Nitrogen cycle

Many of those processes are carried out by microbes, either in their effort to harvest energy or to accumulate nitrogen in a form needed for their growth.

For example, the nitrogenous wastes in animal urine are broken down by nitrifying bacteria in the soil to be used by plants.

Between 5 and 10 billion kg per year are fixed by lightning strikes, but most fixation is done by free-living or symbiotic bacteria known as diazotrophs.

Most biological nitrogen fixation occurs by the activity of molybdenum (Mo)-nitrogenase, found in a wide variety of bacteria and some Archaea.

Symbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacteria such as Rhizobium usually live in the root nodules of legumes (such as peas, alfalfa, and locust trees).

In plants that have a symbiotic relationship with rhizobia, some nitrogen is assimilated in the form of ammonium ions directly from the nodules.

[26] Bacteria and fungi convert this organic nitrogen into ammonia through a series of processes called ammonification or mineralization.

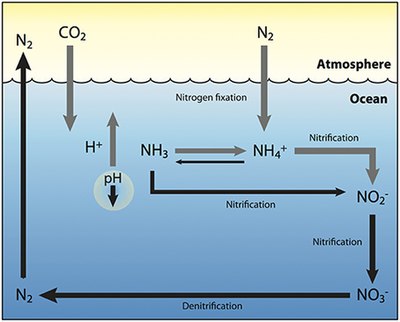

In the primary stage of nitrification, the oxidation of ammonium (NH+4) is performed by bacteria such as the Nitrosomonas species, which converts ammonia to nitrites (NO−2).

This is occurring along the same lines as control of phosphorus fertilizer, restriction of which is normally considered essential to the recovery of eutrophied waterbodies.

The denitrifying bacteria use nitrates in the soil to carry out respiration and consequently produce nitrogen gas, which is inert and unavailable to plants.

Microbes which undertake DNRA oxidise organic matter and use nitrate as an electron acceptor, reducing it to nitrite, then ammonium (NO−3 → NO−2 → NH+4).

[44] Phytoplankton need nitrogen in biologically available forms for the initial synthesis of organic matter.

Ammonium is thought to be the preferred source of fixed nitrogen for phytoplankton because its assimilation does not involve a redox reaction and therefore requires little energy.

One reason is that only continual input of new nitrogen can determine the total capacity of the ocean to produce a sustainable fish harvest.

[41] As a result of extensive cultivation of legumes (particularly soy, alfalfa, and clover), growing use of the Haber–Bosch process in the production of chemical fertilizers, and pollution emitted by vehicles and industrial plants, human beings have more than doubled the annual transfer of nitrogen into biologically available forms.

[30] In addition, humans have significantly contributed to the transfer of nitrogen trace gases from Earth to the atmosphere and from the land to aquatic systems.

Human alterations to the global nitrogen cycle are most intense in developed countries and in Asia, where vehicle emissions and industrial agriculture are highest.

[48] Generation of Nr, reactive nitrogen, has increased over 10 fold in the past century due to global industrialisation.

[50] Nitrous oxide (N2O) has risen in the atmosphere as a result of agricultural fertilization, biomass burning, cattle and feedlots, and industrial sources.

Nitrous oxide is also a greenhouse gas and is currently the third largest contributor to global warming, after carbon dioxide and methane.

While not as abundant in the atmosphere as carbon dioxide, it is, for an equivalent mass, nearly 300 times more potent in its ability to warm the planet.

They are precursors of tropospheric (lower atmosphere) ozone production, which contributes to smog and acid rain, damages plants and increases nitrogen inputs to ecosystems.

[30] Decreases in biodiversity can also result if higher nitrogen availability increases nitrogen-demanding grasses, causing a degradation of nitrogen-poor, species-diverse heathlands.

[53] Increasing levels of nitrogen deposition is shown to have several adverse effects on both terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems.

Due to the ongoing changes caused by high nitrogen deposition, an environment's susceptibility to ecological stress and disturbance – such as pests and pathogens – may increase, thus making it less resilient to situations that otherwise would have little impact on its long-term vitality.

[57] Eutrophication often leads to lower dissolved oxygen levels in the water column, including hypoxic and anoxic conditions, which can cause death of aquatic fauna.

Relatively sessile benthos, or bottom-dwelling creatures, are particularly vulnerable because of their lack of mobility, though large fish kills are not uncommon.

Oceanic dead zones near the mouth of the Mississippi in the Gulf of Mexico are a well-known example of algal bloom-induced hypoxia.

[58][59] The New York Adirondack Lakes, Catskills, Hudson Highlands, Rensselaer Plateau and parts of Long Island display the impact of nitric acid rain deposition, resulting in the killing of fish and many other aquatic species.

Some other non-point sources for nitrate pollution in groundwater originate from livestock feeding, animal and human contamination, and municipal and industrial waste.

2 fixation (red), nitrification (light blue), nitrate reduction (violet), DNRA (magenta), denitrification (aquamarine), N-damo (green), and anammox (orange). Black curved arrows represent physical processes such as advection and diffusion. [ 40 ]