Neutral monism

As the philosopher David Chalmers has put it: "even when we have explained the performance of all the cognitive and behavioral functions in the vicinity of experience - perceptual discrimination, categorization, internal access, verbal report - there may still remain a further unanswered question: Why is the performance of these functions accompanied by experience?".

[2] With this, there has been growing demand for alternative ontologies (such as neutral monism) that may provide explanatory frameworks more suitable for explaining the existence of consciousness.

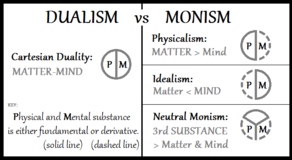

[4] Dualism is the view that reality is, broadly speaking, made up of two distinct substances or properties: physical substances/properties and mental substances/properties.

According to Baruch Spinoza, the mind and the body are dual aspects of Nature or God, which he identified as the only real substance.

[5] While schematic differences and neutral monism are quite stark, contemporary conceptions of the theories overlap in certain key areas.

For instance, Chalmers (1996) maintains that the difference between neutral monism and his preferred property dualism can, at times, be mostly semantic.

[11] H. H. Price argues that Hume's empiricism introduces a "neutral monist theory of sensation" as both "matter and mind are constructed out of sense-data".

[12][13] In the late 19th century, physicist Ernst Mach theorized that physical entities are nothing apart from their perceived mental properties.

[15] William James propounded the notion of radical empiricism to advance neutral monism in his essay "Does Consciousness Exist?"

[16] William James was one of the earliest philosophers to fully articulate a complete neutral monist view of the world.

Russell expressed interest in neutral monism early on his career, and officially endorsed the view from 1919 onward, at least until 1927, when The Analysis of Matter appeared.

The ontology of neutral monism conformed to the "supreme maxim in scientific philosophising", as Russell put it in "Logical Atomism" in 1924.

[18] His position was contentious among his contemporaries; G.E Moore maintained that Russell's philosophy was flawed due to a misinterpretation of facts (e.g. the concept of acquaintance).

Whately Carington in his book Matter, Mind, and Meaning (1949) advocated a form of neutral monism.

He considers Russell's solution of "protophenominal properties" to be ad hoc, and thinks such speculation undercuts the parsimony that made neutral monism initially appealing.

[note 2] As Chalmers puts it, a world of "pure causal flux" may be logically impossible, for there is "nothing for causation to relate.

This debate is integral to understanding neutral monism's approach to traditional concepts like “mind” and “matter.” Ernst Mach [38] exemplified this dilemma by proposing that entities such as "body" and "ego" are not fixed unities but rather provisional constructs or composites of more tightly interlinked elements.

Similarly, Bertrand Russell[39] advocated for the elimination of traditional psychological terms like "knowledge," "memory," "perception," and "sensation" from our vocabulary, as he believed they did not accurately represent the underlying reality.

Instead, Russell proposed neutral constructions to replace these entities, which, though devoid of traditional properties like solidity or inherent object-reference, were designed to fulfill similar roles.

[40] These properties, as basic, non-mental, and non-physical, are meant to underlie both mental and physical phenomena, thereby bridging the gap between mind and matter.

Additionally, Donovan Wishon [45] observes a later shift in Russell's work towards a materialistic ontology, indicating that the mental-physical distinction may be rooted more in our methods of knowledge acquisition than in intrinsic properties.

Although traditional neutral monists removed mentalistic connotations from sensations and experiences, the charge of mentalism remains a point of contention.

Critics like Chalmers and Strawson argue that neutral monism, like materialism, fails to accommodate experience, suggesting a gap between qualities and the awareness of them.

[48][49] Traditional neutral monists respond by arguing that appropriate relationships among qualities can lead to awareness, although the debate continues.

For instance, Landini suggests that Russell's later work implies a radical emergence of qualia, a position not universally accepted.