Maximilien Robespierre

In 1786 Robespierre passionately addressed inequality before the law, criticising the indignities faced by illegitimate or natural children, and later denouncing practices like lettres de cachet (imprisonment without a trial) and the marginalisation of women in academic circles.

[35] Robespierre's social circle expanded to include influential figures such as the lawyer Martial Herman, the officer and engineer Lazare Carnot and the teacher Joseph Fouché, all of whom would hold significance in his later endeavours.

In August 1788, King Louis XVI declared new elections for all provinces and summoned the Estates-General to convene on 1 May 1789, aiming to address France's grave financial and taxation woes.

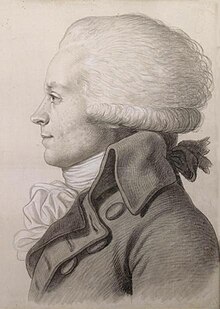

[34][56] Despite his commitment to democratic principles, Robespierre persistently donned knee-breeches and retained a meticulously groomed appearance with powdered, curled, and perfumed wig tied in a queue according to the old-fashioned style of the 18th century.

[87] A tactical purpose of this self-denying ordinance was to block the ambitions of the old leaders of the Jacobins, Antoine Barnave, Adrien Duport, and Alexandre de Lameth,[88] aspiring to create a constitutional monarchy roughly similar to that of England.

[103] Madame Roland named Pétion de Villeneuve, François Buzot and Robespierre as the three incorruptible patriots in an attempt to honour their purity of principles, their modest ways of living, and their refusal of bribes.

While arguing for the welfare of common soldiers, Robespierre urged new promotions to mitigate the domination of the officer class by the aristocratic and royalist École Militaire and the conservative National Guard.

[p] Along with other Jacobins, he urged the creation of an "armée révolutionnaire" in Paris, consisting of at least 20,000–23,000 men,[145][146] to defend the city, "liberty" (the revolution), maintain order and educate the members in democratic and republican principles, an idea he borrowed from Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

[174][175] On 16 August, Robespierre submitted a petition to the Legislative Assembly, endorsed by the Paris Commune urging the establishment of a provisional Revolutionary Tribunal specifically tasked with dealing with perceived "traitors" and "enemies of the people".

On Sunday morning 2 September the members of the Commune, gathering in the town hall to proceed the election of deputies to the National Convention, decided to maintain their seats and have Roland and Brissot arrested.

On 1 May 1793, according to the Girondin deputé Jacques-Antoine Dulaure [fr], 8,000 armed men surrounded the Convention and threatened not to leave if the emergency measures they demanded (a decent salary and maximum on food prices) were not adopted.

[250] On 8 and 12 May in the Jacobin Club, Robespierre restated the necessity of founding a revolutionary army that would search for grain, to be funded by a tax on the rich, and would be intended to defeat aristocrats and counter-revolutionaries.

[262] They declared themselves in a state of insurrection, dissolved the general council of the commune, and immediately reconstituted it, making it take a new oath; Francois Hanriot was elected as Commandant-Général of the Parisian National Guard.

In July, France teetered on the brink of civil war, besieged by aristocratic uprisings in Vendée and Brittany, by federalist revolts in Lyon, Le Midi, and Normandy, and confronted with hostility from across Europe and foreign factions.

[305] On 12 October, amid accusations by Hébert implicating Marie-Antoinette's engaging in incest with her son, Robespierre shared a meal with staunch supporters including Barère, Saint-Just, and Joachim Vilate.

[317] At the end of November, under intense emotional pressure from Lyonnaise women, who protested and gathered 10,000 signatures, Robespierre proposed the establishment of a secret commission to examine the cases of the Lyon rebels and investigate potential injustices.

[358] Following Robespierre's advice, a decree was accepted to present Saint-Just's account on Danton's alleged royalist tendencies at the tribunal, effectively ending further debates and restraining any further insults to justice by the accused.

On 22 April, Malesherbes, a lawyer who had defended the king and the deputés Isaac René Guy le Chapelier and Jacques Guillaume Thouret, four times elected president of the Constituent Assembly, were taken to the scaffold.

[372] The Tribunal transformed into a court of condemnation, denying suspects the right to counsel and offering only two verdicts: complete acquittal or death, often based more on jurors' moral convictions than evidence.

[375][376] On 11 July, shopkeepers, craftsmen, and others were temporarily released from prison due to overcrowding, with over 8,000 "suspects" initially confined by the start of Thermidor Year II (in the French Revolutionary calendar), according to François Furet.

In response, Robespierre asserted, "We should not compromise the interests humanity holds most dear, the sacred rights of a significant number of our fellow citizens," later exclaiming, "Perish the colonies, if it will cost you your happiness, your glory, your freedom.

[399][400] On the day following the emancipation decree, Robespierre addressed the Convention, lauding the French as pioneers to "summon all men to equality and liberty, and their full rights as citizens".

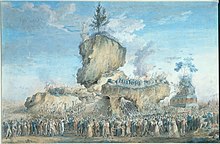

The following day, he delivered a detailed presentation to the Convention on religious and moral principles intertwined with republican ideals, introducing festivals dedicated to the Supreme Being and other virtues.

They decided that Hanriot, his aides-de-camp, Lavalette and Boulanger [fr],[456] the public prosecutor Dumas, the family Duplay and the printer Charles-Léopold Nicolas had to be arrested first, so Robespierre would be without support.

At approximately 6 p.m., the condemned were conveyed in three carts to the Place de la Révolution for execution, alongside Nicolas Francois Vivier, the final president of the Jacobins, and Antoine Simon, the cobbler who served as the jailer of the Dauphin.

According to Charles Barbaroux, who visited him early August 1792, his pretty boudoir was full of images of himself in every form and art; a painting, a drawing, a bust, a relief and six physionotraces on the tables.

Regarding dechristianization, he saw it as a gratuitous affront to the genuine religious needs of the people, especially outside Paris, and would only drive them into the arms of the refractory clergy, which is exactly what happened with disastrous results in the Vendée.

These illnesses not only explain Robespierre's repeated absences from committees and from the Convention during important periods, especially in 1794 when the Great Terror occurred but also the fact that his faculty of judgment deteriorated – as did his moods.

He argues, "Jacobin ideology and culture under Robespierre was an obsessive Rousseauiste moral Puritanism steeped in authoritarianism, anti-intellectualism, and xenophobia, and it repudiated free expression, basic human rights, and democracy.

"[557][558] He refers to the Girondin deputies Thomas Paine, Condorcet, Daunou, Cloots, Destutt and Abbé Gregoire denouncing Robespierre's ruthlessness, hypocrisy, dishonesty, lust for power, and intellectual mediocrity.