Japanese language

There have been many attempts to group the Japonic languages with other families such as Ainu, Austronesian, Koreanic, and the now discredited Altaic, but none of these proposals have gained any widespread acceptance.

From the Heian period (794–1185), extensive waves of Sino-Japanese vocabulary entered the language, affecting the phonology of Early Middle Japanese.

Following the end of Japan's self-imposed isolation in 1853, the flow of loanwords from European languages increased significantly, and words from English roots have proliferated.

Japanese has a complex system of honorifics, with verb forms and vocabulary to indicate the relative status of the speaker, the listener, and persons mentioned.

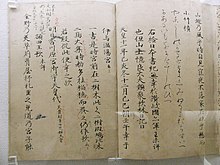

Texts written with Man'yōgana use two different sets of kanji for each of the morae now pronounced き (ki), ひ (hi), み (mi), け (ke), へ (he), め (me), こ (ko), そ (so), と (to), の (no), も (mo), よ (yo) and ろ (ro).

"hair of the eye"); modern mieru ("to be visible") and kikoeru ("to be audible") retain a mediopassive suffix -yu(ru) (kikoyu → kikoyuru (the attributive form, which slowly replaced the plain form starting in the late Heian period) → kikoeru (all verbs with the shimo-nidan conjugation pattern underwent this same shift in Early Modern Japanese)); and the genitive particle ga remains in intentionally archaic speech.

[31] Modern Japanese has become prevalent nationwide (including the Ryūkyū islands) due to education, mass media, and an increase in mobility within Japan, as well as economic integration.

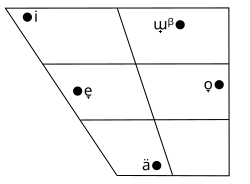

Japanese also includes a pitch accent, which is not represented in moraic writing; for example [haꜜ.ɕi] ("chopsticks") and [ha.ɕiꜜ] ("bridge") are both spelled はし (hashi), and are only differentiated by the tone contour.

Chinese characters were also used to write grammatical elements; these were simplified, and eventually became two moraic scripts: hiragana and katakana which were developed based on Manyogana.

Historically, attempts to limit the number of kanji in use commenced in the mid-19th century, but government did not intervene until after Japan's defeat in the Second World War.

During the post-war occupation (and influenced by the views of some U.S. officials), various schemes including the complete abolition of kanji and exclusive use of rōmaji were considered.

Under popular pressure and following a court decision holding the exclusion of common characters unlawful, the list of jinmeiyō kanji was substantially extended from 92 in 1951 (the year it was first decreed) to 983 in 2004.

Unlike many Indo-European languages, the only strict rule of word order is that the verb must be placed at the end of a sentence (possibly followed by sentence-end particles).

That said, if the subject is clearly a subtopic, this differentiation effect may or may not be relevant, such as in nihongo wa bunpo ga yasashii (日本語は文法が優しい).

Such beneficiary auxiliary verbs thus serve a function comparable to that of pronouns and prepositions in Indo-European languages to indicate the actor and the recipient of an action.

(grammatically correct) This is partly because these words evolved from regular nouns, such as kimi "you" (君 "lord"), anata "you" (あなた "that side, yonder"), and boku "I" (僕 "servant").

The choice of words used as pronouns is correlated with the sex of the speaker and the social situation in which they are spoken: men and women alike in a formal situation generally refer to themselves as watashi (私, literally "private") or watakushi (also 私, hyper-polite form), while men in rougher or intimate conversation are much more likely to use the word ore (俺 "oneself", "myself") or boku.

Where number is important, it can be indicated by providing a quantity (often with a counter word) or (rarely) by adding a suffix, or sometimes by duplication (e.g. 人人, hitobito, usually written with an iteration mark as 人々).

For verbs that represent an ongoing process, the -te iru form indicates a continuous (or progressive) aspect, similar to the suffix ing in English.

Some simple queries are formed simply by mentioning the topic with an interrogative intonation to call for the hearer's attention: Kore wa?

These include for example: Note: The subtle difference between wa and ga in Japanese cannot be derived from the English language as such, because the distinction between sentence topic and subject is not made there.

The differences in social position are determined by a variety of factors including job, age, experience, or even psychological state (e.g., a person asking a favour tends to do so politely).

There are three main sources of words in the Japanese language: the yamato kotoba (大和言葉) or wago (和語); kango (漢語); and gairaigo (外来語).

Tonakai (reindeer), rakko (sea otter) and shishamo (smelt, a type of fish) are well-known examples of words of Ainu origin.

Incorporating vocabulary from European languages, gairaigo, began with borrowings from Portuguese in the 16th century, followed by words from Dutch during Japan's long isolation of the Edo period.

Words such as wanpatān ワンパターン (< one + pattern, "to be in a rut", "to have a one-track mind") and sukinshippu スキンシップ (< skin + -ship, "physical contact"), although coined by compounding English roots, are nonsensical in most non-Japanese contexts; exceptions exist in nearby languages such as Korean however, which often use words such as skinship and rimokon (remote control) in the same way as in Japanese.

[57] Joseigo and danseigo are different in various ways, including first-person pronouns (such as watashi or atashi 私 for women and boku (僕) for men) and sentence-final particles (such as wa (わ), na no (なの), or kashira (かしら) for joseigo, or zo (ぞ), da (だ), or yo (よ) for danseigo).

[56] In the 1990s, the traditional feminine speech patterns and stereotyped behaviors were challenged, and a popular culture of “naughty” teenage girls emerged, called kogyaru (コギャル), sometimes referenced in English-language materials as “kogal”.

[58] Their rebellious behaviors, deviant language usage, the particular make-up called ganguro (ガングロ), and the fashion became objects of focus in the mainstream media.

Ningen wa, risei to ryōshin to o sazukerarete ori, tagai ni dōhō no seishin o motte kōdō shinakereba naranai.All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.