Microplasma

[1] Further research by David Staack provided a graph of ideal electrode distances, voltages, and carrier gases tested for microplasma generation.

Successful experiments have used Ti:Sm, KrF, and YAG lasers, which can be applied to a variety of substrates such as lithium, germanium, plastics, and glass.

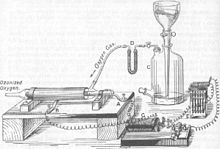

[4][5] In 1857, Werner von Siemens, a German scientist, originated ozone generation using a dielectric barrier discharge apparatus for biological decontamination.

In February 2003, Kunihide Tachibana, a professor of Kyoto University held the first international workshop on microplasmas (IWM) in Hyogo, Japan.

In the plasma display panels, X and Y grid of electrodes, separated by a MgO dielectric layer and surrounded by a mixture of inert gases - such as argon, neon or xenon, the individual picture elements are addressed.

Once energized, the plasma cells release ultraviolet (UV) light which then strikes and excites red, green and blue phosphors along the face of each pixel, causing them to glow.

Unlike fluorescent lamps, which require the electrodes to be far apart in a cylindrical cavity and vacuum conditions, microplasma light sources can be put into many different shapes and configurations, and generate heat.

This is opposed to the more commonly used fluorescent lamps which require a noble gas atmosphere (usually argon), where excimer formation and resulting radiative decomposition strikes a phosphor coating to create light.

For example, capillary plasma electrode (CPE) discharge was used to effectively destroy volatile organic compounds such as benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, xylene, ethylene, heptane, octane, and ammonia in the surrounding air for use in advanced life support systems designed for enclosed environments.

The small size and modest power required for microplasma devices employ a variety of environmental sensing applications and detect trace concentrations of hazardous species.

Herring and his colleagues at Caviton Inc. have simulated this system by coupling a microplasma device with a commercial gas chromatography column (GC).

The microplasma device is situated at the exit of the GC column, which records the relative fluorescence intensity of specific atomic and molecular dissociation fragments.

For the detection of less complex species, the temporal sorting done by the GC column is not necessary since the direct observation of fluorescence produced in the microplasma is sufficient.

Becker and his co-workers used a single flow-through dc-excited microplasma reactor to generate hydrogen from an atmospheric pressure mixture of ammonia and argon for use in small, portable fuel cells.

[9][10] Although through modeling the reforming reaction it was found that the amount of input electrical power to chemical conversion could increase by improving the device as well as the system parameters.

An article by Klages et al. describes the addition of amino groups to the surfaces of polymers after treatment with a pulsed DC discharge apparatus using nitrogen containing gases.

It was found that ammonia gas microplasmas add on an average of 2.4 amino groups per square nanometer of a nitrocellulose membrane, and increase the strength at which the layers of the substrate can bind.

His research team has found that by applying a microplasma jet to an electrolytic solution which has either a gold or silver anode is submerged produces the relevant cations.

The plasma skin regeneration (PSR) device consists of an ultra–high-radiofrequency generator that excites a tuned resonator and imparts energy to a flow of inert nitrogen gas within the handpiece.

Nitrogen is used as the gaseous source because it is able to purge oxygen from the surface of the skin, minimizing the risk of unpredictable hot spots, charring, and scar formation.

Repeated low-energy PSR treatment is an effective modality for improving dyspigmentation, smoothness, and skin laxity associated with photoaging.

Active research into microplasma sputtering for conductive interconnect thin film deposition poses a potential additive manufacturing alternative to costly semiconductor industry production standards.

Additionally, atmospheric conditions permitted by this method eliminate the substantial cost barrier presented by the necessity for the expensive, complex vacuum systems in which contemporary sputtering operations are performed.

Given the method’s relatively low cost and its broad versatility, attaining production quality on par with modern industry standards could potentially stand to spur a revolution in mass-customizable electronics.

However, the centers’ study confirms that biofilms cultivated in the root canal of extracted human teeth can be easily destroyed by the application of microplasma.

Lee and his colleagues experimented with this method, examining how microplasma along with hydrogen peroxide effects blood stained human teeth.

Microplasma that is sustained near room temperature can destroy bacteria, viruses, and fungi deposited on the surfaces of surgical instruments and medical devices.

Jean Michel Pouvesle has been working at the University of Orléans in France, in the Group for Research and Studies on Mediators of Inflammation (GREMI), experimenting with the effects of microplasma on cancer cells.

Pouvesle along with other scientists has created a dielectric barrier discharge and plasma gun for cancer treatment, in which microplasma will be applied to both in vitro and in vivo experiments.

This application will reveal the role of ROS (Reactive Oxygen Species), DNA damage, cell cycle modification, and apoptosis induction.