Mathematicism

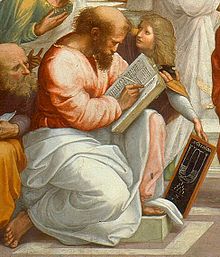

It is clear that numbers held a particular importance for the Pythagorean school, although it was the later work of Plato that attracts the label of mathematicism from modern philosophers.

Although we do not have writings of Pythagoras himself, good evidence that he pioneered the concept of mathematicism is given by Plato, and summed up in the quotation often attributed to him that "everything is mathematics".

Nevertheless modern scholars debate whether this numerology was taught by Pythagoras himself or whether it was original to the later philosopher of the Pythagorean school, Philolaus of Croton.

[13] In summary, therefore, Mathematical Platonism can be reduced to three propositions: It is again not clear the extent to which Plato held to these views himself but they were associated with the Platonist school.

[14]Although mathematical methods of investigation have been used to establish meaning and analyse the world since Pythagoras, it was Descartes who pioneered the subject as epistemology, setting out Rules for the Direction of the Mind.

He proposed that method, rather than intuition, should direct the mind, saying: So blind is the curiosity with which mortals are possessed that they often direct their minds down untrodden paths, in the groundless hope that they will chance upon what they are seeking, rather like someone who is consumed with such a senseless desire to discover treasure that he continually roams the streets to see if he can find any that a passerby might have dropped [...] By 'a method' I mean reliable rules which are easy to apply, and such that if one follows them exactly, one will never take what is false to be true or fruitlessly expend one's mental efforts, but will gradually and constantly increase one's knowledge till one arrives at a true understanding of everything within one's capacity In the discussion of Rule Four,[16] Descartes' describes what he calls mathesis universalis:[...] I began my investigation by inquiring what exactly is generally meant by the term 'mathematics' and why it is that, in addition to arithmetic and geometry, sciences such as astronomy, music, optics, mechanics, among others, are called branches of mathematics.

[4] Following Descartes, Leibniz attempted to derive connections between mathematical logic, algebra, infinitesimal calculus, combinatorics, and universal characteristics in an incomplete treatise titled "Mathesis Universalis", published in 1695.

[citation needed] Following on from Leibniz, Benedict de Spinoza and then various 20th century philosophers, including Bertrand Russell, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and Rudolf Carnap have attempted to elaborate and develop Leibniz's work on mathematical logic, syntactic systems and their calculi and to resolve problems in the field of metaphysics.

Leibniz attempted to work out the possible connections between mathematical logic, algebra, infinitesimal calculus, combinatorics, and universal characteristics in an incomplete treatise titled "Mathesis Universalis" in 1695.

[20] As anthropologist Emily Martin notes:[21] Tackling mathematics, the realm of symbolic life perhaps most difficult to regard as contingent on social norms, Wittgenstein commented that people found the idea that numbers rested on conventional social understandings "unbearable".The Principia Mathematica is a three-volume work on the foundations of mathematics written by the mathematicians Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell and published in 1910, 1912, and 1913.