Tamil language

Tamil was the lingua franca for early maritime traders, with inscriptions found in places like Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Egypt.

[17][18] The Hathigumpha inscription, inscribed around a similar time period (150 BCE), by Kharavela, the Jain king of Kalinga, also refers to a Tamira Samghatta (Tamil confederacy)[19] The Samavayanga Sutra dated to the 3rd century BCE contains a reference to a Tamil script named 'Damili'.

Alternatively, he suggests a derivation of tamiḻ < tam-iḻ < *tav-iḻ < *tak-iḻ, meaning in origin "the proper process (of speaking)".

[22] However, this is deemed unlikely by Southworth due to the contemporary use of the compound 'centamiḻ', which means refined speech in the earliest literature.

The material evidence suggests that the speakers of Proto-Dravidian were of the culture associated with the Neolithic complexes of South India,[37] but it has also been related to the Harappan civilization.

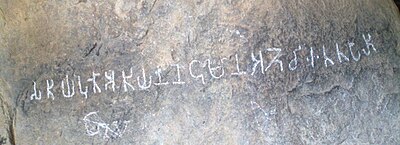

[43] Tamil language inscriptions written in Brahmi script have been discovered in Sri Lanka and on trade goods in Thailand and Egypt.

[44][45] In November 2007, an excavation at Quseir-al-Qadim revealed Egyptian pottery dating back to first century BCE with ancient Tamil Brahmi inscriptions.

[44] There are a number of apparent Tamil loanwords in Biblical Hebrew dating to before 500 BCE, the oldest attestation of the language.

The language is spoken among small minority groups in other states of India which include Karnataka, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Delhi, Andaman and Nicobar Islands in India and in certain regions of Sri Lanka such as Colombo and the hill country.

Tamil or dialects of it were used widely in the state of Kerala as the major language of administration, literature and common usage until the 12th century CE.

Tamil was also used widely in inscriptions found in southern Andhra Pradesh districts of Chittoor and Nellore until the 12th century CE.

[64] There are currently sizeable Tamil-speaking populations descended from colonial-era migrants in Malaysia, Singapore, Philippines, Mauritius, South Africa, Indonesia,[65] Thailand,[66] Burma, and Vietnam.

[72] Many in Réunion, Guyana, Fiji, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago have Tamil origins,[73] but only a small number speak the language.

[82][83] Tamil enjoys a special status of protection under Article 6(b), Chapter 1 of the Constitution of South Africa and is taught as a subject in schools in KwaZulu-Natal province.

The recognition was announced by the contemporaneous President of India, Abdul Kalam, who was a Tamilian himself, in a joint sitting of both houses of the Indian Parliament on 6 June 2004.

For example, it is possible to write centamiḻ with a vocabulary drawn from caṅkattamiḻ, or to use forms associated with one of the other variants while speaking koṭuntamiḻ.

Most contemporary cinema, theatre and popular entertainment on television and radio, for example, is in koṭuntamiḻ, and many politicians use it to bring themselves closer to their audience.

The traditional system prescribed by classical grammars for writing loan-words, which involves respelling them in accordance with Tamil phonology, remains, but is not always consistently applied.

It uses diacritics to map the much larger set of Brahmic consonants and vowels to Latin script, and thus the alphabets of various languages, including English.

Tamil employs agglutinative grammar, where suffixes are used to mark noun class, number, and case, verb tense and other grammatical categories.

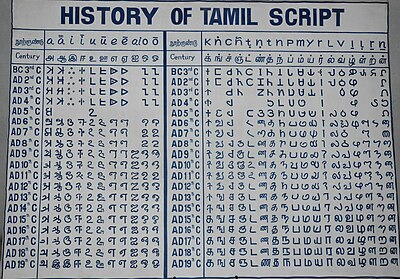

Modern Tamil writing is largely based on the 13th-century grammar Naṉṉūl which restated and clarified the rules of the Tolkāppiyam, with some modifications.

Traditional Tamil grammar consists of five parts, namely eḻuttu, col, poruḷ, yāppu, aṇi.

To give an example, the word pōkamuṭiyātavarkaḷukkāka (போகமுடியாதவர்களுக்காக) means "for the sake of those who cannot go" and consists of the following morphemes: போகpōkagoமுடிmuṭiaccomplishஆத்ātNEG.IMPRSஅaPTCPவர்varNMLZகள்kaḷPLஉக்குukkutoஆகākaforபோக முடி ஆத் அ வர் கள் உக்கு ஆகpōka muṭi āt a var kaḷ ukku ākago accomplish NEG.IMPRS PTCP NMLZ PL to forTamil nouns (and pronouns) are classified into two super-classes (tiṇai)—the "rational" (uyartiṇai), and the "irrational" (akṟiṇai)—which include a total of five classes (pāl, which literally means "gender").

For example, a sentence may only have a verb—such as muṭintuviṭṭatu ("completed")—or only a subject and object, without a verb such as atu eṉ vīṭu ("That [is] my house").

[116] Nonetheless, a number of words used in classical and modern Tamil are loanwords from the languages of neighbouring groups, or with whom the Tamils had trading links, including Malay (e.g. cavvarici "sago" from Malay sāgu), Chinese (for example, campān "skiff" from Chinese san-pan) and Greek (for example, ora from Greek ὥρα).

[123][124][125] In addition, Sanskritisation was actively resisted by a number of authors of the late medieval period,[126] culminating in the 20th century in a movement called taṉit tamiḻ iyakkam (meaning "pure Tamil movement"), led by Parithimaar Kalaignar and Maraimalai Adigal, which sought to remove the accumulated influence of Sanskrit on Tamil.

[127] As a result of this, Tamil in formal documents, literature and public speeches has seen a marked decline in the use Sanskrit loan words in the past few decades,[128] under some estimates having fallen from 40 to 50% to about 20%.

[62] As a result, the Prakrit and Sanskrit loan words used in modern Tamil are, unlike in some other Dravidian languages, restricted mainly to some spiritual terminology and abstract nouns.

[131] Examples in English include cheroot (curuṭṭu meaning 'rolled up'),[132] mango (from māṅgāy),[132] mulligatawny (from miḷaku taṇṇīr 'pepper water'), pariah (from paṟaiyar), curry (from kaṟi),[133] catamaran (from kaṭṭu maram 'bundled logs'),[132] and congee (from kañji 'rice porridge' or 'gruel').

They among-one-another brotherly feeling share-in act must.Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.