Nair

Their internal caste behaviours and systems are markedly different between the people in the northern and southern sections of the area, although there is not very much reliable information on those inhabiting the north.

Although the detail varied from one region to the next, the main points of interest to researchers of Nair marriage customs were the existence of two particular rituals—the pre-pubertal thalikettu kalyanam and the later sambandam—and the practice of polygamy in some areas.

Inscriptions on copper-plate regarding grants of land and rights to settlements of Jewish and Christian traders, dated approximately between the 7th- and 9th-centuries AD, refer to Nair chiefs and soldiers from the Eranad, Valluvanad, Venad (later known as Travancore) and Palghat areas.

Some early examples of these works being John Mandeville’s ‘’Travels’’ (1356), William Caxton’s ‘The mirrour of the wourld’ (1481), and Jean Boudin’s ‘Les sex livres de la republique’ (1576).

Up to this time the Nairs had been historically a military community, who along with the Nambudiri Brahmins owned most of the land in the region; after it, they turned increasingly to administrative service.

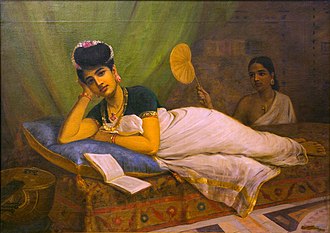

The low-hanging fabric was considered as specific to the Nair caste, and at the start of the 20th century it was noted that in more conservative rural areas a non-Nair could be beaten for daring to wear a cloth hanging low to the ground.

Wealthy Nairs might use silk for this purpose, and they also would cover their upper body with a piece of laced muslin; the remainder of the community used once to wear a material manufactured in Eraniyal but by the time of Panikkar's writing were generally using cotton cloth imported from Lancashire, England, and wore nothing above the waist.

This involved rubbing coconut oil onto the pregnant woman, followed by bathing, formal dressing, consultation with an astrologer regarding the expected date of birth and a ceremonial drinking of tamarind juice, dripped along the blade of a sword.

[77] In the months subsequent to the birth there followed other rituals, including those of purification and the adornment of the child with a symbolic belt to ward off illness, as well as a name-giving ceremony at which an astrologer again played a significant role.

In these instances, although they were obeisant to the rajah, they held a higher ritual rank than the Zamorin as a consequence of their longer history of government; they also had more power than the vassal chiefs.

[83] According to Gough, the villages were generally between one and four square miles in area and their lands were usually owned by one landlord family, who claimed a higher ritual rank than its other inhabitants.

[83] Nairs were not permitted to perform rites in the temples of the sanketams, the villages where the land was owned by a group of Nambudiri families, although they might have access to the outer courtyard area.

These analyses bear similarities to the Jatinirnayam, a Malayalam work that enumerated 18 main subgroups according to occupation, including drummers, traders, coppersmiths, palanquin bearers, servants, potters and barbers, as well as ranks such as the Kiriyam and Illam.

Except for high-ranking priests, the Nayar subdivisions mirror all the main caste categories: high-status aristocrats, military and landed; artisans and servants; and untouchables.

[95] The hypothesis, proposed by writers such as Fuller and Louis Dumont, that most of the subgroups were not subcastes, arises in large part because of the number of ways in which Nairs classified themselves, which far exceeded the 18 or so groups which had previously been broadly accepted.

These designations were, however, somewhat fluid: the numbers tended to rise and fall, dependent upon which source and which research was employed; it is likely also that the figures were skewed by Nairs claiming a higher status than they actually had, which was a common practice throughout India.

It has also been postulated that some exogamous families came together to form small divisions as a consequence of shared work experiences with, for example, a local Nambudiri or Nair chief.

Their claims illustrated that the desires and aspirations of self-promotion applied even at the very top of the community and this extended as far as each family refusing to admit that they had any peers in rank, although they would acknowledge those above and below them.

The membership of these two subgroups was statistically insignificant, being a small fraction of 1 per cent of the regional population, but the example of aspirational behaviour which they set filtered through to the significant ranks below them.

Most significantly, they adopted hypergamy and would utilise the rituals of thalikettu kalyanam and sambandham, which constituted their traditional version of a marriage ceremony, in order to advance themselves by association with higher-ranked participants and also to disassociate themselves from their existing rank and those below.

Nossiter has described its purpose at foundation as being "... to liberate the community from superstition, taboo and otiose custom, to establish a network of educational and welfare institutions, and to defend and advance Nair interests in the political arena.

"[39] Devika and Varghese believe the year of formation to be 1913 and argue that the perceived denial of 'the natural right' of upper castes to hold elected chairs in Travancore, a Hindu state, had pressured the founding of the NSS.

From its early years, when it was contending that the Nairs needed to join together if they were to become a political force, it argued that the caste members should cease referring to their traditional subdivisions and instead see themselves as a whole.

[85][116][125] The sambandham ceremony was simple compared to the thalikettu kalyanam, being marked by the gift of clothes (pudava) to the bride in front of some family members of both parties to the arrangement.

If the sambandham partner was a Brahmin man or the woman's father's sister's son (which was considered a proper marriage because it was outside the direct line of female descent) then the presentation was a low-key affair.

[116][125] The sambandham relationship was usually arranged by the karanavan but occasionally they would arise from a woman attracting a man in a temple, bathing pool or other public place.

[128] It has also been argued that the practice, along with judicious selection of the man who tied the thali, formed a part of the Nair aspirational culture whereby they would seek to improve their status within the caste.

[120]Although it is certain that in theory hypergamy can cause a shortage of marriageable women in the lowest ranks of a caste and promote upwards social movement from the lower Nair subdivisions, the numbers involved would have been very small.

Fuller believes that in the relatively undocumented southern Travancore monogamy may have been predominant, and that although the matrilineal joint family still applied it was usually the case that the wife lived with the tharavad of her husband.

The role of the Nair Service Society in successfully campaigning for continued changes in practices and legislation relating to marriage and inheritance also played its part.