Maria: or, The Wrongs of Woman

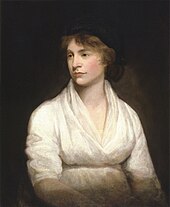

It focuses on the societal rather than the individual "wrongs of woman" and criticizes what Wollstonecraft viewed as the patriarchal institution of marriage in eighteenth-century Britain and the legal system that protected it.

Such themes, coupled with the publication of Godwin's scandalous Memoirs of Wollstonecraft's life, made the novel unpopular at the time it was published.

She befriends one of her attendants in the asylum, an impoverished, lower-class woman named Jemima, who, after realizing that Maria is not mad, agrees to bring her a few books.

Darnford reveals that he has had a debauched life; waking up in the asylum after a night of heavy drinking, he has been unable to convince the doctors to release him.

[6] In her pieces for the Analytical Review, Wollstonecraft developed a set of criteria for what constitutes a good novel: A good tragedy or novel, if the criterion be the effect which it has on the reader, is not always the most moral work, for it is not the reveries of sentiment, but the struggles of passion — of those human passions, that too frequently cloud the reason, and lead mortals into dangerous errors ... which raise the most lively emotions, and leave the most lasting impression on the memory; an impression rather made by the heart than the understanding: for our affections are not quite voluntary as the suffrages of reason.

[8] Thus it is surprising that The Wrongs of Woman draws inspiration from works such as Ann Radcliffe's A Sicilian Romance (1790) and relies on gothic conventions such as the literal and figurative "mansion of despair" to which Maria is consigned.

[9] As Wollstonecraft herself writes in the "Preface" to The Wrongs of Woman: In many instances I could have made the incidents more dramatic, would I have sacrificed my main object, the desire of exhibiting the misery and oppression, peculiar to women, that arise out of the partial laws and customs of society.

Wollstonecraft's novel argues along with others, such as Mary Hays's Memoirs of Emma Courtney (1796), that women are the victims of constant and systematic injustice.

Wollstonecraft added to the reality of her philosophical text by quoting from familiar literature, such as Shakespeare, alluding to important historical events, and referencing relevant facts.

Unlike Wollstonecraft's first novel, Mary: A Fiction (1788), The Wrongs of Woman offers solutions to these problems, namely an empowering female sexuality, a purpose-filled maternal role, and the possibility of a feminism that crosses class boundaries.

[17] Moreover, Maria's body is bought and sold like a slave's: she is worth £5,000 on the open marriage market and her new husband attempts to sell her into prostitution.

[19] "Wollstonecraft's fundamental insight in Maria", according to scholar Mary Poovey, "concerns the way in which female sexuality is defined or interpreted—and, by extension, controlled—by bourgeois institutions.

Thus historians have credited the discourse of sensibility and those who promoted it with the increased humanitarian efforts, such as the movement to abolish the slave trade, of the eighteenth century.

As feminist scholar Mitzi Myers has observed, Wollstonecraft is usually described as an "enlightened philosopher strenuously advocating the cultivation of reason as the guide to both self-realization and social progress", but her works do not unambiguously support such a model of selfhood.

In this interpretation, Maria's narrative is read as a parody of sentimental fiction that aims to demonstrate the "wrongs" that women inflict upon themselves when they overindulge in sensibility.

In The Wrongs of Woman, however, she accepts, relishes, and uses the sexualized female body as a medium of communication: Maria embraces her lust for Darnford and establishes a relationship with him.

[36] However, she later realizes his duplicity: [George] continued to single me out at the dance, press my hand at parting, and utter expressions of unmeaning passion, to which I gave a meaning naturally suggested by the romantic turn of my thoughts. ...

They argue that Wollstonecraft is not portraying female sexuality as inherently detrimental, as she had in Mary and the Rights of Woman, rather she is criticizing the directions it often takes.

[43] Jemima is the most fleshed out of the lower-class women in the novel; through her Wollstonecraft refuses to accept the submissiveness traditionally associated with femininity and expresses a frustrated anger that would have been viewed as unseemly in Maria.

"[45] As Wollstonecraft scholar Barbara Taylor comments, "Maria's relationship with Jemima displays something of the class fissures and prejudices that have marked organised feminist politics from their inception.

[47] While some scholars emphasize The Wrongs of Woman's criticism of the institution of marriage and the laws restricting women in the eighteenth century, others focus on the work's description of "the experience of being female, with the emotional violence and intellectual debilitation" that accompanies it (emphasis in original).

Women such as Jemima are reduced to hard physical labor, stealing, begging, or prostituting themselves in order to survive; they are demeaned by this work and think meanly of themselves because of it.

[51] Because male-female relationships are inherently unequal in her society, Wollstonecraft endeavours to formulate a new kind of friendship in The Wrongs of Woman: motherhood and sisterhood.

With Jemima's rescue of Maria, Wollstonecraft appears to reject the traditional romantic plot and invent a new one, necessitated by the failure of society to grant women their natural rights.

[57] The Posthumous Works, of which The Wrongs of Woman was the largest part, had a "reasonably wide audience" when it was published in 1798, but it "was received by critics with almost universal disfavor".

[58] This was in large part because the simultaneous release of Godwin's Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman revealed Wollstonecraft's illegitimate child and her love affairs.

The Anti-Jacobin Review, attacking both Wollstonecraft and her book as well as Godwin's Political Justice and Memoirs, wrote: The restrictions upon adultery constitute, in Maria's opinion, A MOST FLAGRANT WRONG TO WOMEN.

Such is the moral tendency of this work, such are the lessons which may be learned from the writings of Mrs. Wollstonecraft; such the advantages which the public may derive from this performance given to the world by Godwin, celebrated by him, and perfectly consonant to the principles of his Political Justice.—But as there have been writers, who have in theory promulgated opinions subversive of morality, yet in their conduct have not been immoral, Godwin has laboured to inform the world, that the theory of Mrs. Wollstonecraft was reduced to practice; that she lived and acted, as she wrote and taught.

[Footnote in original: We could point out some of this lady's pupils, who have so far profited by the instructions received from her, as to imitate her conduct, and reduce her principles to practice.]

[39] While Wollstonecraft's arguments in The Wrongs of Woman may appear commonplace in light of modern feminism, they were "breathtakingly audacious" during the late eighteenth century: "Wollstonecraft's final novel made explosively plain what the Rights of Woman had only partially intimated: that women's entitlements — as citizens, mothers, and sexual beings — are incompatible with a patriarchal marriage system.