Major urinary proteins

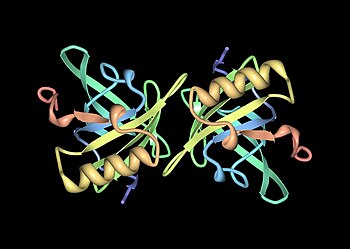

Mup proteins form a characteristic glove shape, encompassing a ligand-binding pocket that accommodates specific small organic chemicals.

However, as secreted proteins they play multiple roles in chemical communication between animals, functioning as pheromone transporters and stabilizers in rodents and pigs.

[3] Between 1932 and 1933 a number of scientists, including Thomas Addis, independently reported the surprising finding that some healthy rodents have protein in their urine.

[7][8] It was found that the proteins are primarily made in the liver of males and secreted through the kidneys into the urine in large quantities (milligrams per day).

However, this occurred independently of the duplications in mice, meaning that both rodent species expanded their Mup gene families separately, but in parallel.

[1][23] Most other mammals studied, including the pig, cow, cat, dog, bushbaby, macaque, chimpanzee and orangutan, have a single Mup gene.

[25] Consequently, they form a characteristic glove shape, encompassing a cup-like pocket that binds small organic chemicals with high affinity.

[27][28][29] These are all urine-specific chemicals that have been shown to act as pheromones—molecular signals excreted by one individual that trigger an innate behavioural response in another member of the same species.

[1][14] Isothermal titration calorimetry studies performed with Mups and associated ligands (pyrazines,[36][37] alcohols,[38][39] thiazolines,[40][28] 6-hydroxy-6-methyl-3-heptanone,[41] and N-phenylnapthylamine,[42][43]) revealed an unusual binding phenomena.

The active site has been found to be suboptimally hydrated, resulting in ligand binding being driven by enthalpic dispersion forces.

Mup proteins have been shown to promote puberty and accelerate the estrus cycle in female mice, inducing the Vandenbergh and Whitten effects.

[38][44] However, in both cases the Mups had to be presented to the female dissolved in male urine, indicating that the protein requires some urinary context to function.

The precise mechanism driving this difference between the sexes is complex, but at least three hormones—testosterone, growth hormone and thyroxine—are known to positively influence the production of Mups in mice.

[20] However, unlike wild mice, different individuals from the same strain express the same protein pattern, an artifact of many generations of inbreeding.

[49][50] One unusual Mup is less variable than the others: it is consistently produced by a high proportion of wild male mice and is almost never found in female urine.

[52][53] Taken together, the complex patterns of Mups produced has the potential to provide a range of information about the donor animal, such as gender, fertility, social dominance, age, genetic diversity or kinship.

[54] In the house mouse, the major MUP gene cluster provides a highly polymorphic scent signal of genetic identity.

[75] Mup genes from other mammals also encode allergenic proteins, for example Fel d 4 is primarily produced in the submandibular salivary gland and is deposited onto dander as the cat grooms itself.

[13] Likewise, Equ c 1 (Equus caballus allergen 1; Q95182) is the protein product of a horse Mup gene that is found in the liver, sublingual and submaxillary salivary glands.

Scientists found that genetically induced obese, diabetic mice produce thirty times less Mup RNA than their lean siblings.

[77] When they delivered Mup protein directly into the bloodstream of these mice, they observed an increase in energy expenditure, physical activity and body temperature and a corresponding decrease in glucose intolerance and insulin resistance.

In this case, the presence of Mups in the bloodstream of mice restricted glucose production by directly inhibiting the expression of genes in the liver.