Monkeys in Chinese culture

Jue)[1] Nao 夒 was the first "monkey" term recorded in the historical corpus of written Chinese, and frequently appeared in (14th–11th centuries BCE) Shang dynasty oracle bone inscriptions.

The poet Li Bai alludes to nao (猱) populating the Taihang Mountains, in the north of China, near the capital city Chang'an, in the poem "白馬篇": it should be duly noted that this literary source contextually suggests a temporal location of the West Han era.

[3] Yu 禺 "monkey" appeared on (11th–3rd centuries BCE) Zhou dynasty Chinese ritual bronzes as a pictograph showing a head, arms, and a tail.

The Bencao gangmu lists mihou synonyms of: muhou 沐猴, weihou 為猴, husun 胡孫, wangsun 王孫, maliu 馬留, and ju 狙; and Li Shizhen explains the names.

As macaque looks like a person from the Hu region (the north and west of China where non-Han ethnic groups lived in ancient times), it is called Husun [胡孫].

So it is colloquially called Maliu ([馬留] meaning "maintaining the horses") in the Hu region (the north and west of China where non-Han ethnic groups lived in ancient times).

[15] Qu Yuan's (c. 3rd-century) Chuci uses the term yuanyou 猿狖 three times (in Nine Pieces); for instance,[18] "Amid the deep woods there, in the twilight gloom, are the haunts where monkeys live."

[19] During the first centuries of our era, the binoms naoyuan or yuannao were superseded as words for "gibbon" by the single term yuan 猨, written with the classifier "quadruped" instead of that for "insect" 虫; and one prefers the phonetic 袁 to 爰 (rarely 員).

[22] In addition to meaning "golden snub-nosed monkey", Van Gulik notes that in modern Chinese zoological terminology, rong denotes the Callitrichidae (or Hapalidae) family including marmosets and tamarins.

[23] The Bencao gangmu entry for the rong 狨 explains the synonym nao 猱 signifies this monkey's rou 柔 "soft; supple" hair.

[40] The Tang dynasty chancellor Pei Yan wrote, The hu ["barbarians"] of the Western countries take its blood for dyeing their woolen rugs; its color is clean and will not turn black.

"[45] The Shuowen Jiezi writes feifei 𥝋𥝋 with an obsolete pictograph, and Xu Shen says: "People in the north call it Tulou [土螻 "earth cricket"].

Guo Pu's commentary gives the synonym menggui and says,[61] "An animal like a small [wei] proboscis monkey, purple black in color, from Yunnan (交趾 "Annam").

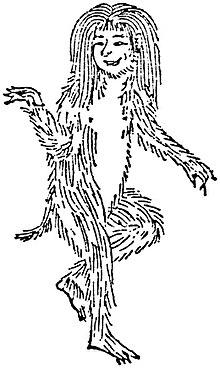

Japanese kakuen) as both a factual "large ape found in western mountains" and a mythological "single-sex species that abducts and mates with humans"; said to be either all males (viz.

The theory that [juefu], [xingxing], and [feifei] are the combined result of such observations is also supported by the fact that in the oldest pictures preserved, the human features prevail over the simian.

In the southern regions of China, many temples were built to the monkey-god who is worshipped as the Qitian dasheng 齊天大聖 "great saint equal to heaven", which was a name of Sun Wukong.

[65] The Soushenji (12)[66] "reported that in the southwest of Shu there were monkey-like animals whose names were [jiaguo 猳國], [mahua 馬化], or [jueyuan 玃猿, see "Jue and Juefu"].

De Groot describes them as either "a lewd fornicator of wives and maids" or "a seductress, in beautiful female forms, of adults and inexperienced youths, whose senses it bewitches at the detriment of their health".

The (c. 239 BCE) Lüshi Chunqiu has a "knack story" about the legendary archer Yang Youji 養由基 and a shen baiyuan "supernatural white gibbon" that instinctively knew the intentions of humans.

(20)[80] The Daoist discipline of daoyin "guide and pull" is based on the notion that circulating and absorbing qi "breath; life force" in the body can lead to longevity or even immortality.

Long-limbed animals were believed to be innately adept at absorbing qi and thus acquire "occult powers, including the ability to assume human shape, and to prolong their life to several hundred years".

Another animal associated with longevity was the he 鶴 "crane", whose long neck and legs supposedly enabled the bird to absorb qi and live up to a thousand years.

In the heart of a Himavat there was a large tree, which bore excellent fruits even bigger than the palmyra nuts having exceedingly sweet flavor; lovely hue and fragrance, which no man had ever seen or noticed before.

[88] For instance, the Tang poet Li Bai wrote poems about gibbons 白猿 in the Qiupu 秋浦 region (in south-central modern Anhui Province).

Zhou dynasty culture symbolically contrasted the gibbon as "gentleman; sage" (junzi 君子 or sheng 聖) and the macaque as "commoner; petty person" (xiaoren 小人).

The gibbon, on the contrary, inhabiting as it did the upper canopy of the primeval forest, rarely seen and extremely difficult to catch, was regarded as a denizen of the inscrutable, forbidding world of the high mountains and deep valleys, peopled by fairies and goblins.

[92] The earliest Chinese monkey-shaped objects,[93]: 1 believed to have been belt hooks, date from the late Eastern Zhou period (4th–3rd centuries BCE) and depict a gibbon with outstretched arms and hook-shaped hands.

Simians have played a role in traditional Chinese medicine, "which maintains that the meat, bones and livers of monkeys have various curative effects, ranging from detoxification to improving sex drive".

The meat of a xingxing 猩猩 monkey[37] supposedly "cures drowsiness and hunger, and desire for a cereal diet, it allows an exhausted man to travel well, and old age will not tell on him".

[95] Modern day official Chinese policy with regards to the procurement of certain monkeys for food makes their consumption illegal, with sentences of up to 10 years in prison for violators.