Medieval antisemitism

Even though it is not a part of Roman Catholic dogma, many Christians, including many members of the clergy, have held the Jewish people collectively responsible for the killing of Jesus, through the so-called blood curse of Pontius Pilate in the Gospels, among other things.

[1] As stated in the Boston College Guide to Passion Plays, "Over the course of time, Christians began to accept... that the Jewish people as a whole were responsible for killing Jesus.

According to this interpretation, both the Jews present at Jesus’ death and the Jewish people collectively and for all time, have committed the sin of deicide, or God-killing.

For 1900 years of Christian-Jewish history, the charge of deicide (which was originally attributed by Melito of Sardis) has led to hatred, violence against and murder of Jews in Europe and America.

"[3] This accusation was repudiated by the Catholic Church in 1964 under Pope Paul VI issued the document Nostra aetate as a part of Vatican II.

Local rulers and church officials closed many professions to the Jews, pushing them into marginal occupations considered socially inferior, such as tax and rent collecting and moneylending, tolerating them as a "necessary evil".

The Torah and later sections of the Hebrew Bible criticise usury but interpretations of the Biblical prohibition vary (the only time Jesus used violence was against money changers taking a toll to enter temple).

[5] Jews' role as moneylenders was later used against them, part of the justification in expelling them from England when they lacked the funds to continue lending the king money.

"(1406)[7] In one such case, a man named Agimet was ... coerced to say that Rabbi Peyret of Chambéry (near Geneva) had ordered him to poison the wells in Venice, Toulouse, and elsewhere.

The earliest papal bull on the subject, from Innocent IV in 1247, defended the Jews against claims of ritual murder and blood libel that had emerged in the Polish ecclesiastical authorities.

[13] For the next three years, Hinderbach continued to lobby jurists and scholars in Rome, and several prominent legal authorities issued rulings in support of both the prosecution's findings and the canonization of Simon.

[13] Perhaps due to this popular pressure, Pope Sixtus IV issued a papal bull that declared the trial legal, but did not officially recognize the Jews' guilt, thereby closing off the possibility of Simon's martyrdom.

The number of Jews permitted to reside in different places was limited; they were concentrated in ghettos[17] and were not allowed to own land; they were subject to discriminatory taxes on entering cities or districts other than their own, were forced to swear special Jewish Oaths, and suffered a variety of other measures, including restrictions on dress.

In 1209, stripped to the waist and barefoot, Raymond VI was obliged to swear that he would no longer allow Jews to hold public office.

In 1229 his son Raymond VII, underwent a similar ceremony where he was obliged to prohibit the public employment of Jews, this time at Notre Dame in Paris.

By the next generation a new, zealously Catholic, ruler was arresting and imprisoning Jews for no crime, raiding their houses, seizing their cash, and removing their religious books.

A historian has argued that organised and official persecution of the Jews became a normal feature of life in southern France only after the Albigensian Crusade because it was only then that the Church became powerful enough to insist that measures of discrimination be applied.

[19] In the Middle Ages in Europe persecutions and formal expulsions of Jews were liable to occur at intervals, although it should be said that this was also the case for other minority communities, whether religious or ethnic.

[22] The practice of expelling the Jews accompanied by confiscation of their property, followed by temporary readmissions for ransom, was utilized to enrich the French crown during 12th-14th centuries.

Already restricted to a limited number of occupations, the Jews saw Edward abolish their "privilege" to lend money, choke their movements and activities and were forced to wear a yellow patch.

When those who chose expulsion arrived at the port in Lisbon, they were met by clerics and soldiers who used force, coercion, and promises in order to baptize them and prevent them from leaving the country.

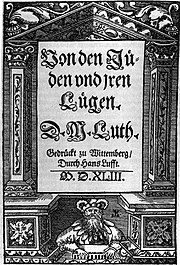

Luther's writings instead instigated another wave of political expulsions of Jewish populations from German localities, in the years immediately succeeding the release of “On the Jews and Their Lies” and for a few decades after the fact.

[23] According to Paul Johnson, Luther's book "may be termed the first work of modern anti-Semitism, and a giant step forward on the road to the Holocaust.

"[24] In his final sermon shortly before his death, however, Luther preached "We want to treat them with Christian love and to pray for them, so that they might become converted and would receive the Lord.

Some of this art was based on preconceived notions about how Jews dressed or looked, as well as the “sinning” acts which Christians believed that they committed.

As with much other medieval art of the Jews,[28] many of the 13 are depicted as in some way being complicit or directly aiding the Crucifixion of Christ, furthering the charge of Jewish deicide.

With that in mind, however, some scholars argue that Naumberg's reliefs are unusually not anti-Jewish for their time period in their portrayal of the Jews, as not all of them are sculpted as unambiguously evil or malicious.

Their haggardly, poor appearance is contrasted with the non-Jews of the image, including Roman guards, who are presented with a degree of fashion and status through their capes and typical tunics and similar attire.

[citation needed] Further, according to Medieval Christians, anyone who did not agree with their ideas of faith, including the Jewish people, were automatically assumed to be friendly with the devil and simultaneously condemned to hell.