines are insecticidal and deterrent to a broad range of insects, including species in the Hemiptera, Coleoptera, Hymenoptera, Lepidoptera, and Blattodea, such as the bird cherry-oat aphid (genus Rhopalosiphum), large milkweed bug (Oncopeltus fasciatus), and American cockroach (Periplaneta americana).

By contrast, the lolines frequently accumulate to very high levels in grass tissues,[1] and were, therefore, initially associated also with toxicity to mammalian herbivores.

[10] Specifically, the lolines were thought to be responsible for toxic symptoms called fescue toxicosis displayed by livestock grazing on grasses infected by N.

[10] However, subsequently it was demonstrated that only the endophyte-produced ergot alkaloids are responsible for the symptoms of fescue toxicosis (or summer syndrome),[11] and not the lolines which, even at high doses, have only very small physiological effects on mammalians feeders.

Unlike the lolines, however, the senecio alkaloids exhibit strong hepatotoxicity,[13] owing to a double bond between C-1 and C-2 in their ring structure.

The lolines have been suggested to inhibit seed germination or growth of other plants (allelopathy),[14] and to increase resistance of infected grasses against drought, but such effects have not been substantiated under more natural conditions of cultivation or in habitats.

[16] Loline concentrations often increase in grass tissues regrown after defoliation and clipping of plants, suggesting an inducible defense response mechanism, involving both symbiotic partners.

[21] However, feeding studies with carbon isotope–labeled amino acids or related molecules in pure cultures of the loline-producing fungus N. uncinatum recently demonstrated that the loline alkaloid pathway is fundamentally different from that of the plant pyrrolizidines.