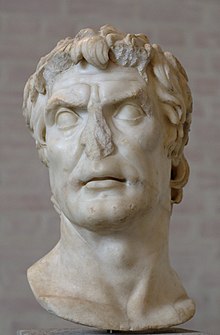

Sulla

Publius Cornelius Rufinus, one of Sulla's ancestors and also the last member of his family to be consul, was banished from the Senate after having been caught possessing more than 10 pounds of silver plate.

[15] One story, "as false as it is charming", relates that when Sulla was a baby, his nurse was carrying him around the streets, until a strange woman walked up to her and said, "Puer tibi et reipublicae tuae felix", which can be translated as, "The boy will be a source of luck to you and your state".

[21] The means by which Sulla attained the fortune which later would enable him to ascend the ladder of Roman politics are not clear; Plutarch refers to two inheritances, one from his stepmother (who loved him dearly) and the other from his mistress Nicopolis.

[36] The next year, Sulla was elected military tribune and served under Marius,[37] and assigned to treat with the Marsi, part of the Germanic invaders, he was able to negotiate their defection from the Cimbri and Teutones.

In memoirs related via Plutarch, he claimed this was because the people demanded that he first stand for the aedilate so – due to his friendship with Bocchus, a rich foreign monarch, – he might spend money on games.

[44] His term as praetor was largely uneventful, excepting a public dispute with Gaius Julius Caesar Strabo (possibly his brother-in-law) and his magnificent holding of the ludi Apollinares.

Despite initial difficulties, Sulla was successful with minimal resources and preparation; with few Roman troops, he hastily levied allied soldiers and advanced quickly into rugged terrain before routing superior enemy forces.

[55] The Cimbric war also revived Italian solidarity, aided by Roman extension of corruption laws to allow allies to lodge extortion claims.

[56] When the pro-Italian plebeian tribune Marcus Livius Drusus was assassinated in 91 BC while trying again to pass a bill extending Roman citizenship, the Italians revolted.

Killing Cluentius before the city's walls, Sulla then invested the town and for his efforts was awarded a grass crown, the highest Roman military honour.

[66] Buttressed by success against Rome's traditional enemies, the Samnites, and general Roman victory across Italy, Sulla stood for and was elected easily to the consulship of 88 BC; his colleague would be Quintus Pompeius Rufus.

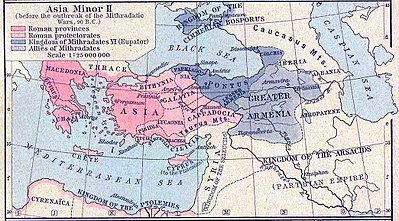

Beyond personal enmity, Caesar Strabo may also have stood for office because it was evident that Rome's relations with the Pontic king, Mithridates VI Eupator, were deteriorating and that the consuls of 88 would be assigned an extremely lucrative and glorious command against Pontus.

[72] Sulla became embroiled in a political fight against one of the plebeian tribunes, Publius Sulpicius Rufus,[69] on the matter of how the new Italian citizens were to be distributed into the Roman tribes for purposes of voting.

[96] While Rome was preparing to move against Pontus, Mithridates arranged the massacre of some eighty thousand Roman and Italian expatriates and their families – known today as the Asiatic vespers – and confiscated their properties.

[101] Discovering a weak point in the walls and popular discontent with the Athenian tyrant Aristion, Sulla stormed and captured Athens (except the Acropolis) on 1 March 86 BC.

[102] The Pontic casualties given in Plutarch and Appian, the main sources for the battles, are exaggerated; Sulla's report that he suffered merely fifteen losses is not credible.

[111] Faced with Fimbria's army in Asia, Lucullus' fleet off the coast, and internal unrest, Mithridates eventually met with Sulla at Dardanus in autumn 85 BC and accepted the terms negotiated by Archelaus.

[116] The general feeling in Italy, however, was decidedly anti-Sullan; many people feared Sulla's wrath and still held memories of his extremely unpopular occupation of Rome during his consulship.

[120] For 82 BC, the consular elections returned Gnaeus Papirius Carbo, in his third consulship, with the younger Gaius Marius, the son of the seven-time consul, who was then twenty-six.

[121][122] The remainder of 83 BC was dedicated to recruiting for the next year's campaign amid poor weather: Quintus Sertorius had raised a considerable force in Etruria, but was alienated from the consuls by the election of Gaius Marius' son rather than himself and so left to his praetorian province of Hispania Citerior; Sulla repudiated recognition of any treaties with the Samnites, whom he did not consider to be Roman citizens due to his rejection of Marius and Cinna's deal in 87 BC.

At the same time, the younger Marius sent word to assemble the Senate and purge it of suspected Sullan sympathisers: the urban praetor Lucius Junius Brutus Damasippus then had four prominent men killed at the ensuing meeting.

Proscribing or outlawing every one of those whom he perceived to have acted against the best interests of the Republic while he was in the east, Sulla ordered some 1,500 nobles (i.e. senators and equites) executed, although as many as 9,000 people were estimated to have been killed.

Sulla had total control of the city and Republic of Rome, except for Hispania (which the prominent Marian general Quintus Sertorius had established as an independent state).

This unusual appointment (used hitherto only in times of extreme danger to the city, such as during the Second Punic War, and then only for 6-month periods) represented an exception to Rome's policy of not giving total power to an individual.

From this distance, Sulla remained out of the day-to-day political activities in Rome, intervening only a few times when his policies were involved (e.g. the execution of Granius, shortly before his own death).

Ancient accounts of Sulla's death indicate that he died from liver failure or a ruptured gastric ulcer (symptomized by a sudden hemorrhage from his mouth, followed by a fever from which he never recovered), possibly caused by chronic alcohol abuse.

While Sulla's laws such as those concerning qualification for admittance to the Senate, reform of the legal system and regulations of governorships remained on Rome's statutes long into the principate, much of his legislation was repealed less than a decade after his death.

"[164] This duality, or inconsistency, made him very unpredictable and "at the slightest pretext, he might have a man crucified, but, on another occasion, would make light of the most appalling crimes; or he might happily forgive the most unpardonable offenses, and then punish trivial, insignificant misdemeanors with death and confiscation of property.

"[165] His excesses and penchant for debauchery could be attributed to the difficult circumstances of his youth, such as losing his father while he was still in his teens and retaining a doting stepmother, necessitating an independent streak from an early age.

The circumstances of his relative poverty as a young man left him removed from his patrician brethren, enabling him to consort with revelers and experience the baser side of human nature.