Trumpism

Politicians labeled as Trumpist by news agencies include Nigel Farage of the United Kingdom, Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan of Turkey, Viktor Orbán of Hungary, Rodrigo Duterte and Bongbong Marcos of the Philippines, Shinzo Abe of Japan, Vladimir Putin of Russia, Yoon Suk Yeol of South Korea, Javier Milei of Argentina, Alexander Lukashenko of Belarus, and Prabowo Subianto of Indonesia.

"[75][note 4] Exit polling data suggests the campaign was successful at mobilizing the "white disenfranchised",[76] the lower- to working-class European-Americans who are experiencing growing social inequality and who often have stated opposition to the American political establishment.

[88] Disputing the view that the surge of support for Trumpism and Brexit is a new phenomenon, political scientist Karen Stenner and social psychologist Jonathan Haidt state that the far-right populist wave ... did not in fact come out of nowhere.

"[99] Social psychologists Theresa Vescio and Nathaniel Schermerhorn note that "In his 2016 presidential campaign, Trump embodied HM [hegemonic masculinity] while waxing nostalgic for a racially homogenous past that maintained an unequal gender order.

[124] Historian Stephen Jaeger traces the history of admonitions against becoming beholden religious courtiers back to the 11th century, with warnings of curses placed on holy men barred from heaven for taking too "keen an interest in the affairs of the state.

[127] Pope Pius II opposed the clergy's presence at court, believing it was difficult for a Christian courtier to "rein in ambition, suppress avarice, tame envy, strife, wrath, and cut off vice, while standing in the midst of these [very] things."

"[132] From Jeffress's reading, government's purpose is as a "strongman to protect its citizens against evildoers", adding: "I don't care about that candidate's tone or vocabulary, I want the meanest toughest son of a you-know-what I can find, and I believe that is biblical.

[136] Like Jeffress, Richard Land refused to cut ties with Trump after his reaction to the Charlottesville white supremacist rally, with the explanation that "Jesus did not turn away from those who may have seemed brash with their words or behavior," adding that "now is not the time to quit or retreat, but just the opposite—to lean in closer.

To Hochschild, this explains the paradox raised by Thomas Frank's book What's the Matter with Kansas?, an anomaly which motivated her five-year immersive research into the emotional dynamics of the Tea Party movement which she believes has mutated into Trumpism.

[153] She thinks Trump's approach towards his audience creates group cohesiveness by exploiting a crowd phenomenon Emile Durkheim called "collective effervescence", "a state of emotional excitation felt by those who join with others they take to be fellow members of a moral or biological tribe ... to affirm their unity and, united, they feel secure and respected.

[174] According to civil rights lawyer Burt Neuborne and political theorist William E. Connolly, Trumpist rhetoric employs tropes similar to those used by fascists in Germany[177] to persuade citizens (at first a minority) to give up democracy, by using a barrage of falsehoods, half-truths, personal invective, threats, xenophobia, national-security scares, religious bigotry, white racism, exploitation of economic insecurity, and a never-ending search for scapegoats.

[178] Neuborne found twenty parallel practices,[179] such as creating what amounts to an "alternate reality" in adherents' minds, through direct communications, by nurturing a fawning mass media and by deriding scientists to erode the notion of objective truth;[180] organizing carefully orchestrated mass rallies;[181] attacking judges when legal cases are lost;[182] using lies, half-truths, insults, vituperation and innuendo to marginalize, demonize and destroy opponents;[181] making jingoistic appeals to ultranationalist fervor;[181] and promising to stop the flow of "undesirable" ethnic groups who are made scapegoats for the nation's ills.

[183] Connolly presents a similar list in his book Aspirational Fascism (2017), adding comparisons of the integration of theatrics and crowd participation with rhetoric, involving grandiose bodily gestures, grimaces, hysterical charges, dramatic repetitions of alternate reality falsehoods, and totalistic assertions incorporated into signature phrases that audiences are encouraged to join in chanting.

"[207] Media scholar Olivier Jutel notes that, "Affect is central to the brand strategy of Fox which imagined its journalism not in terms of servicing the rational citizen in the public sphere but in 'craft[ing] intensive relationships with their viewers' (Jones, 2012: 180) in order to sustain audience share across platforms.

[220] Drawing on Harry G. Frankfurt's book On Bullshit, political science professor Matthew McManus argues that Trump as a bullshitter whose sole interest is to persuade, and not a liar (e.g. Richard Nixon) who takes the power of truth seriously and so deceitfully attempts to conceal it.

