Development of the nervous system in humans

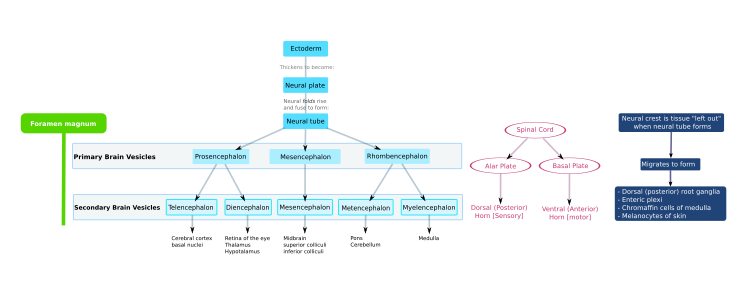

In the third week of human embryonic development the neuroectoderm appears and forms the neural plate along the dorsal side of the embryo.

[3] The CSF-filled central chamber is continuous from the telencephalon to the spinal cord, and constitutes the developing ventricular system of the CNS.

Because the neural tube gives rise to the brain and spinal cord any mutations at this stage in development can lead to fatal deformities like anencephaly or lifelong disabilities like spina bifida.

Synaptic communication between neurons leads to the establishment of functional neural circuits that mediate sensory and motor processing, and underlie behavior.

At the onset of gastrulation presumptive mesodermal cells move through the dorsal blastopore lip and form a layer in between the endoderm and the ectoderm.

During neural induction, noggin and chordin are produced by the dorsal mesoderm (notochord) and diffuse into the overlying ectoderm to inhibit the activity of BMP4.

Late in the fourth week, the superior part of the neural tube flexes at the level of the future midbrain—the mesencephalon.

The wall of the neural tube consists of neuroepithelial cells, which differentiate into neuroblasts, forming the mantle layer (the gray matter).

[8] Using structural MRI, quantitative assessment of a number of developmental processes can be carried out including defining growth patterns,[9] and characterizing the sequence of myelination.

[10] These data complement evidence from Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) studies that have been widely used to investigate the development of white matter.

[8] Higher resolution imaging has allowed three-dimensional ultrasound to help identify human brain development during the embryonic stages.

3D ultrasound imaging allows in-vivo depictions of ideal brain development which can help tp recognize irregularities during gestation.

[14] Subsequent waves of neurons split the preplate by migrating along radial glial fibres to form the cortical plate.

Each wave of migrating cells travel past their predecessors forming layers in an inside-out manner, meaning that the youngest neurons are the closest to the surface.

[18] An example of this mode of migration is in GnRH-expressing neurons, which make a long journey from their birthplace in the nose, through the forebrain, and into the hypothalamus.

Instead these multipolar cells express neuronal markers and extend multiple thin processes in various directions independently of the radial glial fibers.

They are distinguished from ubiquitous metabolites necessary for cellular maintenance and growth by their specificity; each neurotrophic factor promotes the survival of only certain kinds of neurons during a particular stage of their development.

In addition, it has been argued that neurotrophic factors are involved in many other aspects of neuronal development ranging from axonal guidance to regulation of neurotransmitter synthesis.

[28] Neurodevelopment in the adult nervous system includes mechanisms such as remyelination, generation of new neurons, glia, axons, myelin or synapses.

[41] In early development (before birth and during the first few months), the brain undergoes more changes in size, shape and structure than at any other time in life.

Improved understanding of cerebral development during this critical period is important for mapping normal growth, and for investigating mechanisms of injury associated with risk factors for maldevelopment such as premature birth.

Such spatio-temporal atlases can accurately represent the dynamic changes occurring during early brain development,[9] and can be used as a normative reference space.

Furthermore, large scale gene expression studies of different brain regions from early gestation to aging have been performed.

Interareal differences exhibit a temporal hourglass pattern, dividing human neocortical development into three major phases.

Then in late childhood and early adolescence, the genetic orchestra begins again and helps subtly shape neocortex regions that progressively perform more specialized tasks, a process that continues into adulthood.

In this region, more activity is noted in adolescents than in adults when faced with tests on mentalising tasks as well as communicative and personal intent.

[62] Early life stress is believed to produce changes in brain development by interfering with neurogenesis, synaptic production, and pruning of synapses and receptors.

Brain areas that undergo significant post-natal development, such as those involved in memory and emotion are more vulnerable to effects of early life stress.

Abnormalities in brain structure and function are often associated with deficits that may persist for years after the stress is removed, and may be a risk factor for future psychopathology.

Common types of early life stress that are documented include maltreatment, neglect, and previous institutionalization.