Long tail

It is a term used in online business, mass media, micro-finance (Grameen Bank, for example), user-driven innovation (Eric von Hippel), knowledge management, and social network mechanisms (e.g. crowdsourcing, crowdcasting, peer-to-peer), economic models, marketing (viral marketing), and IT Security threat hunting within a SOC (Information security operations center).

Chris Anderson's and Clay Shirky's articles highlight special cases in which we are able to modify the underlying relationships and evaluate the impact on the frequency of events.

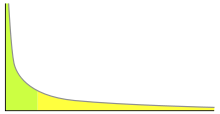

In those cases the infrequent, low-amplitude (or low-revenue) events – the long tail, represented here by the portion of the curve to the right of the 20th percentile – can become the largest area under the line.

This suggests that a variation of one mechanism (internet access) or relationship (the cost of storage) can significantly shift the frequency of occurrence of certain events in the distribution.

Anderson described the effects of the long tail on current and future business models beginning with a series of speeches in early 2004 and with the publication of a Wired magazine article in October 2004.

Anderson cites earlier research by Erik Brynjolfsson, Yu (Jeffrey) Hu, and Michael D. Smith, that showed that a significant portion of Amazon.com's sales come from obscure books that are not available in brick-and-mortar stores.

However, ten years later a book titled Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer was published and Touching the Void began to sell again.

This created a niche market for those who enjoy books about mountain climbing even though it is not considered a popular genre supporting the long tail theory.

[17] A subsequent study by Erik Brynjolfsson, Yu (Jeffrey) Hu, and Michael D. Smith[18] found that the long tail has grown longer over time, with niche books accounting for a larger share of total sales.

In a 2006 working paper titled "Goodbye Pareto Principle, Hello Long Tail",[20] Erik Brynjolfsson, Yu (Jeffrey) Hu, and Duncan Simester found that, by greatly lowering search costs, information technology in general and Internet markets in particular could substantially increase the collective share of hard-to-find products, thereby creating a longer tail in the distribution of sales.

On the supply side, the authors point out how e-tailers' expanded, centralized warehousing allows for more offerings, thus making it possible for them to cater to more varied tastes.

The authors also look toward the future to discuss second-order, amplified effects of Long Tail, including the growth of markets serving smaller niches.

Some recommenders (i.e. certain collaborative filters) can exhibit a bias toward popular products, creating positive feedback, and actually reduce the long tail.

The "crowds" of customers, users and small companies that inhabit the long-tail distribution can perform collaborative and assignment work.

An MIS Quarterly article by Gal Oestreicher-Singer and Arun Sundararajan shows that categories of books on Amazon.com which are more central and thus influenced more by their recommendation network have significantly more pronounced long-tail distributions.

An analysis based on this pure fashion model[29] indicates that, even for digital retailers, the optimal inventory may in many cases be less than the millions of items that they can potentially offer.

[30] Strategic partners receive the largest amount of diplomatic attention, while a long tail of remote states obtains just an occasional signal of peace.

[31] The internet has opened up larger territories to sell and provide its products without being confined to just the "local Markets" such as physical retailers like Target or even Walmart.

In following a long-tailed innovation strategy, the company is using the model to tap into a large group of users that are in the low-intensity area of the distribution.

[35] Among his conclusions is the insight that as innovation becomes more user-centered the information needs to flow freely, in a more democratic way, creating a "rich intellectual commons" and "attacking a major structure of the social division of labor".

This presents a unique opportunity for companies to leverage interactive and internet-based technologies to give their users a voice and enable them to participate in the innovation process.

By creating a platform for their users to share their ideas and feedback, companies can harness the power of collaborative innovation and stay ahead of the competition.

In situations where popularity is currently determined by the lowest common denominator, a long-tail model may lead to improvement in a society's level of culture.

At the end of the long tail, the conventional profit-making business model ceases to exist; instead, people tend to come up with products for varied reasons like expression rather than monetary benefit.

Television is a good example of this: Chris Anderson defines long-tail TV in the context of "content that is not available through traditional distribution channels but could nevertheless find an audience.

Often presented as a phenomenon of interest primarily to mass market retailers and web-based businesses, the long tail also has implications for the producers of content, especially those whose products could not – for economic reasons – find a place in pre-Internet information distribution channels controlled by book publishers, record companies, movie studios, and television networks.

[citation needed] One example of this is YouTube, where thousands of diverse videos – whose content, production value or lack of popularity make them inappropriate for traditional television – are easily accessible to a wide range of viewers.

The intersection of viral marketing, online communities and new technologies that operate within the long tail of consumers and business is described in the novel by William Gibson, Pattern Recognition.

[38] On his blog, Chris Anderson responded to the study, praising Elberse and the academic rigor with which she explores the issue but drawing a distinction between their respective interpretations of where the "head" and "tail" begin.

[39] Similar results were published by Serguei Netessine and Tom F. Tan, who suggest that head and tail should be defined by percentages rather than absolute numbers.