Monarchy

The political legitimacy of the inherited, elected or proclaimed monarchy has most often been based on claims of representation of people and land through some form of relation (e.g. kinship) and divine right or other achieved status.

Some countries have preserved titles such as "kingdom" while dispensing with an official serving monarch (note the example of Francoist Spain from 1947 to 1975) or while relying on a long-term regency (as in the case of Hungary in the Horthy era from 1920 to 1944).

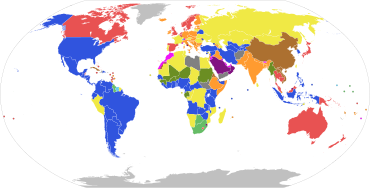

As of 2024[update], forty-three sovereign nations in the world have a monarch, including fifteen Commonwealth realms that share King Charles III as their head of state.

By the 17th century, monarchy was challenged by evolving parliamentarism e.g. through regional assemblies (such as the Icelandic Commonwealth, the Swiss Landsgemeinde and later Tagsatzung, and the High Medieval communal movement linked to the rise of medieval town privileges) and by modern anti-monarchism e.g. of the temporary overthrow of the English monarchy by the Parliament of England in 1649, the American Revolution of 1776 and the French Revolution of 1789.

As such republics have become the opposing and alternative form of government to monarchy,[10][11][12] despite some having seen infringements through lifelong or even hereditary heads of state, such as in North Korea.

Today forty-three sovereign nations in the world have a monarch, including fifteen Commonwealth realms that have Charles III as the head of state.

[14] In some nations, however, such as Morocco, Qatar, Liechtenstein, and Thailand, the hereditary monarch has more political influence than any other single source of authority in the state, even if it is by a constitutional mandate.

The prospect of retaining the ruler appeals to opposition groups who value both democracy and stability, but it also has implications for their ability to organize and sustain mass protest.

There are examples of joint sovereignty of spouses, parent and child or other relatives (such as William III and Mary II in the kingdoms of England and Scotland, Tsars Peter I and Ivan V of Russia, and Charles I and Joanna of Castile).

Many European monarchs have been styled Fidei defensor (Defender of the Faith); some hold official positions relating to the state religion or established church.

In the Western political tradition, a morally based, balanced monarchy was stressed as the ideal form of government, and little attention was paid to modern-day ideals of egalitarian democracy: e.g. Saint Thomas Aquinas unapologetically declared: "Tyranny is wont to occur not less but more frequently on the basis of polyarchy [rule by many, i.e. oligarchy or democracy] than on the basis of monarchy."

However, Thomas Aquinas also stated that the ideal monarchical system would also have at lower levels of government both an aristocracy and elements of democracy in order to create a balance of power.

In Dante Alighieri's De Monarchia, a spiritualised, imperial Catholic monarchy is strongly promoted according to a Ghibelline world-view in which the "royal religion of Melchizedek" is emphasised against the priestly claims of the rival papal ideology.

In Saudi Arabia, the king is a head of state who is both the absolute monarch of the country and the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques of Islam (خادم الحرمين الشريفين).

In the Muslim world, titles of monarchs include caliph (successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a leader of the entire Muslim community), padishah (emperor), sultan or sultana, shâhanshâh (emperor), shah, malik (king) or malikah (queen), emir (commander, prince) or emira (princess), sheikh or sheikha, imam (used in Oman).

In Botswana, South Africa, Ghana and Uganda, the ancient kingdoms and chiefdoms that were met by the colonialists when they first arrived on the continent are now constitutionally protected as regional or sectional entities.

Furthermore, in Nigeria, though the hundreds of sub-regional polities that exist there are not provided for in the current constitution, they are nevertheless legally recognised aspects of the structure of governance that operates in the nation.

For example, the Yoruba city-state of Akure in south-western Nigeria is something of an elective monarchy: its reigning Oba Deji has to be chosen by an electoral college of nobles from amongst a finite collection of royal princes of the realm upon the death or removal of an incumbent.

In a hereditary monarchy, the position of monarch is inherited according to a statutory or customary order of succession, usually within one royal family tracing its origin through a historical dynasty or bloodline.

In 1980, Sweden became the first monarchy to declare equal (full cognatic) primogeniture, meaning that the eldest child of the monarch, whether female or male, ascends to the throne.

On June 21, 2017, King Salman of Saudi Arabi revolted against this style of monarchy and elected his son to inherit the throne.

The Pope of the Roman Catholic Church (who rules as Sovereign of the Vatican City State) is elected for life by the College of Cardinals.

In the Sovereign Military Order of Malta, the Prince and Grand Master is elected for life tenure by the Council Complete of State from within its members.

Other ways to succeed to a monarchy can be through claiming alternative votes (e.g. as in the case of the Western Schism), claims of a mandate to rule (e.g. a popular or divine mandate), military occupation, a coup d'état, a will of the previous monarch or treaties between factions inside and outside of a monarchy (e.g. as in the case of the War of the Spanish Succession).

The legitimacy and authorities of monarchs are often proclaimed and recognized through occupying and being invested with insignia, seats, deeds and titles, like in the course of coronations.

In cases of succession challenges, it can be instrumental for pretenders to secure or install legitimacy through the above, for example proof of accession like insignia, through treaties or a claim of a divine mandate to rule (e.g. by Hong Xiuquan and his Taiping Heavenly Kingdom).

All fifteen realms are constitutional monarchies and full democracies where the King has limited powers or a largely ceremonial role.

Brunei Darussalam, Oman, and Saudi Arabia remain absolute monarchies; Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar and United Arab Emirates are classified as mixed, meaning there are representative bodies of some kind, but the monarch retains most of his powers.

Eswatini is unique among these monarchies, often being considered a diarchy: the King, or Ngwenyama, rules alongside his mother, the Ndlovukati, as dual heads of state.

At the time the constitution was adopted, it was anticipated that future heads of state would be chosen from among the four Tama a 'Aiga "royal" paramount chiefs.

Parliamentary systems : Head of government is elected or nominated by and accountable to the legislature

Presidential system : Head of government (president) is popularly elected and independent of the legislature

Hybrid systems:

Other systems:

Note: this chart represents the de jure systems of government, not the de facto degree of democracy.