Old Norse religion

Transmitted through oral culture rather than through codified texts, Old Norse religion focused heavily on ritual practice, with kings and chiefs playing a central role in carrying out public acts of sacrifice.

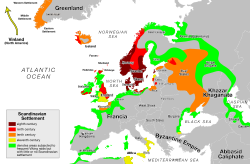

[25] During this period, the Norse interacted closely with other ethnocultural and linguistic groups, such as the Sámi, Balto-Finns, Anglo-Saxons, Greenlandic Inuit, and various speakers of Celtic and Slavic languages.

[28] In Hilda Ellis Davidson's words, present-day knowledge of Old Norse religion contains "vast gaps", and we must be cautious and avoid "bas[ing] wild assumptions on isolated details".

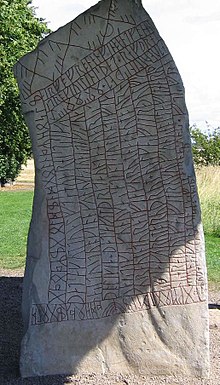

[31] In contrast to the few runic fragments, a considerable body of literary and historical sources survive in Old Norse manuscripts using the Latin script, all of which were created after the Christianisation of Scandinavia, the majority in Iceland.

[37] One important written source is Snorri's Prose Edda, which incorporates a manual of Norse mythology for the use of poets in constructing kennings; it also includes numerous citations, some of them the only record of lost poems,[38] such as Þjóðólfr of Hvinir's Haustlöng.

The first non-Scandinavian textual source for the Old Norse Religion was Tacitus' book, the Germania, which dates back to around 100 CE[40] and describes religious practices of several Germanic peoples, but has little coverage of Scandinavia.

[46][47] Many aspects of material culture—including settlement locations, artefacts and buildings—may cast light on beliefs, and archaeological evidence regarding religious practices indicates chronological, geographic and class differences far greater than are suggested by the surviving texts.

[66] Unlike other Nordic societies, Iceland lacked a monarchy and thus a centralising authority which could enforce religious adherence;[67] there were both Old Norse and Christian communities from the time of its first settlement.

[69] Several British place-names indicate possible religious sites;[70] for instance, Roseberry Topping in North Yorkshire was known as Othensberg in the twelfth century, a name deriving from the Old Norse Óðinsberg ("Hill of Óðin").

On returning to Norway, he kept his faith largely private but encouraged Christian priests to preach among the population; some pagans were angered and—according to Heimskringla—three churches built near Trondheim were burned down.

[89] In an attempt to preserve unity, at the Althing in 999, an agreement was reached that the Icelandic law would be based on Christian principles, albeit with concessions to the pagan community.

[118][119] There are also accounts in sagas of individuals who devoted themselves to a single deity,[120] described as a fulltrúi or vinr (confidant, friend) as seen in Egill Skallagrímsson's reference to his relationship with Odin in his "Sonatorrek", a tenth-century skaldic poem for example.

[147] A different account is provided in Vafþrúðnismál, which describes that the world is made from the components of Ymir's body: the earth from his flesh, the mountains from his bones, the sky from his skull, and the sea from his blood.

[183] In addition to seasonal festivals, an animal blót could take place, for example, before duels, after the conclusion of business between traders, before sailing to ensure favourable winds, and at funerals.

[196] Mentions of people being "sentenced to sacrifice" and of the "wrath of the gods" against criminals suggest a sacral meaning for the death penalty;[197] in Landnamabók the method of execution is given as having the back broken on a rock.

[208] This practice extended to non-Scandinavian areas inhabited by Norse people; for example in Britain, a sword, tools, and the bones of cattle, horses and dogs were deposited under a jetty or bridge over the River Hull.

[226] In certain areas of the Nordic world, namely coastal Norway and the Atlantic colonies, smaller boat burials are sufficiently common to indicate it was no longer only an elite custom.

A passage in Snorri Sturluson's Ynglinga Saga states that Odin—whom he presents as a human king later mistaken for a deity—instituted laws that the dead would be burned on a pyre with their possessions, and burial mounds or memorial stones erected for the most notable men.

[228][229] Also in his Prose Edda, the god Baldr is burned on a pyre on his ship, Hringhorni, which is launched out to sea with the aid of the gýgr Hyrrokkin; Snorri wrote after the Christianisation of Iceland, but drew on Úlfr Uggason's skaldic poem "Húsdrápa".

[230] The myth preserved in the Eddic poem "Hávamál" of Odin hanging for nine nights on Yggdrasill, sacrificing himself to secure knowledge of the runes and other wisdom in what resembles an initiatory rite,[231][232] is evidence of mysticism in Old Norse religion.

[255] Place-name evidence suggests that cultic practices might also take place at many different kinds of sites, including fields and meadows (vangr, vin), rivers, lakes and bogs, groves (lundr) and individual trees, and rocks.

[263] Adam of Bremen's 11th-century Latin history describes at length a great temple at Uppsala at which human sacrifices regularly took place, and containing statues of Thor, Wotan and Frikko (presumably Freyr); a scholion adds the detail that a golden chain hung from the eaves.

In 1966, based on the results of a comprehensive archaeological survey of most of Scandinavia, the Danish archaeologist Olaf Olsen proposed the model of the "temple farm": that rather than the hof being a dedicated building, a large longhouse, especially that of the most prominent farmer in the district, served as the location for community cultic celebrations when required.

[278] In medieval Iceland, the goði was a social role that combined religious, political, and judicial functions,[278] responsible for serving as a chieftain in the district, negotiating legal disputes, and maintaining order among his þingmenn.

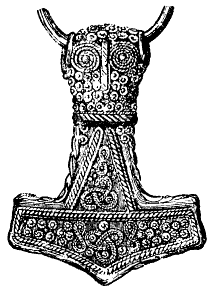

[287] The two religious symbols may have co-existed closely; one piece of archaeological evidence suggesting that this is the case is a soapstone mould for casting pendants discovered from Trengården in Denmark.

[292] A bronze figurine from Rällinge in Södermanland has been attributed to Freyr because it has a big phallus, and a silver pendant from Aska in Östergötland has been seen as Freya because it wears a necklace that could be Brisingamen.

As a result, artists featured Norse gods and goddesses in their paintings and sculptures, and their names were applied to streets, squares, journals, and companies throughout parts of northern Europe.

[295] The mythological stories derived from Old Norse and other Germanic sources inspired various artists, including Richard Wagner, who used these narratives as the basis for his Der Ring des Nibelungen.

[296] Theories about a shamanic component of Old Norse religion have been adopted by forms of Nordic neoshamanism; groups practising what they called seiðr was established in Europe and the United States by the 1990s.

[295] Since this research appeared from the background of European romanticism, many of the scholars operating in the 19th and 20th centuries framed their approach through nationalism, and were strongly influenced by their interpretations by romantic notions about nationhood, conquest, and religion.