Neoclassical synthesis

It was formulated most notably by John Hicks (1937),[2] Franco Modigliani (1944),[3] and Paul Samuelson (1948),[4] who dominated economics in the post-war period and formed the mainstream of macroeconomic thought in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s.

In the 1950s and 1960s, economists like Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow developed the neoclassical synthesis, which attempted to reconcile these two schools of thought.

The neoclassical synthesis emphasized the role of market forces in the economy, while also acknowledging the need for government intervention in certain circumstances.

Overall, the neoclassical synthesis was a significant development in the field of macroeconomics, as it brought together two previously competing schools of thought and created a more comprehensive theory of the economy.

The conditions of the period proved the impossibility of maintaining sustainable growth and low level of inflation via the measures suggested by the school.

[8][9][10] Several of these accounts, taken from Peter Howitt, N. Gregory Mankiw, and Michael Woodford's writings, are presented here for the reader's consideration: It seemed logical to regard Keynesian theory as relating to short-run fluctuations and general equilibrium theory as applying to long-run difficulties where adjustment problems could be safely neglected because wages were widely believed to be less than totally flexible in the short term.

[11] Since macroeconomics emerged as a distinct field of study, how to reconcile these two economic visions—one founded on Adam Smith's invisible hand and Alfred Marshall's supply and demand curves, the other on Keynes's analysis of an economy suffering from insufficient aggregate demand—has been a profound, nagging question.

Later, it was discovered that this association was caused by the fact that reduced unemployment rates drive increased nominal salaries, which are linked to rising prices since they represent the labor costs of the average business.

Thus, aggregate demand and the idea that it may temporarily lower unemployment at the expense of higher inflation prevailed in the Keynesian analysis framework.

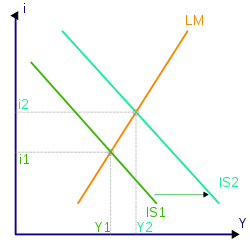

There was still a gap after the IS-LM-Phillips curve model became widely accepted as the unit of analysis in macroeconomic theory: putting numbers on variables like the marginal propensity to consume, the propensity to invest, or the sensitivity of money demand to interest rates, so that macroeconomic forecasts could be made or economic policy combinations could be simulated.

The work of Tobin (1969) is exceptional in the study of factors influencing investment because it popularized the "Q Theory" idea, which is based on the expected present value of future capital profits.

The person wants to maintain a steady level of consumption, therefore while he is young and has a low income, he typically borrows because he anticipates having larger wages during his productive era of life.

Paul Samuelson started the program of neoclassical synthesis, outlining two main objects of study: Much of neo-Keynesian economic theory was developed by leaders of economic profession, such as John Hicks, Maurice Allais, Franco Modigliani, Paul Samuelson, Alvin Hansen, Lawrence Klein, James Tobin and Don Patinkin.

[18] The process began soon after the publication of Keynes' General Theory with the IS-LM model (investment saving–liquidity preference money supply) first presented by John Hicks in a 1937 article.

But if monetary and fiscal policy is used to tackle underemployment, it will put the economy on a trajectory that applies the principles of classical equilibrium analysis to explain relative prices and resource allocation.

The interpretation of J. Keynes suggested by neoclassical synthesis economists is based on the mixture of basic features of general equilibrium theory with Keynesian concepts.

The development of the neoclassical synthesis started in 1937 with J. Hicks's publication of the paper Mr. Keynes and Classics, where he proposed the IS-LM scheme that has put the Keynesian theory into the more traditional terms of a simplified general equilibrium model with three markets: goods, money, and financial assets.

[26] P. Samuelson coined the term "neoclassical synthesis" in 1955[7] and put much effort into building and promoting the theory, in particular through his influential book Economics, first published in 1948.

[6] Through the 1950s, moderate degrees of government-led demand in industrial development and use of fiscal and monetary counter-cyclical policies continued and reached a peak in the "go go" 1960s, where it seemed to many neo-Keynesians that prosperity was now permanent.

This produced a "policy bind" and the collapse of the neoclassical-Keynesian consensus on the economy, leading to the development of new classical macroeconomics and new Keynesianism.

[29] Through the work of those such as S.Fischer (1977) and J.Taylor (1980), who demonstrated that the Philips curve can be replaced by a model of explicit nominal price and wage-setting with saving most of the traditional results,[6] these two schools would come together to create the new neoclassical synthesis that forms the basis of mainstream economics today.

In the short run, it may cause that some workers and industries will experience dislocation and hardship as a result of increased competition from foreign firms.

To minimalize these issues, the neoclassical synthesis suggests that governments could assist affected industries and workers with helpful policies.

The neoclassical synthesis has been called out in recent years by many scholars for not taking into consideration issues such as income inequality, environmental sustainability, and the distributional effects of globalization.

Research shows that the whole theory emphasis on efficiency gains may overlook these critical problems and scholars ask for more detailed and nuanced approach to understanding how globalization and trade truly works.

[34] In conclusion, the neoclassical synthesis argues that over time in a competitive labor market, wages and employment levels will simply adjust to reach their equilibrium.