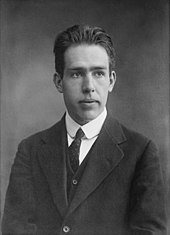

Niels Bohr

Niels Henrik David Bohr (7 October 1885 – 18 November 1962) was a Danish theoretical physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum theory, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922.

He conceived the principle of complementarity: that items could be separately analysed in terms of contradictory properties, like behaving as a wave or a stream of particles.

Bohr mentored and collaborated with physicists including Hans Kramers, Oskar Klein, George de Hevesy, and Werner Heisenberg.

[6][7] In 1905 a gold medal competition was sponsored by the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters to investigate a method for measuring the surface tension of liquids that had been proposed by Lord Rayleigh in 1879.

He went beyond the original task, incorporating improvements into both Rayleigh's theory and his method, by taking into account the viscosity of the water, and by working with finite amplitudes instead of just infinitesimal ones.

He surveyed the literature on the subject, settling on a model postulated by Paul Drude and elaborated by Hendrik Lorentz, in which the electrons in a metal are considered to behave like a gas.

Bohr extended Lorentz's model, but was still unable to account for phenomena like the Hall effect, and concluded that electron theory could not fully explain the magnetic properties of metals.

[44] Many older physicists, like Thomson, Rayleigh and Hendrik Lorentz, did not like the trilogy, but the younger generation, including Rutherford, David Hilbert, Albert Einstein, Enrico Fermi, Max Born and Arnold Sommerfeld saw it as a breakthrough.

The First World War broke out while they were in Tyrol, greatly complicating the trip back to Denmark and Bohr's subsequent voyage with Margrethe to England, where he arrived in October 1914.

[52][53] Bohr's institute served as a focal point for researchers into quantum mechanics and related subjects in the 1920s and 1930s, when most of the world's best-known theoretical physicists spent some time in his company.

Early arrivals included Hans Kramers from the Netherlands, Oskar Klein from Sweden, George de Hevesy from Hungary, Wojciech Rubinowicz from Poland, and Svein Rosseland from Norway.

[73] He conceived the philosophical principle of complementarity: that items could have apparently mutually exclusive properties, such as being a wave or a stream of particles, depending on the experimental framework.

In a paper presented at the Como Conference in September 1927, Bohr emphasised that Heisenberg's uncertainty relations could be derived from classical considerations about the resolving power of optical instruments.

[80] By 1929 the phenomenon of beta decay prompted Bohr to again suggest that the law of conservation of energy be abandoned, but Enrico Fermi's hypothetical neutrino and the subsequent 1932 discovery of the neutron provided another explanation.

[81][82] The discovery of nuclear fission by Otto Hahn in December 1938 (and its theoretical explanation by Lise Meitner) generated intense interest among physicists.

"[84] Based on his liquid drop model of the nucleus, Bohr concluded that it was the uranium-235 isotope and not the more abundant uranium-238 that was primarily responsible for fission with thermal neutrons.

The argument is simply that by the word 'experiment' we refer to a situation where we can tell to others what we have done and what we have learned and that, therefore, the account of the experimental arrangement and of the results of the observations must be expressed in unambiguous language with suitable application of the terminology of classical physics (APHK, p.

Faye groups explanations into five frameworks: empiricism (i.e. logical positivism); Kantianism (or Neo-Kantian models of epistemology); Pragmatism (which focus on how human beings experientially interact with atomic systems according to their needs and interests); Darwinianism (i.e. we are adapted to use classical type concepts, which Léon Rosenfeld said that we evolved to use); and Experimentalism (which focuses strictly on the function and outcome of experiments that thus must be described classically).

[100] To prevent the Germans from discovering Max von Laue's and James Franck's gold Nobel medals, Bohr had de Hevesy dissolve them in aqua regia.

[104] Bohr was aware of the possibility of using uranium-235 to construct an atomic bomb, referring to it in lectures in Britain and Denmark shortly before and after the war started, but he did not believe that it was technically feasible to extract a sufficient quantity of uranium-235.

[106] Ivan Supek, one of Heisenberg's students and friends, claimed that the main subject of the meeting was Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker, who had proposed trying to persuade Bohr to mediate peace between Britain and Germany.

With the subsequent release of Bohr's letters, the play has been criticised by historians as being a "grotesque oversimplification and perversion of the actual moral balance" due to adopting a pro-Heisenberg perspective.

Bohr, equipped with parachute, flying suit and oxygen mask, spent the three-hour flight lying on a mattress in the aircraft's bomb bay.

[125] During the flight, Bohr did not wear his flying helmet as it was too small, and consequently did not hear the pilot's intercom instruction to turn on his oxygen supply when the aircraft climbed to high altitude to overfly Norway.

He visited Einstein and Pauli at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, and went to Los Alamos in New Mexico, where the nuclear weapons were being designed.

[133] In May 1944 the Danish resistance newspaper De frie Danske reported that they had learned that 'the famous son of Denmark Professor Niels Bohr' in October the previous year had fled his country via Sweden to London and from there travelled to Moscow from where he could be assumed to support the war effort.

[138] Churchill disagreed with the idea of openness towards the Russians to the point that he wrote in a letter: "It seems to me Bohr ought to be confined or at any rate made to see that he is very near the edge of mortal crimes.

"[139] Oppenheimer suggested that Bohr visit President Franklin D. Roosevelt to convince him that the Manhattan Project should be shared with the Soviets in the hope of speeding up its results.

[150][151] Bohr designed his own coat of arms, which featured a taijitu (symbol of yin and yang) and a motto in Latin: contraria sunt complementa, "opposites are complementary".

[158] He was cremated, and his ashes were buried in the family plot in the Assistens Cemetery in the Nørrebro section of Copenhagen, along with those of his parents, his brother Harald, and his son Christian.