[223] Connolly points to the similarities of such reality-bending gaslighting with fascist and post Soviet techniques of propaganda including Kompromat (scandalous material), stating that "Trumpian persuasion draws significantly upon the repetition of Big Lies.

Despite disparate and inconsistent beliefs and ideologies, a coalition of such followers can become cohesive and broad in part because each individual "compartmentalizes" their thoughts[233] and they are free to define their sense of the threatened tribal in-group[234] in their own terms, whether it is predominantly related to their cultural or religious views[235] (e.g. the mystery of evangelical support for Trump), nationalism[236] (e.g. the Make America Great Again slogan), or their race (maintaining a white majority).

[242] Quoting comments from participants in focus groups made up of people who had voted for Democrat Obama in 2012 but flipped to Trump in 2016, pollster Diane Feldman noted the anti-government, anti-coastal-elite anger: "'They think they're better than us, they're P.C., they're virtue-signallers.'

"[246] McAdams points out the audience gets to vicariously share in the sense of dominance due to the parasocial bonding that his performance produces for his fans, as shown by Shira Gabriel's research studying the phenomenon in Trump's role in The Apprentice.

[257] Social theory scholar John Cash notes that disaster narratives of impending horrors have a broad audience, pointing to a 2010 Pew study which found that 41 percent of those in the US think that the world will probably be destroyed by the middle of the century.

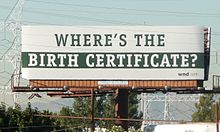

"[258] Cash compares Alice in Wonderland to Trump's ability to seemingly embrace disparate fantasies in a series of contradictory tweets and pronouncements, for example appearing to encourage the "neo-Nazi protestors" after Charlottesville or for audiences with felt grievances about America's first black president, the claim that Obama wiretapped him.

[261] Conservative culture commentator David Brooks observes that under Trump, this post-truth mindset, heavily reliant on conspiracy themes, came to dominate Republican identity, providing its believers a sense of superiority since such insiders possess important information most people do not have.

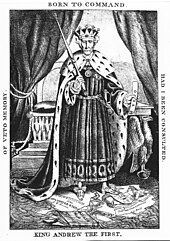

[36] Other research has argued that Trump's personality cult revolves around an "all-powerful, charismatic figure, contributing to a social milieu at risk for the erosion of democratic principles and the rise of fascism" based on the analysis of psycoanalists and sociopolitical historians.

Surveying research of how Trumpist communication is well suited to social media, Brian Ott writes that, "commentators who have studied Trump's public discourse have observed speech patterns that correspond closely to what I identified as Twitter's three defining features [Simplicity, impulsivity, and incivility].

[309] They explained that such discourse "[involves] efforts to provoke visceral responses (e.g., anger, righteousness, fear, moral indignation) from the audience through the use of overgeneralizations, sensationalism, misleading or patently inaccurate information, ad hominem attacks, and partial truths about opponents, who may be individuals, organizations, or entire communities of interest (e.g., progressives or conservatives) or circumstance (e.g., immigrants).

"[310] Due to Facebook's and Twitter's narrowcasting environment in which outrage discourse thrives,[note 20] Trump's employment of such messaging at almost every opportunity was from O'Callaghan's account extremely effective because tweets and posts were repeated in viral fashion among like minded supporters, thereby rapidly building a substantial information echo chamber,[312] a phenomenon Cass Sunstein identifies as group polarization,[313] and other researchers refer to as a kind of self re-enforcing homophily.

"[319] Media critic Alex Ross is similarly alarmed, observing, "Silicon Valley monopolies have taken a hands-off, ideologically vacant attitude toward the upswelling of ugliness on the Internet," and that "the failure of Facebook to halt the proliferation of fake news during the [Trump vs. Clinton] campaign season should have surprised no one.

On Morris's view, Trumpism also shares similarities with the post-World War I faction of the progressive movement which catered to a conservative populist recoil from the looser morality of the cosmopolitan cities and America's changing racial complexion.

Some of these tactics and views are right-wing populism, demonization of the press, subversion of well-established and proven facts through the big lie (both historical and scientific), democratic backsliding such as dismantling judicial and political mechanisms; portraying systematic issues such as sexism or racism as isolated incidents, and crafting an ideal citizen.

[402][403] Trump's proposals during his second presidency to expand the United States by acquiring Canada, Greenland, and the Panama Canal were described by CNN as part of his nationalist "America First" agenda and having "modern echoes of the 19th century doctrine of Manifest Destiny".