Cavalieri's principle

In geometry, Cavalieri's principle, a modern implementation of the method of indivisibles, named after Bonaventura Cavalieri, is as follows:[1] Today Cavalieri's principle is seen as an early step towards integral calculus, and while it is used in some forms, such as its generalization in Fubini's theorem and layer cake representation, results using Cavalieri's principle can often be shown more directly via integration.

In the other direction, Cavalieri's principle grew out of the ancient Greek method of exhaustion, which used limits but did not use infinitesimals.

Cavalieri's principle was originally called the method of indivisibles, the name it was known by in Renaissance Europe.

[2] Cavalieri developed a complete theory of indivisibles, elaborated in his Geometria indivisibilibus continuorum nova quadam ratione promota (Geometry, advanced in a new way by the indivisibles of the continua, 1635) and his Exercitationes geometricae sex (Six geometrical exercises, 1647).

[3] While Cavalieri's work established the principle, in his publications he denied that the continuum was composed of indivisibles in an effort to avoid the associated paradoxes and religious controversies, and he did not use it to find previously unknown results.

[4] In the 3rd century BC, Archimedes, using a method resembling Cavalieri's principle,[5] was able to find the volume of a sphere given the volumes of a cone and cylinder in his work The Method of Mechanical Theorems.

In the 5th century AD, Zu Chongzhi and his son Zu Gengzhi established a similar method to find a sphere's volume.

The transition from Cavalieri's indivisibles to Evangelista Torricelli's and John Wallis's infinitesimals was a major advance in the history of calculus.

The indivisibles were entities of codimension 1, so that a plane figure was thought as made out of an infinite number of 1-dimensional lines.

Meanwhile, infinitesimals were entities of the same dimension as the figure they make up; thus, a plane figure would be made out of "parallelograms" of infinitesimal width.

Applying the formula for the sum of an arithmetic progression, Wallis computed the area of a triangle by partitioning it into infinitesimal parallelograms of width 1/∞.

N. Reed has shown[6] how to find the area bounded by a cycloid by using Cavalieri's principle.

The two points tracing the cycloids are therefore at equal heights.

By Cavalieri's principle, the circle therefore has the same area as that region.

Consider the rectangle bounding a single cycloid arch.

The new rectangle, of area twice that of the circle, consists of the "lens" region between two cycloids, whose area was calculated above to be the same as that of the circle, and the two regions that formed the region above the cycloid arch in the original rectangle.

One may initially establish it in a single case by partitioning the interior of a triangular prism into three pyramidal components of equal volumes.

One may show the equality of those three volumes by means of Cavalieri's principle.

In fact, Cavalieri's principle or similar infinitesimal argument is necessary to compute the volume of cones and even pyramids, which is essentially the content of Hilbert's third problem – polyhedral pyramids and cones cannot be cut and rearranged into a standard shape, and instead must be compared by infinite (infinitesimal) means.

The ancient Greeks used various precursor techniques such as Archimedes's mechanical arguments or method of exhaustion to compute these volumes.

, with equal dimensions but with its apex and base flipped.

of the flipped paraboloid is equal to the ring-shaped cross-sectional area

, then one can use Cavalieri's principle to derive the fact that the volume of a sphere is

units above the "equator" intersects the sphere in a circle of radius

The area of the plane's intersection with the part of the cylinder that is outside of the cone is also

As can be seen, the area of the circle defined by the intersection with the sphere of a horizontal plane located at any height

equals the area of the intersection of that plane with the part of the cylinder that is "outside" of the cone; thus, applying Cavalieri's principle, it could be said that the volume of the half sphere equals the volume of the part of the cylinder that is "outside" the cone.

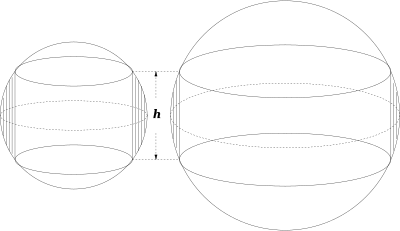

In what is called the napkin ring problem, one shows by Cavalieri's principle that when a hole is drilled straight through the centre of a sphere where the remaining band has height

, the volume of the remaining material surprisingly does not depend on the size of the sphere.

cancels; hence the lack of dependence of the bottom-line answer upon