Lunar standstill

As a result, viewed from the middle latitudes, the Moon's altitude at upper culmination (the daily moment when the object appears to contact the observer's meridian) changes in two weeks from its maximum possible value to its minimum possible value above the horizon, due north or due south (depending on the observer's hemisphere).

The times of lunar standstills appear to have had special significance for the Bronze Age societies who built the megalithic monuments in Britain and Ireland.

A major lunar standstill occurs when the Moon's declination reaches a maximum monthly limit, at around 28.72° north or south, whereas a minor lunar standstill occurs when the declination reaches a minimum monthly limit, at around 18.13° north or south.

In other latitudes, the major lunar standstill featured constant scene illumination during the full Moon.

As Earth rotates on its axis, the stars in the night sky appear to follow circular paths around the celestial poles.

If viewed from a latitude of 50° N on Earth, any star with a declination of +50° would pass directly overhead (reaching the zenith at upper culmination) once every sidereal day (23 hours, 56 minutes, 4 seconds), whether visible at night or obscured in daylight.

Therefore, in June, in the Northern Hemisphere, the midday Sun is higher in the sky, and daytime then is longer than in December.

Consequently, in under a month, the Moon's altitude at upper culmination (when it contacts the observer's meridian) can shift from higher in the sky to lower above the horizon, and back.

At the minor lunar standstill, the Moon will change its declination during the tropical month from +18.3° to −18.3°, for a total range of 37°.

Then 9.3 years later, during the major lunar standstill, the Moon will change its declination during the month roughly from +28.6° to −28.6°, which totals 57° in range.

This range is enough to bring the Moon's altitude at culmination from high in the sky to low above the horizon in just two weeks (half an orbit).

For a latitude of 55° north or 55° south on Earth, the following table shows moonrise and moonset azimuths for the Moon's narrowest and widest arc paths across the sky.

The arc path of the full Moon generally reaches its widest in midwinter and its narrowest in midsummer.

The arc path of the first quarter moon generally reaches its widest in midspring and its narrowest in midautumn.

The arc path of the last quarter moon generally reaches its widest in midautumn and its narrowest in midspring.

The following table shows these altitudes at different times in the lunar nodal period for an observer at 55° north or 55° south.

The Moon's greatest declination occurs within a few months of these times, closer to an equinox, depending on its detailed orbit.

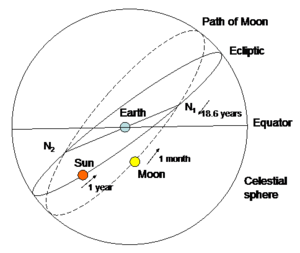

[7][8] A more detailed explanation is best considered in terms of the paths of the Sun and Moon on the celestial sphere, as shown in the first diagram.

Due to precession of the Moon's orbital plane, these crossing points, and the positions of eclipses, gradually shift around the ecliptic in a period of 18.6 years.

The Sun's gravitational attraction on the Moon pulls it toward the plane of the ecliptic, causing a slight wobble of about 9 arcmin within a 173-day period.

The next highest was at 07:36 on 4 April, when it reached +28:42:53.9 However, these dates and times do not represent the maxima and minima for observers on the Earth's surface.

For example, after taking refraction and parallax into account, the observed maximum on 15 September in Sydney, Australia, was several hours earlier, and then occurred in daylight.

The table shows the major standstills that were actually visible (i.e. not in full daylight, and with the Moon above the horizon) from both London, UK, and Sydney, Australia.