Low Countries theatre of the War of the First Coalition

[2] Although London had to recognise the United States' independence in 1783, this French foreign policy success came at a terrible financial cost, as the Bourbon kingdom struggled with enormous debts.

[8] Archbishop Joannes-Henricus de Franckenberg eventually called for armed resistance to defend the Catholic Church, and the secret society Pro aris et focis of Jan Frans Vonck and Jan-Baptist Verlooy began recruiting troops for a rebel army.

[8] The Brabantine rebel army defeated the Austrian forces at the Battle of Turnhout in October, and by January 1790, revolutionary Patriots led by Van der Noot and Vonck had taken control of most of the Southern Netherlands, and proclaimed the United Belgian States,[10] alongside the Liège Republic.

And just like the restored Orangist regime turned the Patriots into Francophile extremists, the Vonckists exiled to France forgot the nationalism out of which their movement had emerged, and eventually they would gleefully welcome the foreign revolution into their country.

'[14] Meanwhile, the failed June 1791 Flight to Varennes of king Louis XVI of France and his Austrian-born queen Marie Antoinette (Leopold II's sister) sparked more anti-royalist and republican sentiment, radicalising the French Revolution further.

With their differences settled and the Brabant and Liège Revolutions in the Southern Netherlands crushed, Austria and Prussia turned their attention to France, issuing the Declaration of Pillnitz (27 August 1791) that it was "in the common interest of all sovereigns of Europe" that no harm may come to the French royal family, and that if necessary, they would militarily intervene in order to protect the monarchy.

French commanders balanced between maintaining the security of the frontier, and clamours for victory (which would protect the regime in Paris) on the one hand, and the desperate condition of the army on the other, while they themselves were constantly under suspicion from the representatives.

The revolutionaries were forced on the defensive for months, losing Verdun and barely saving Thionville until the Coalition's unexpected defeat at Valmy (20 September 1792) turned the tables, and opened up a new opportunity for a northward invasion.

Britain agreed to invest a million pounds to finance a large Austrian army in the field plus a smaller Hanoverian corps, and dispatched an expeditionary force that eventually grew to approximately 20,000 British troops under the command of the king's younger son, the Duke of York.

Coburg was a reluctant leader and had hoped to end the war through diplomacy with Dumouriez, he even issued a proclamation declaring he was the "ally of all friends of order, abjuring all projects of conquest in the Emperors name", which he was immediately forced to recant by his political masters.

On the Rhine front the Prussians besieged Mainz, which held out from 14 April to 23 July 1793, and simultaneously mounted an offensive that swept through the Rhineland, mopping up small and disorganized elements of the French army.

Meanwhile, in Flanders, Coburg began investing the French fortifications at Condé-sur-l'Escaut, now reinforced by the Anglo-Hanoverian corps of the Duke of York and Prussian contingent of Alexander von Knobelsdorff.

The following week in the Tourcoing sector Dutch troops under the Hereditary Prince of Orange attempted to repeat the success but were roughly handled by Jourdan at Lincelles until extricated by the British Guards brigade.

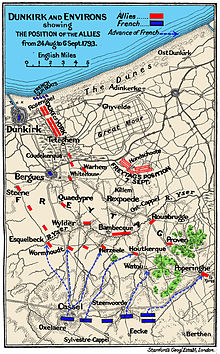

Houchard's plan had actually been to merely repulse the Duke of York so he could march south to relieve Le Quesnoy; on 13 September he defeated the Hereditary Prince at Menin (Menen), capturing 40 guns and driving the Dutch towards Bruges and Ghent, but three days later his forces were routed in turn by Beaulieu at Courtrai.

Further south Coburg meanwhile had captured Le Quesnoy on 11 September, enabling him to move forces north to assist York, and winning a signal victory over one of Houchard's Divisions at Avesnes-le-Sec.

The Duke of York was unable to offer much support as his command was greatly weakened, not only by the strain of the campaign, but also by Dundas in London, who began withdrawing troops to reassign to the West Indies.

Facing them the Armée du Nord was now under the command of Jean-Charles Pichegru, and had been greatly reinforced by conscripts as the result of the Levée en masse, giving the combined strength of the Armies of the North and Ardennes (excluding garrisons) as 200,000, nearly two to one of Coburg's force.

[36] On the Sambre front, after the previous two defeats, the divisions of Desjardin and Charbonnier had decided to capture Charleroi as a fortified base to anchor their position on the north bank, before trying to advance towards Mons.

With no further need to relieve Ypres, Coburg decided to concentrate most of his forces on the Sambre instead to drive Jourdan back, leaving York at Tournai and Clerfayt at Deinze to face Pichegru and cover the right.

Historian Digby Smith (1998) noted: 'By this stage of the war the court in Vienna was convinced that it was no longer worth the effort to try to hold on to the Austrian Netherlands and it is suspected that Coburg gave up the chance of a victory here so as to be able to pull out eastwards.

[citation needed] Meanwhile, Pichegru's Army of the North had been menacing the Duke of York's forces on the Scheldt at Oudenaarde, but was ordered at the end of June to move to the coast and capture the Flemish ports of Ostend (Oostende), Nieuport (Nieuwpoort) and Sluys (Sluis), then invade Holland.

[41] However, the next day, in the face of attacks from Jourdan (whose forces had been officially constituted as the Army of Sambre-and-Meuse on 29 June) all along the line from Braine-le-Comte to Gembloux, Coburg cancelled the agreement and retreated eastwards to Malines (Mechelen) and Louvain, vacating Brussels, and exposing York's left.

Two days later, York realised that Coburg had quietly ordered the Austrians protecting his left flank at Diest to retreat further east to Hasselt, exposing his rear to attack yet again without even informing him.

After the fall of Le Quesnoy and Landrecies to the French, Pichegru renewed his offensive on the 28th, obliging York to pull back to the line of the Aa River where he was attacked at Boxtel and persuaded to withdraw to the Meuse.

Brigades of Delmas' division, under Herman Willem Daendels and Pierre-Jacques Osten, moving at will, infiltrated the Dutch Water Line and captured fortifications and towns along a twenty-mile front.

Pitt, realizing that any imminent success on the continent was virtually impossible, at last gave the order to withdraw back to Britain, taking with them the remnants of the Dutch, German and Austrian troops that had retreated with them.

Prussia, too, had abandoned the Prince of Orange who it had saved in 1787, and already signed a separate peace with France on 5 April, surrendering all its own possessions on the west Rhine bank (Prussian Guelders, Moers and half of Cleves).

Some historians such as Alfred Burne (1949)[55] and Richard Glover (2008)[56] strongly challenge this characterisation, and York's defeat did not stop him from holding future military commands, including a long tenure as Commander-in-Chief of the Army (1795–1809; 1811–1827).

Varying and conflicting objectives of the commanders, poor coordination between the various nations, appalling conditions for the troops, and outside interference from civilian politicians such as Henry Dundas[57] for the British and Thugut for the Empire.

Many officers who would later rise to prominence received their baptism of fire on the fields of Flanders, including several of Napoleon's marshals – Bernadotte, Jourdan, Ney, MacDonald, Murat and Mortier.