Natural monopoly

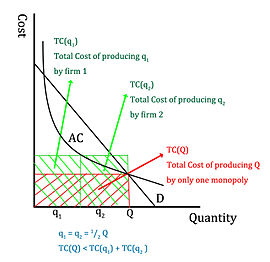

A natural monopoly is a monopoly in an industry in which high infrastructural costs and other barriers to entry relative to the size of the market give the largest supplier in an industry, often the first supplier in a market, an overwhelming advantage over potential competitors.

This frequently occurs in industries where capital costs predominate, creating large economies of scale about the size of the market; examples include public utilities such as water services, electricity, telecommunications, mail, etc.

[1] Natural monopolies were recognized as potential sources of market failure as early as the 19th century; John Stuart Mill advocated government regulation to make them serve the public good.

In an industry where a natural monopoly does not exist, the vast majority of industries, the marginal cost decreases with economies of scale, then increases as the company has growing pains (overworking its employees, bureaucracy, inefficiencies, etc.).

The reason is that the actual product of the enterprise as it continues to expand, the original fixed costs are gradually diluted.

Natural monopolies arise where the largest supplier in an industry, often the first supplier in a market, has an overwhelming cost advantage over other actual or potential competitors; this tends to be the case in industries where fixed costs predominate, creating economies of scale that are large in relation to the size of the market, as is the case in water and electricity services.

The fixed cost of constructing a competing transmission network is so high, and the marginal cost of transmission for the incumbent so low, that it effectively bars potential competitors from the monopolist's market, acting as a nearly insurmountable barrier to entry into the market place.

A firm with high fixed costs requires a large number of customers in order to have a meaningful return on investment.

In real life, companies produce or provide single goods and services but often diversify their operations.

Therefore, well-known American economists Samuelson and Nordhaus pointed out that economies of scope can also produce natural monopolies.

Baumol also noted that for a firm producing a single product, scale economies were a sufficient condition but not a necessary condition to prove subadditivity, the argument can be illustrated as follows: Proposition: Strict economies of scale are sufficient but not necessary for ray average cost to be strictly declining.

Combining all propositions gives: Proposition: Global scale economies are sufficient but not necessary for (strict) ray subadditivity, the condition for natural monopoly in the production of a single product or in any bundle of outputs produced in fixed proportions.

The development of the concept of natural monopoly is often attributed to John Stuart Mill, who (writing before the marginalist revolution) believed that prices would reflect the costs of production in absence of an artificial or natural monopoly.

Taking up the examples of professionals such as jewellers, physicians and lawyers, he said,[6] The superiority of reward is not here the consequence of competition, but of its absence: not a compensation for disadvantages inherent in the employment, but an extra advantage; a kind of monopoly price, the effect not of a legal, but of what has been termed a natural monopoly... independently of... artificial monopolies [i.e. grants by government], there is a natural monopoly in favour of skilled labourers against the unskilled, which makes the difference of reward exceed, sometimes in a manifold proportion, what is sufficient merely to equalize their advantages.

In contrast, common contemporary usage refers solely to market failure in a particular type of industry such as rail, post or electricity.

If a business can only be advantageously carried on by a large capital, this in most countries limits so narrowly the class of persons who can enter into the employment, that they are enabled to keep their rate of profit above the general level.

A trade may also, from the nature of the case, be confined to so few hands, that profits may admit of being kept up by a combination among the dealers.

It is well known that even among so numerous a body as the London booksellers, this sort of combination long continued to exist.

[8] Furthermore, Mill referred to network industries, such as electricity and water supply, roads, rail and canals, as "practical monopolies", where "it is the part of the government, either to subject the business to reasonable conditions for the general advantage or to retain such power over it, that the profits of the monopoly may at least be obtained for the public.

Whereby the rates are not left to the market but are regulated by the government; maximising profits, and subsequently societal reinvestment.

Government regulation may also come about at the request of a business hoping to enter a market otherwise dominated by a natural monopoly.

Common arguments in favour of regulation include the desire to limit a company's potentially abusive[12] or unfair market power, facilitate competition, promote investment or system expansion, or stabilise markets.

This is especially true in the case of essential utilities like electricity where a monopoly creates a captive market for a product few can refuse.

In general, though, regulation occurs when the government believes that the operator, left to his own devices, would behave in a way that is contrary to the public interest.

[13] In some countries an early solution to this perceived problem was government provision of, for example, a utility service.

Enabling a monopolistic company with the ability to change prices without regulation can have devastating effects in society.

A wave of nationalisation across Europe after World War II created state-owned companies in each of these areas, many of which operate internationally bidding on utility contracts in other countries.

[15] In recent years, bodies of information have observed the correlation between utility subsidies and welfare improvements.

[16] Today, across the world, public utilities are widely used to provide state-run water, electricity, gas, telecommunications, mass-transportation and postal services.

For instance, the web's open-source architecture has both stimulated massive growth and avoided a single company controlling the entire market.