Multicellular organism

Multicellularity has evolved independently at least 25 times in eukaryotes,[7][8] and also in some prokaryotes, like cyanobacteria, myxobacteria, actinomycetes, Magnetoglobus multicellularis or Methanosarcina.

[19] Multicellular organisms, especially long-living animals, face the challenge of cancer, which occurs when cells fail to regulate their growth within the normal program of development.

However, Weismannist development is relatively rare (e.g., vertebrates, arthropods, Volvox), as a great part of species have the capacity for somatic embryogenesis (e.g., land plants, most algae, many invertebrates).

This is inexact, as living multicellular organisms such as animals and plants are more than 500 million years removed from their single-cell ancestors.

Modern phylogenetics uses sophisticated techniques such as alloenzymes, satellite DNA and other molecular markers to describe traits that are shared between distantly related lineages.

[citation needed] This kind of severely co-dependent symbiosis can be seen frequently, such as in the relationship between clown fish and Riterri sea anemones.

Although such symbiosis is theorized to have occurred (e.g., mitochondria and chloroplasts in animal and plant cells—endosymbiosis), it has happened only extremely rarely and, even then, the genomes of the endosymbionts have retained an element of distinction, separately replicating their DNA during mitosis of the host species.

Slime molds syncitia form from individual amoeboid cells, like syncitial tissues of some multicellular organisms, not the other way round.

To be deemed valid, this theory needs a demonstrable example and mechanism of generation of a multicellular organism from a pre-existing syncytium.

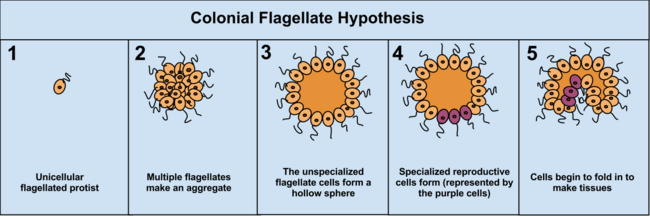

[36] The mechanism of this latter colony formation can be as simple as incomplete cytokinesis, though multicellularity is also typically considered to involve cellular differentiation.

Other examples of colonial organisation in protista are Volvocaceae, such as Eudorina and Volvox, the latter of which consists of up to 500–50,000 cells (depending on the species), only a fraction of which reproduce.

[41] Genes borrowed from viruses and mobile genetic elements (MGEs) have recently been identified as playing a crucial role in the differentiation of multicellular tissues and organs and even in sexual reproduction, in the fusion of egg cells and sperm.

[42][43] Such fused cells are also involved in metazoan membranes such as those that prevent chemicals from crossing the placenta and the brain body separation.

Felix Rey, of the Pasteur Institute in Paris, has constructed the 3D structure of the EFF-1 protein[46] and shown it does the work of linking one cell to another, in viral infections.

The fact that all known cell fusion molecules are viral in origin suggests that they have been vitally important to the inter-cellular communication systems that enabled multicellularity.

[47] This theory suggests that the oxygen available in the atmosphere of early Earth could have been the limiting factor for the emergence of multicellular life.

Mills[49] concludes that the amount of oxygen present during the Ediacaran is not necessary for complex life and therefore is unlikely to have been the driving factor for the origin of multicellularity.

Herron et al.[52] performed laboratory evolution experiments on the single-celled green alga, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, using paramecium as a predator.

[citation needed] It is impossible to know what happened when single cells evolved into multicellular organisms hundreds of millions of years ago.

[57] In the unicellular state, genes associated with reproduction and survival are expressed in a way that enhances the fitness of individual cells, but after the transition to multicellularity, the pattern of expression of these genes must have substantially changed so that individual cells become more specialized in their function relative to reproduction and survival.

As the transition progressed, cells that specialized tended to lose their own individuality and would no longer be able to both survive and reproduce outside the context of the group.