Neural coding

[3] Neurons have an ability uncommon among the cells of the body to propagate signals rapidly over large distances by generating characteristic electrical pulses called action potentials: voltage spikes that can travel down axons.

[4] Although action potentials can vary somewhat in duration, amplitude and shape, they are typically treated as identical stereotyped events in neural coding studies.

In some neurons the strength with which a postsynaptic partner responds may depend solely on the 'firing rate', the average number of spikes per unit time (a 'rate code').

During recent years, more and more experimental evidence has suggested that a straightforward firing rate concept based on temporal averaging may be too simplistic to describe brain activity.

Temporal averaging can work well in cases where the stimulus is constant or slowly varying and does not require a fast reaction of the organism — and this is the situation usually encountered in experimental protocols.

The image projected onto the retinal photoreceptors changes therefore every few hundred milliseconds (Chapter 1.5 in [14]) Despite its shortcomings, the concept of a spike-count rate code is widely used not only in experiments, but also in models of neural networks.

There is a growing body of evidence that in Purkinje neurons, at least, information is not simply encoded in firing but also in the timing and duration of non-firing, quiescent periods.

[19] More generally, whenever a rapid response of an organism is required a firing rate defined as a spike-count over a few hundred milliseconds is simply too slow.

A further division by the interval length Δt yields time-dependent firing rate r(t) of the neuron, which is equivalent to the spike density of PSTH (Chapter 1.5 in [14]).

[14] Nevertheless, the experimental time-dependent firing rate measure can make sense, if there are large populations of independent neurons that receive the same stimulus.

[23] Temporal coding supplies an alternate explanation for the “noise," suggesting that it actually encodes information and affects neural processing.

In addition, responses are different enough between similar (but not identical) stimuli to suggest that the distinct patterns of spikes contain a higher volume of information than is possible to include in a rate code.

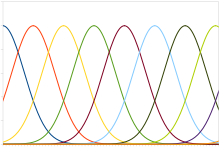

[3][6] One way in which temporal codes are decoded, in presence of neural oscillations, is that spikes occurring at specific phases of an oscillatory cycle are more effective in depolarizing the post-synaptic neuron.

This is not consistent with numerous organisms which are able to discriminate between stimuli in the time frame of milliseconds, suggesting that a rate code is not the only model at work.

[33] The mammalian gustatory system is useful for studying temporal coding because of its fairly distinct stimuli and the easily discernible responses of the organism.

[34] Temporally encoded information may help an organism discriminate between different tastants of the same category (sweet, bitter, sour, salty, umami) that elicit very similar responses in terms of spike count.

In studies dealing with the front cortical portion of the brain in primates, precise patterns with short time scales only a few milliseconds in length were found across small populations of neurons which correlated with certain information processing behaviors.

[25] As with the visual system, in mitral/tufted cells in the olfactory bulb of mice, first-spike latency relative to the start of a sniffing action seemed to encode much of the information about an odor.

Advances made in optogenetics allow neurologists to control spikes in individual neurons, offering electrical and spatial single-cell resolution.

[38] If neurons do encode information in individual spike timing patterns, key signals could be missed by attempting to crack the code while looking only at mean firing rates.

[24] Understanding any temporally encoded aspects of the neural code and replicating these sequences in neurons could allow for greater control and treatment of neurological disorders such as depression, schizophrenia, and Parkinson's disease.

Regulation of spike intervals in single cells more precisely controls brain activity than the addition of pharmacological agents intravenously.

A more sophisticated mathematical technique for performing such a reconstruction is the method of maximum likelihood based on a multivariate distribution of the neuronal responses.

Any individual neuron is too noisy to faithfully encode the variable using rate coding, but an entire population ensures greater fidelity and precision.

In contrast, when the tuning curves have multiple peaks, as in grid cells that represent space, the precision of the population can scale exponentially with the number of neurons.

Sparse coding of natural images produces wavelet-like oriented filters that resemble the receptive fields of simple cells in the visual cortex.

[63] The human primary visual cortex is estimated to be overcomplete by a factor of 500, so that, for example, a 14 x 14 patch of input (a 196-dimensional space) is coded by roughly 100,000 neurons.

[61] Other models are based on matching pursuit, a sparse approximation algorithm which finds the "best matching" projections of multidimensional data, and dictionary learning, a representation learning method which aims to find a sparse matrix representation of the input data in the form of a linear combination of basic elements as well as those basic elements themselves.

In the Drosophila olfactory system, sparse odor coding by the Kenyon cells of the mushroom body is thought to generate a large number of precisely addressable locations for the storage of odor-specific memories.

These results suggest that feedback inhibition suppresses Kenyon cell activity to maintain sparse, decorrelated odor coding and thus the odor-specificity of memories.