Second moment of area

In both cases, it is calculated with a multiple integral over the object in question.

Its unit of dimension, when working with the International System of Units, is meters to the fourth power, m4, or inches to the fourth power, in4, when working in the Imperial System of Units or the US customary system.

In order to maximize the second moment of area, a large fraction of the cross-sectional area of an I-beam is located at the maximum possible distance from the centroid of the I-beam's cross-section.

The planar second moment of area provides insight into a beam's resistance to bending due to an applied moment, force, or distributed load perpendicular to its neutral axis, as a function of its shape.

The polar second moment of area provides insight into a beam's resistance to torsional deflection, due to an applied moment parallel to its cross-section, as a function of its shape.

with respect to some reference plane), or the polar second moment of area (

In each case the integral is over all the infinitesimal elements of area, dA, in some two-dimensional cross-section.

, where r is the distance to some potential rotation axis, and the integral is over all the infinitesimal elements of mass, dm, in a three-dimensional space occupied by an object Q.

The MOI, in this sense, is the analog of mass for rotational problems.

where For example, when the desired reference axis is the x-axis, the second moment of area

The second moment of the area is crucial in Euler–Bernoulli theory of slender beams.

More generally, the product moment of area is defined as[3]

It is sometimes necessary to calculate the second moment of area of a shape with respect to an

However, it is often easier to derive the second moment of area with respect to its centroidal axis,

, and use the parallel axis theorem to derive the second moment of area with respect to the

For the simplicity of calculation, it is often desired to define the polar moment of area (with respect to a perpendicular axis) in terms of two area moments of inertia (both with respect to in-plane axes).

This relationship relies on the Pythagorean theorem which relates

The second moment of area for the entire shape is the sum of the second moment of areas of all of its parts about a common axis.

In other words, the second moment of area of "missing" parts are considered negative for the method of composite shapes.

represents the second moment of area with respect to the x-axis;

represents the second moment of area with respect to the y-axis;

represents the polar moment of inertia with respect to the z-axis.

Consider an annulus whose center is at the origin, outside radius is

Because of the symmetry of the annulus, the centroid also lies at the origin.

minus the polar moment of inertia of a circle with radius

First, let us derive the polar moment of inertia of a circle with radius

Instead of obtaining the second moment of area from Cartesian coordinates as done in the previous section, we shall calculate

axis for an annulus is simply, as stated above, the difference of the second moments of area of a circle with radius

integral the first time around to reflect the fact that there is a hole.

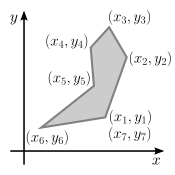

The second moment of area about the origin for any simple polygon on the XY-plane can be computed in general by summing contributions from each segment of the polygon after dividing the area into a set of triangles.