Offshore wind power

[16] A 2013 review of the engineering aspects of turbines like the sizes used onshore, including the electrical connections and converters, considered that the industry had in general been overoptimistic about the benefits-to-costs ratio and concluded that the "offshore wind market doesn’t look as if it is going to be big".

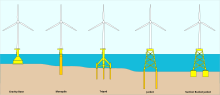

[21][22] The history of the development of wind farms in the North Sea, as regards the United Kingdom, indicates three phases: coastal, off-coastal and deep offshore in the period 2004 through to 2021.

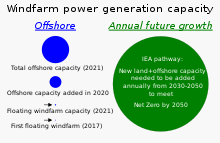

[45] The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) predicted in 2016 that offshore wind power will grow to 8% of ocean economy by 2030, and that its industry will employ 435,000 people, adding $230 billion of value.

Since 2003, the EIB has sponsored 34 offshore wind projects in Europe, including facilities in Belgium, Denmark, Germany, France, the Netherlands, Portugal, and the United Kingdom, totaling more over €10 billion in loans.

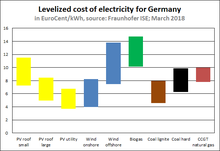

Economics of offshore wind farms tend to favor larger turbines, as installation and grid connection costs decrease per unit energy produced.

These cost estimates are based on projections that anticipate a ninefold increase in global offshore wind energy deployment, supported by advancements in infrastructure such as supply chains, ports, and transmission systems.

[65][66] Offshore wind resources are by their nature both huge in scale and highly dispersed, considering the ratio of the planet's surface area that is covered by oceans and seas compared to land mass.

Wind speeds offshore are known to be considerably higher than for the equivalent location onshore due to the absence of land mass obstacles and the lower surface roughness of water compared to land features such as forests and savannah, a fact that is illustrated by global wind speed maps that cover both onshore and offshore areas using the same input data and methodology.

These include: Existing hardware for measurements includes Light Detection and Ranging (LIDAR), Sonic Detection and Ranging (SODAR), radar, autonomous underwater vehicles (AUV), and remote satellite sensing, although these technologies should be assessed and refined, according to a report from a coalition of researchers from universities, industry, and government, supported by the Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future.

[80][81] In Denmark, many of these phases have been deliberately streamlined by authorities in order to minimize hurdles,[82] and this policy has been extended for coastal wind farms with a concept called ’one-stop-shop’.

The relevant international legal framework is UNCLOS (United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea) which regulates the rights and responsibilities of the States in regard to the use of the oceans.

In the territorial waters (up to 12 nautical miles from the baseline of the coast) the coastal State has full sovereignty[85] and therefore, the regulation of offshore wind turbines are fully under national jurisdiction.

[85] Within this zone the purpose of producing energy is not explicitly mentioned as a high seas freedom, and the legal status of offshore wind facilities is therefore unclear.

[86] As a solution, it has been suggested that offshore wind facilities could be incorporated as a high seas freedom by being considered as ships or artificial islands, installations and structures.

The displayed map of Vietnam provides an estimate of technical potential for that country for both fixed foundation and floating offshore wind turbines according to the water depth.

As the first offshore wind farms reach their end of life, a demolition industry develops to recycle them at a cost of DKK 2-4 million ($300,000-600,000 USD) roughly per MW, to be guaranteed by the owner.

[123] Offshore wind provider Vattenfall declared a fifteen million pound investment package into the local area of Norfolk in order to support climate change based projects.

[124] As the offshore wind industry has evolved and expanded on a rapid scale, a number of European Directives have been created concerning the necessary environmental considerations that must be taken into account by developers.

[125] The EIA was implemented as a means of preventing further disturbance towards aspects including marine organisms, the seabed and the ecosystem as a whole that are generated from critical infrastructure such as offshore wind installations.

[126] If the development of an offshore wind infrastructure fails to comply with the measures associated with an EIA, the operator is obliged to compensate the environment in another aspect in order to nullify the damage it may create.

[129] However, as the capacity of offshore wind has increased, a developing domain of academic research has continuously looked into a range of environmental side effects during the turbine life cycle phases of construction, operations and decommissioning.

The installation and deinstallation as well as the required maintenance of offshore wind structures have the potential to produce substantially negative environmental impacts towards the marine environment.

The timing of such processes is key since it has been found that the presence of these activities during periods of migration and reproduction can have disruptive impacts towards marine wildlife such as seabirds and fish.

[131] In addition, the installation of offshore wind infrastructure has been claimed to be a key impactor in the displacement of marine wildlife such as seabirds, however the available published work on this matter is limited.

[135] The welfare of seabirds is at risk due to the potential for collisions with the turbines, as well as causing the birds to adjust their travel routes which can significantly impact their endurance as a migratory specie.

[143] As the offshore wind industry has developed, a range of environmental considerations have come to the fore concerning the spatial planning decision processes of the turbines.

In 2022, the Scottish government published a study outlining a mathematical formula for its own collision risk model which calculated the potential for seabirds to collide into wind turbines.

[148] However, as marine spatial planning offers a common legal framework, it has been claimed to be an overall benefit for environmental considerations to be realised in relation to offshore wind developments.

[150] Given the expected increase in number and geographical distribution of windfarms in the coming years, more effective measures are needed to cover security blind spots, including those below the waterline.

[154] In addition, a large proportion of critical parts for constructing and maintaining maritime wind and solar infrastructure is manufactured outside of the EU/NATO states, which potentially represents a supply chain risk.