Old East Slavic

[25] American Slavist Alexander M. Schenker pointed out that modern terms for the medieval language of the East Slavs varied depending on the political context.

Therefore, today we may speak definitively only of the languages of surviving manuscripts, which, according to some interpretations, show regional divergence from the beginning of the historical records.

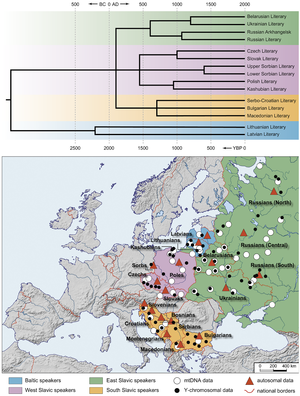

[46][47][48] The political unification of the region into the state called Kievan Rus', from which modern Belarus, Russia and Ukraine trace their origins, occurred approximately a century before the adoption of Christianity in 988 and the establishment of the South Slavic Old Church Slavonic as the liturgical and literary language.

Despite some suggestive archaeological finds and a corroboration by the tenth-century monk Chernorizets Hrabar that ancient Slavs wrote in "strokes and incisions", the exact nature of this system is unknown.

[49][citation needed] The samples of birch-bark writing excavated in Novgorod have provided crucial information about the pure tenth-century vernacular in North-West Russia, almost entirely free of Church Slavonic influence.

In this usage example of the language, the fall of the yers is in progress or arguably complete: several words end with a consonant, e.g. кнѧжит, knęžit "to rule" < кънѧжити, kǔnęžiti (modern Uk княжити, knjažyty, R княжить, knjažit', B княжыць, knjažyc').

South Slavic features include времѧньнъıх, vremęnǐnyx "bygone" (modern R минувших, minuvšix, Uk минулих, mynulyx, B мінулых, minulyx).

Correct use of perfect and aorist: єсть пошла, estǐ pošla "is/has come" (modern B пайшла, pajšla, R пошла, pošla, Uk пішла, pišla), нача, nača "began" (modern Uk почав, počav, B пачаў, pačaŭ, R начал, načal) as a development of the old perfect.

It has been suggested that the phrase растекаться мыслью по древу (rastekat'sja mysl'ju po drevu, to run in thought upon/over wood), which has become proverbial in modern Russian with the meaning "to speak ornately, at length, excessively," is a misreading of an original мысію, mysiju (akin to мышь "mouse") from "run like a squirrel/mouse on a tree"; however, the reading мыслью, myslǐju is present in both the manuscript copy of 1790 and the first edition of 1800, and in all subsequent scholarly editions.

Other 11th-century writers are Theodosius, a monk of the Kiev Pechersk Lavra, who wrote on the Latin faith and some Pouchenia or Instructions, and Luka Zhidiata, bishop of Novgorod, who has left a curious Discourse to the Brethren.

In the 12th century, we have the sermons of bishop Cyril of Turov, which are attempts to imitate in Old East Slavic the florid Byzantine style.

In his sermon on Holy Week, Christianity is represented under the form of spring, Paganism and Judaism under that of winter, and evil thoughts are spoken of as boisterous winds.

There are also the works of early travellers, as the igumen Daniel, who visited the Holy Land at the end of the eleventh and beginning of the twelfth century.

This composition is generally found inserted in the Chronicle of Nestor; it gives a fine picture of the daily life of a Slavonic prince.

The Paterik of the Kievan Caves Monastery is a typical medieval collection of stories from the life of monks, featuring devils, angels, ghosts, and miraculous resurrections.

The Zadonshchina is a sort of prose poem much in the style of the Tale of Igor's Campaign, and the resemblance of the latter to this piece furnishes an additional proof of its genuineness.

The early laws of Rus' present many features of interest, such as the Russkaya Pravda of Yaroslav the Wise, which is preserved in the chronicle of Novgorod; the date is between 1018 and 1072.

The earliest attempts to compile a comprehensive lexicon of Old East Slavic were undertaken by Alexander Vostokov and Izmail Sreznevsky in the nineteenth century.