Media ecology

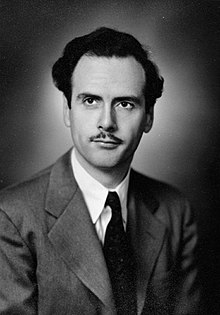

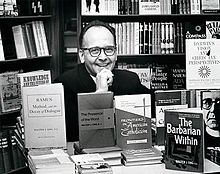

[1] The theoretical concepts were proposed by Marshall McLuhan in 1964,[2] while the term media ecology was first formally introduced by Neil Postman in 1968.

According to Postman, media ecology emphasizes the environments in which communication and technologies operate and spread information and the effects these have on the receivers.

[15] "Such information forms as the alphabet, the printed word, and television images are not mere instruments which make things easier for us.

Ecology in this context is used "because it is one of the most expressive [terms] language currently has to indicate the massive and dynamic interrelation of processes and objects, beings and things, patterns and matter".

Along with McLuhan (McLuhan 1962), Postman (Postman 1985) and Harold Innis, media ecology draws from many authors, including the work of Walter Ong, Lewis Mumford, Jacques Ellul, Félix Guattari, Eric Havelock, Susanne Langer, Erving Goffman, Edward T. Hall, George Herbert Mead, Margaret Mead, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Benjamin Lee Whorf, and Gregory Bateson.

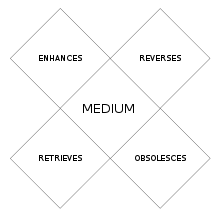

The effects of media - speech, writing, printing, photograph, radio or television – should be studied within the social and cultural spheres impacted by this technology.

This differs from the viewpoints of scholars such as Neil Postman, who argue that society should take a moral view of new media whether good or bad.

[31] McLuhan further notes that media introduced in the past brought gradual changes, which allowed people and society some time to adjust.

It started with a device created by Samuel Morse's invention of the telegraph and led to the telephone, the cell phone, television, internet, DVD, video games, etc.

[32] Robert K. Logan is professor emeritus of physics at the University of Toronto and Chief Scientist of the Strategic Innovation Lab at the Ontario College of Art and Design.

That's why McLuhan believed when a new medium appears, no matter what the concrete content it transmits, the new form of communication brings in itself a force that causes social transformation.

The key elements to media ecology have been largely attributed to Marshall McLuhan, who coined the statement "the medium is the message".

[37] McLuhan gave a center of gravity, a moral compass to media ecology which was later adapted and formally introduced by Neil Postman[37] The very foundation for this theory is based on a metaphor that provides a model for understanding the new territory, offers a vocabulary, and indicates in which directions to continue exploring.

This seems like a common sense idea today, where the internet makes it possible to check news stories around the globe, and social media connects individuals regardless of location.

Plugh says, "Where literate societies exchange an 'eye for an ear,' according to McLuhan, emphasizing the linear and sequential order of the world, electronic technology retrievers the total awareness of environment, characteristic of oral cultures, yet to an extended or 'global' level.

In his bestselling book, The Medium is the Message, he wrote, "there is absolutely no inevitability as long as there is a willingness to contemplate what is happening" (McLuhan & Fiore, 1967, p. 25).

[59][60][61] While advancing technologies allow for the study of media ecology, they also frequently disrupt the existing system of communication as they emerge.

Hildebrand points out that, "[e]nvironments are created and shaped by different media and modes and the physical, virtual, and mental processes and travels they generate".

[64] Similar to media ecology, mobilities research discusses a "flow" that shapes the environment, and creates contact zones.

Believing this to be true Eco says, "It is equally untrue that acting on the form and content of the message can convert the person receiving it."

[66] The North American variant of media ecology is viewed by numerous theorists such as John Fekete[56] and Neil Compton as meaningless or "McLuhanacy".

Compton wrote, "it would be better for McLuhan if his oversimplifications did not happen to coincide with the pretensions of young status-hungry advertising executives and producers, who eagerly provide him with a ready-made claque, exposure on the media, and a substantial income from addresses and conventions.

"[67] Additionally, As Lance Strate said: "Other critics complain that media ecology scholars like McLuhan, Havelock, and Ong put forth a "Great Divide" theory, exaggerating, for example, the difference between orality and literacy, or the alphabet and hieroglyphics.

He argues that a particular assemblage of software, hardware and sociality have brought about 'the widespread sense that there's something qualitatively different about today's Web.

This shift is characterised by co-creativity, participation and openness, represented by software that support for example, wiki-based ways of creating and accessing knowledge, social networking sites, blogging, tagging and 'mash ups'.

As new media power takes on new dimension in the digital realm, some scholars begin to focus on defending the democratic potentialities of the Internet on the perspective of corporate impermeability.

Today, corporate encroachment in cyberspace is changing the balance of power in the new media ecology, which "portends a new set of social relationships based on commercial exploitation".

[74] With "hundreds of cable channels and thousands of computer conferences, young generation might be able to isolate themselves within their own extremely opinionated forces".

[75] In 2009 a study was published by Cleora D'Arcy, Darin Eastburn and Bertram Bruce entitled "How Media Ecologies Can Address Diverse Student Needs".

She suggests that McLuhan's concepts are reflected in how transmedial storytelling helps audiences broaden their worldviews and accepted norms.