Nicolas Théobald

Nicolas Théobald, born in Montenach (Moselle) on August 31, 1903 and died in Obernai (Bas-Rhin) on May 10, 1981, was a Lorrain and French geologist, paleontologist and professor of geology at university of Besançon.

[1] He spent his entire childhood "rhythmic to the sound of bells";[2] he came from a family of eight children, his father being the mayor of the village, practicing husbandry and working in the fields.

His younger brother Albert, who accompanies him, finds one with six lines of text; translated by R. Clément, they reveal an account of the working hours of a worker in the tile factory.

In 1948, he participated in the founding of the University of Saarland, Universitas Saraviensis, where he was appointed as geology professor, and where he was elected Dean of the Faculty of Sciences (1949–1953).

[17] His basic works for the preparation for recruitment competitions for the teaching of earth sciences are based on a long practice of research in the field and in the laboratory, including his state thesis, "Les Insectes fossiles des terrains oligocènes de France", is the best-known testimony.

But, in the first half of the 20th century, most geologists and geographers believe that the tectonic movements responsible for the establishment of continents and mountains are no longer sensitive to the Quaternary era.

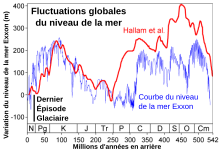

The modifications of the relief, when the continents are stable, are then linked to the variations in the level of the oceans, as explained by the eustatic theory, resulting from the work of the American geologist W.M.

During the glacial periods, water being capitalized in mountain glaciers and ice sheets, the sea level fell, which favored erosion in the lower course of the rivers, while their upper course was cluttered with fluvial-glacials debris.

At least four glacial periods have been listed in the Quaternary and the alternation of phases of digging and filling allowed the formation of stepped or nested terraces along the watercourses[22] (Pictures 1, 2 and 3).

The eustatic theory is justified in regions that have been stable since the end of the Tertiary era, such as large sedimentary basins, and Nicolas Théobald applied it in his first work on the Moselle valley downstream of Thionville; he recognizes terraces at 90, 60, 40 and 15 meters above the low water level of the river and relates them to the four great glacial periods of the Quaternary.

[26] (1912).,[27] Johannes Ernst Wilhelm Deecke (1917),[28] and A. Briquet (1928) .,[29] (1930).,[30] concludes like these geologists that, during the deposition of alluvium, the Haut-Rhin plain continued to sink (1933).

Then, in 1949, in his 'Contribution to the study of the lower Rhine terrace",[35] between Basel and Karlsruhe, N. Théobald concluded that "tectonic movements interfered with the backfilling phenomena linked to the eustatism of the base levels".

Indeed, the geologist seeking to date the sedimentary terrains on which he works, for example to establish a "geological map", is happy to find fossils and must identify them.

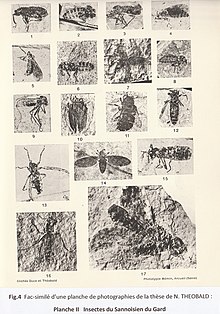

Benefiting from access to the collections of natural history museums, such as Basel, Marseille, Clermont-Ferrand, Brussels, the paleotonologist will analyze approximately 3,000 samples, which will be photographed, drawn, compared to already known fossil insects and to current representatives of the same genera, and determined (Picture 4)[note 1].

These fossils are divided into 650 species, including 300 new ones, which are replaced in their environment, by analyzing the conditions of sedimentation and plant remains: the biotopes are reconstituted, because the fauna characterizes the regional climates well.

In the south and south-east of our country, the Pyrenean orogeny having reached its paroxysmal stage and the Alps and Provence being in the process of uplift, trenches of collapses and synclines welcome the sedimentation of debris torn from the emerged lands: The coexistence of certain insects shows that, already between 25 and 35 million years before the present time, there are relations of commensalism or parasitism between the species; ants live in societies...

In an Additional Note on Oligocene fossil insects from the gypsums of Aix-en-Provence,[40] the paleontologist still describes new species, including a magnificent Lepidoptera of the Lycaenidae family, Aquisextana irenaei, dedicated to his wife Irene (Picture 5).

As part of his duties as a geologist associated with the BRGM for the development of geological maps, Nicolas Théobald was to ensure the search for drinking water for the communes of Haute-Saône; noting the risks of groundwater pollution by sandpits, metal processing workshops, slaughterhouses, dairies and landfills, he urged mayors to create security perimeters around drinking water catchments.

In a recent work, the mayor at the time, Pierre Bonnet, recalls the intervention of Professor Théobald of the University of Besançon, "scientist of reference for all geological studies",[55] who in 1970 wrote a report prior to the establishment of the lake.