Middle Chinese

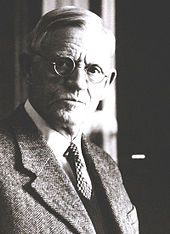

The Swedish linguist Bernhard Karlgren believed that the dictionary recorded a speech standard of the capital Chang'an of the Sui and Tang dynasties.

The reconstruction of Middle Chinese phonology is largely dependent upon detailed descriptions in a few original sources.

[5] The Qieyun is thus the oldest surviving rhyme dictionary and the main source for the pronunciation of characters in Early Middle Chinese (EMC).

At the time of Bernhard Karlgren's seminal work on Middle Chinese in the early 20th century, only fragments of the Qieyun were known, and scholars relied on the Guangyun (1008), a much expanded edition from the Song dynasty.

However, significant sections of a version of the Qieyun itself were subsequently discovered in the caves of Dunhuang, and a complete copy of Wang Renxu's 706 edition from the Palace Library was found in 1947.

The categories of initials and finals actually represented were first identified by the Cantonese scholar Chen Li in a careful analysis published in his Qieyun kao (1842).

[10] A single rhyme class may contain multiple finals, generally differing only in the medial (especially when it is /w/) or in so-called chongniu doublets.

[11][12] The Yunjing (c. 1150 AD) is the oldest of the so-called rime tables, which provide a more detailed phonological analysis of the system contained in the Qieyun.

They were aware of this, and attempted to reconstruct Qieyun phonology as well as possible through a close analysis of regularities in the system and co-occurrence relationships between the initials and finals indicated by the fanqie characters.

[14] Other scholars do not view them not as phonetic categories, but instead as formal devices exploiting distributional patterns in the Qieyun to achieve a compact presentation.

[19] For example, the following table shows the pronunciation of the numerals in three modern Chinese varieties, as well as borrowed forms in Vietnamese, Korean and Japanese: Although the evidence from Chinese transcriptions of foreign words is much more limited, and is similarly obscured by the mapping of foreign pronunciations onto Chinese phonology, it serves as direct evidence of a sort that is lacking in all the other types of data, since the pronunciation of the foreign languages borrowed from—especially Sanskrit and Gandhari—is known in great detail.

[24] At the end of the 19th century, European students of Chinese sought to solve this problem by applying the methods of historical linguistics that had been used in reconstructing Proto-Indo-European.

Volpicelli (1896) and Schaank (1897) compared the rime tables at the front of the Kangxi Dictionary with modern pronunciations in several varieties, but had little knowledge of linguistics.

[25] Bernhard Karlgren, trained in transcription of Swedish dialects, carried out the first systematic survey of modern varieties of Chinese.

[26] Unaware of Chen Li's study, he repeated the analysis of the fanqie required to identify the initials and finals of the dictionary.

He believed that the resulting categories reflected the speech standard of the capital Chang'an of the Sui and Tang dynasties.

He interpreted the many distinctions as a narrow transcription of the precise sounds of this language, which he sought to reconstruct by treating the Sino-Xenic and modern dialect pronunciations as reflexes of the Qieyun categories.

A small number of Qieyun categories were not distinguished in any of the surviving pronunciations, and Karlgren assigned them identical reconstructions.

[28] Hugh M. Stimson used a simplified version of Martin's system as an approximate indication of the pronunciation of Tang poetry.

[6] Several scholars have compared the Qieyun system to cross-dialectal descriptions of English pronunciations, such as John C. Wells's lexical sets, or the notation used in some dictionaries.

To remedy this, William H. Baxter produced his own notation for the Qieyun and rime table categories for use in his reconstruction of Old Chinese.

They argue for a full application of the comparative method to the modern varieties, supplemented by systematic use of transcription data.

The most widely used transcriptions are Li Fang-Kuei's modification of Karlgren's reconstruction and William Baxter's typeable notation.

In contrast, identifying the initials of the Qieyun required a painstaking analysis of fanqie relationships across the whole dictionary, a task first undertaken by the Cantonese scholar Chen Li in 1842 and refined by others since.

Moreover, most scholars believe that some distinctions among the 36 initials were no longer current at the time of the rime tables, but were retained under the influence of the earlier dictionaries.

[76] In 1954, André-Georges Haudricourt showed that Vietnamese counterparts of the rising and departing tones corresponded to final /ʔ/ and /s/, respectively, in other (atonal) Austroasiatic languages.

He thus argued that the Austroasiatic proto-language had been atonal, and that the development of tones in Vietnamese had been conditioned by these consonants, which had subsequently disappeared, a process now known as tonogenesis.

[77] Around the end of the first millennium AD, Middle Chinese and the southeast Asian languages experienced a phonemic split of their tone categories.

Cantonese maintains these tones and has developed an additional distinction in checked syllables, resulting in a total of nine tonal categories.

There was a well-developed system of derivational and possibly inflectional morphology, formed using consonants added onto the beginning or end of a syllable.