Marcellina (Gnostic)

Marcellina was an early Christian Carpocratian religious leader in the mid-second century AD known primarily from the writings of Irenaeus and Origen.

Like other Carpocratians, Marcellina and her followers believed in antinomianism, also known as libertinism, the idea that obedience to laws and regulations is unnecessary in order to attain salvation.

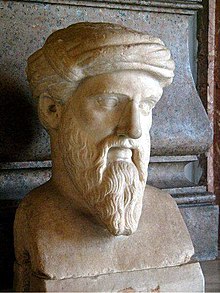

The Marcellians in particular are reported to have branded their disciples on the insides of their right earlobes and venerated images of Jesus as well as Greek philosophers such as Pythagoras, Plato, and Aristotle.

[2] A creed that may have been recited at Christian initiation ceremonies is quoted by the apostle Paul in Galatians 3:28: "There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus.

[3] Female religious leaders like Marcellina were not favored by proto-orthodox theologians, who accused them of madness, unchastity, and demonic possession.

[3] As a Carpocratian, Marcellina taught the doctrine of antinomianism, or libertinism,[5][6] which holds that only faith and love are necessary to attain salvation and that all other perceived requirements, especially obedience to laws and regulations, are unnecessary.

[6] The Church Father Irenaeus (c. 130 – c. 202) records in his apologetic treatise Adversus Haereses: Others of them [i.e., the Carpocratians] employ outward marks, branding their disciples inside the lobe of the right ear.

They also possess images, some of them painted, and others formed from different kinds of material; while they maintain that a likeness of Christ was made by Pilate at that time when Jesus lived among them.

[12] Anne McGuire states that it is unclear whether this description of Marcellina in relation to Carpocrates is a result of Irenaeus's own patriarchal worldview, the actual relationship between her and him, or both.

[10][7] While Irenaeus interprets this as a sign of Marcellina's heterodox teaching,[14] to any non-Christian Roman, it would have actually made her seem far less aberrant than proto-orthodox Christians.

[15] She also argues that the Marcellians' busts of Jesus and other philosophers may have survived long after their sect declined,[15] observing that, nearly a century later, the Roman emperor Alexander Severus (reigned 222 – 235) is said to have possessed a collection of portrait busts of various philosophers, religious figures, and historical figures including Jesus, Orpheus, Apollonius of Tyana, Alexander the Great, and Abraham.

[20] Also, Hippolytus of Rome, who relied on Irenaeus as a source, references that another sect known as the Naassenes "call themselves 'gnostics' in their own way, as if they alone have drunk from the amazing acquaintance of the Perfect and Good.

[23] Irenaeus states that, among members of his own congregation in Gaul in the 180s, "we have no fellowship with them either in doctrine or in morals or in our daily social life",[23] but this statement should not be taken to apply to Christians living in Rome over twenty years prior.

[23] Robert M. Grant identifies the anti-Gnostic writings of Polycarp and Justin Martyr as partially an indirect reaction against Marcellina and her permissive moral teachings.