McMahon Line

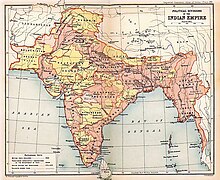

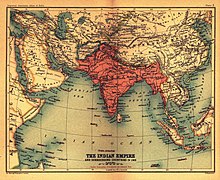

The McMahon Line is the boundary[1] between Tibet and British India as agreed in the maps and notes exchanged by the respective plenipotentiaries on 24–25 March 1914 at Delhi,[2] as part of the 1914 Simla Convention.

The line delimited the respective spheres of influence of the two countries in the eastern Himalayan region along northeast India and northern Burma (Myanmar), which were earlier undefined.

[14] It spans 890 kilometres (550 miles) from the corner of Bhutan to the Isu Razi Pass on the Burma border, largely along the crest of the Himalayas.

[15][16] The outcomes of the Simla Conference remained ambiguous for several decades because China did not sign the overall Convention but the British were hopeful of persuading the Chinese.

[17] It was revived in 1935 by Olaf Caroe, then deputy foreign secretary of British India, who obtained London's permission to implement it as well as to publish a revised version of Aitchison's 1928 Treaties.

China rejects the Simla Convention and the McMahon Line, contending that Tibet was not a sovereign state and therefore did not have the power to conclude treaties.

In June 2008, he explicitly recognized for the first time that "Arunachal Pradesh was a part of India under the agreement signed by Tibetan and British representatives".

At the end of the war the Brahmaputra valley of Assam came under its control and over the next few decades British India extended its direct administration over the region in stages.

The thickly forested hill tracts surrounding the valley were inhabited by tribal people, who were not easily amenable to British administrative control.

[34][35][36] The higher administration of British India was initially reluctant to concede these demands,[28] but, by 1912, the Army General Staff had proposed drawing a boundary along the crest of Himalayas.

[37] The British appear to have been clear that they were only extending the political administration of their rule but not the geographical extent of India, which was taken to include the Assam Himalayan region.

[41][42] After Beijing repudiated Simla, the British and Tibetan delegates attached a note denying China any privileges under the agreement and signed it as a bilateral accord.

[44] The Anglo-Russian Convention was jointly renounced by Russia and Britain in 1921,[45][non-primary source needed] but the McMahon Line was forgotten until 1935, when interest was revived by civil service officer Olaf Caroe.

[44] In April 1938, a small British force led by Captain G. S. Lightfoot arrived in Tawang and informed the monastery that the district was now Indian territory.

In 1944, the North-East Frontier Agency (NEFT) established direct administrative control for the entire area it was assigned, although Tibet soon regained authority in Tawang.

Among these were listed "Sayul [Zayul] and Walong and in direction of Pemakoe, Lonag, Lopa, Mon, Bhutan, Sikkim, Darjeeling and others on this side of river Ganges".

Several months after the conference, Nehru ordered maps of India published that showed expansive Indian territorial claims as definite boundaries, notably in Aksai Chin.

[21] The failure of the 1959 Tibetan uprising and the 14th Dalai Lama's arrival in India in March led Indian parliamentarians to censure Nehru for not securing a commitment from China to respect the McMahon Line.

In August 1959, Chinese troops captured a new Indian military outpost at Longju on the Tsari Chu (the main tributary, from the north, of the Subansiri River in Arunachal Pradesh.)

In a letter to Nehru dated 24 October 1959, Zhou Enlai proposed that India and China each withdraw their forces 20 kilometres from the line of actual control (LAC).

[21] On 8 September 1962, a Chinese unit attacked an Indian post at Dhola in the Namka Chu valley immediately south of the Thag La Ridge, seven kilometres north of the McMahon Line according to the map on page 360 of Maxwell.

[citation needed] In 1984, India Intelligence Bureau personnel in the Tawang region set up an observation post in the Sumdorong Chu Valley just south of the highest hill crest, but three kilometres north of the McMahon Line (the straight-line portion extending east from Bhutan for 30 miles).

[61] The Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi visited China in 1988 and agreed to a joint working group on boundary issues which has made little apparent positive progress.

Although there have been frequent incidents where one state has charged the other with incursions, causing tense encounters along the McMahon Line following India's nuclear test in 1998 and continuing to the present, both sides generally attribute these to disagreements of less than a kilometre as to the exact location of the LAC.