Marxist historiography

It has had unique trajectories of development in the West, the Soviet Union, and in India, as well as in the pan-Africanist and African-American traditions, adapting to these specific regional and political conditions in different ways.

[7] Friedrich Engels' (1820–1895) most important historical contribution to the development of Marxist historiography was Der Deutsche Bauernkrieg (The German Peasants' War, 1850), which analysed social warfare in early Protestant Germany in terms of emerging capitalist classes.

Karl Marx (1818–1883) contributed important works on social and political history, including The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon (1852), The Communist Manifesto (1848), The German Ideology (written in 1845, published in 1932), and those chapters of Das Kapital (1867–1894) dealing with the historical emergence of capitalists and proletarians from pre-industrial English society.

History moved by the sheer force of human labour, and all theories of divine nature were a concoction of the ruling powers to keep the working people in check.

"[10] As one might expect, Marxist history not only begins with labour, it ends in production: "history does not end by being resolved into "self-consciousness" as "spirit of the spirit," but that in it at each stage there is found a material result: a sum of productive forces, a historically created relation of individuals to nature and to one another, which is handed down to each generation from its predecessor..."[11] For further, and much more comprehensive, information on this topic, see historical materialism.

Marx's theory of history locates historical change in the rise of class societies and the way humans labour together to make their livelihoods.

Marx argues that the introduction of new technologies and new ways of doing things to improve production eventually lead to new social classes which in turn result in political crises which can threaten the established order.

Marx's view of history is in contrast to the commonplace notion that the rise and fall of kingdoms, empires and states, can broadly be explained by the actions, ambitions and policies of the people at the top of society; kings, queens, emperors, generals, or religious leaders.

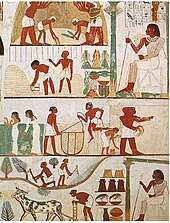

The main modes of production that Marx identified generally include primitive communism, slave society, feudalism, mercantilism, and capitalism.

The discovery of the materialist conception of history, or rather, the consistent continuation and extension of materialism into the domain of social phenomenon, removed two chief defects of earlier historical theories.

In the first place, they at best examined only the ideological motives of the historical activity of human beings, without grasping the objective laws governing the development of the system of social relations.

[25] All constituent features of a society (social classes, political pyramid and ideologies) are assumed to stem from economic activity, forming what is considered as the base and superstructure.

Those newly formed social organizations can then act again upon both parts of the base and superstructure so that rather than being static, the relationship is dialectic, expressed and driven by conflicts and contradictions.

In a letter to editor of the Russian newspaper paper Otetchestvennye Zapiskym (1877),[29] he explained that his ideas are based upon a concrete study of the actual conditions in Europe.

[30] To summarize, history develops in accordance with the following observations: Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels worked in relative isolation together outside the larger mainstream.

He was profoundly interested in the issue of the enclosure of land in the English countryside in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and Max Weber's thesis on the connection between the appearance of Protestantism and the rise of capitalism.

It became a highly influential cluster of British Marxist historians, who shared a common interest in and contributed to history from below and class structure in early capitalist society.

While some members of the group (most notably Christopher Hill [1912–2003] and E. P. Thompson [1924–1993]) left the CPGB after the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, the common points of British Marxist historiography continued in their works.

In his preface to this book, Thompson set out his approach to writing history from below: I am seeking to rescue the poor stockinger, the Luddite cropper, the "obsolete" hand-loom weaver, the "Utopian" artisan, and even the deluded follower of Joanna Southcott, from the enormous condescension of posterity.

Their aspirations were valid in terms of their own experience; and, if they were casualties of history, they remain, condemned in their own lives, as casualties.Thompson's work was also significant because of the way he defined "class".

He opened the gates for a generation of labour historians, such as David Montgomery (1927–2011) and Herbert Gutman (1928–1985), who made similar studies of the American working classes.

The Black Jacobins was the first professional historical account of the greatest and only successful slave revolt in colonial American history, the Haitian Revolution.

In addition, Leninism argued that a vanguard party was required to lead the working class in the revolution that would overthrow capitalism and replace it with socialism.

Furthermore, the Communist Party – considered to be the vanguard of the working class – was given the role of permanent leading force in society, rather than a temporary revolutionary organization.

[40][41] This work crystallised the piatichlenka or five acceptable moments of history in terms of vulgar dialectical materialism: primitive-communism, slavery, feudalism, capitalism and socialism.

Some world-systems analysts, such as Janet Abu-Lughod, claim that analysis of Kondratiev waves shows that capitalism first arose in Song dynasty China, although widespread trade was subsequently disrupted and then curtailed.

The Japanese scholar Tanigawa Michio, writing in the 1970s and 1980s, set out to revise the generally Marxist views of China prevalent in post-war Japan.

Tanigawa reviewed the applications of these theories in Japanese writings about Chinese history and then tested them by analysing the Six Dynasties 220–589 CE period, which Marxist historians saw as feudal.

[45] There was a gradual relaxation of Marxist interpretation after the death of Mao in 1976,[46] which was accelerated after the Tian'anmen Square protest and other revolutions in 1989, which damaged Marxism's ideological legitimacy in the eyes of Chinese academics.

[62][63][64][65] Since the late 1990s, Hindu nationalist scholars especially have polemicized against the Marxian tradition in India for neglecting what they believe to be the country's 'illustrious past' based on Vedic-puranic chronology.