Aufbau principle

In atomic physics and quantum chemistry, the Aufbau principle (/ˈaʊfbaʊ/, from German: Aufbauprinzip, lit.

'building-up principle'), also called the Aufbau rule, states that in the ground state of an atom or ion, electrons first fill subshells of the lowest available energy, then fill subshells of higher energy.

If double occupation does occur, the Pauli exclusion principle requires that electrons that occupy the same orbital must have different spins (+1⁄2 and −1⁄2).

Thus subshells are filled in the order of increasing energy, using two general rules to help predict electronic configurations: A version of the aufbau principle known as the nuclear shell model is used to predict the configuration of protons and neutrons in an atomic nucleus.

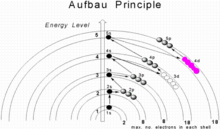

[1] In neutral atoms, the approximate order in which subshells are filled is given by the n + l rule, also known as the: Here n represents the principal quantum number and l the azimuthal quantum number; the values l = 0, 1, 2, 3 correspond to the s, p, d, and f subshells, respectively.

The subshell ordering by this rule is 1s, 2s, 2p, 3s, 3p, 4s, 3d, 4p, 5s, 4d, 5p, 6s, 4f, 5d, 6p, 7s, 5f, 6d, 7p, 8s, 5g, ... For example, thallium (Z = 81) has the ground-state configuration 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p6 4s2 3d10 4p6 5s2 4d10 5p6 6s2 4f14 5d10 6p1[4] or in condensed form, [Xe] 6s2 4f14 5d10 6p1.

On a related note, writing configurations in this way emphasizes the outermost electrons and their involvement in chemical bonding.

[6] The Madelung energy ordering rule applies only to neutral atoms in their ground state.

There are twenty elements (eleven in the d-block and nine in the f-block) for which the Madelung rule predicts an electron configuration that differs from that determined experimentally, although the Madelung-predicted electron configurations are at least close to the ground state even in those cases.

All these exceptions are not very relevant for chemistry, as the energy differences are quite small[7] and the presence of a nearby atom can change the preferred configuration.

[9] They occur as the result of interelectronic repulsion effects;[7][8] when atoms are positively ionised, most of the anomalies vanish.

Element 121, starting the g-block, should be an exception in which the expected 5g electron is transferred to 8p (similarly to lawrencium).

Although in hydrogen there is no energy difference between subshells with the same principal quantum number n, this is not true for the outer electrons of other atoms.

Wolfgang Pauli's model of the atom, including the effects of electron spin, provided a more complete explanation of the empirical aufbau rules.

[12] A periodic table in which each row corresponds to one value of n + l (where the values of n and l correspond to the principal and azimuthal quantum numbers respectively) was suggested by Charles Janet in 1928, and in 1930 he made explicit the quantum basis of this pattern, based on knowledge of atomic ground states determined by the analysis of atomic spectra.

Janet "adjusted" some of the actual n + l values of the elements, since they did not accord with his energy ordering rule, and he considered that the discrepancies involved must have arisen from measurement errors.

As it happens, the actual values were correct and the n + l energy ordering rule turned out to be an approximation rather than a perfect fit, although for all elements that are exceptions the regularised configuration is a low-energy excited state, well within reach of chemical bond energies.

Klechkowski proposed a theoretical explanation for the importance of the sum n + l, based on the Thomas–Fermi model of the atom.

[18] ' The full Madelung rule was derived from a similar potential in 1971 by Yury N. Demkov and Valentin N.

, the zero-energy solutions to the Schrödinger equation for this potential can be described analytically with Gegenbauer polynomials.

For example, in the fourth row of the periodic table, the Madelung rule indicates that the 4s subshell is occupied before the 3d.